TV shows like Dangerous Jobs, Deadliest Job Interview, Ax Men, and Deadliest Catch vividly portray some of the most dangerous jobs people have. Here at the Bureau of Labor Statistics we produce data about dangers in the workplace, or workplace injuries, illnesses, and fatalities.

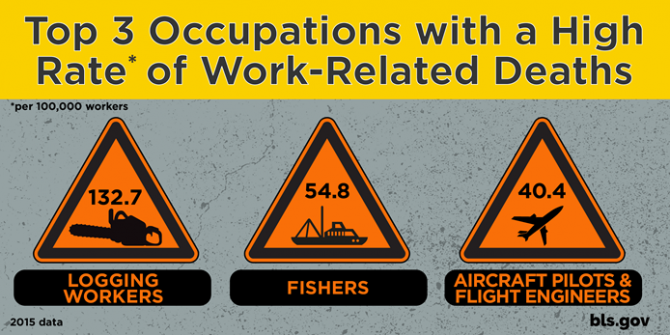

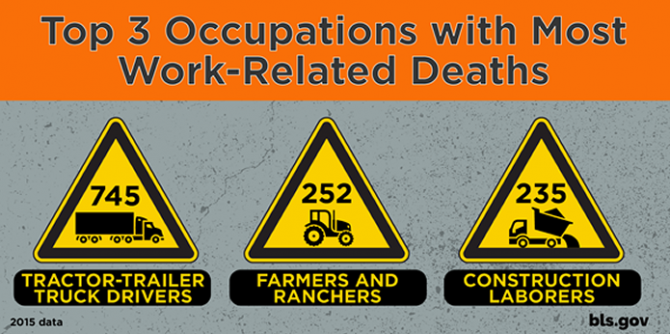

Our list of occupations with high fatal injury rates (on page 19) is often used externally as a list of the “most dangerous” jobs. However, at BLS we strongly believe there is no one measure that tells which job is the most dangerous. Why is that?

For starters, there is no universal definition of “dangerous” or “hazardous.” There are many other elements that factor into any definition of a “dangerous job,” such as the likelihood of incurring a nonfatal injury, the potential severity of that nonfatal injury, the safety precautions necessary to perform the job, and the physical and mental demands of the job.

It’s also difficult to accurately measure fatal injury rates for occupations with fewer workers.

BLS has certain minimum thresholds that must be met for a fatal injury rate to be published. So, fatal injury rates are not calculated for many occupations that have a relatively small number of fatal work injuries and employment.

Take the occupation elephant trainer*, for instance. Because few workers are employed as elephant trainers, a small number of fatal injuries to elephant trainers would make the fatal injury rate extremely high for a single year, despite their low number of deaths. On the other hand, in most years, this occupation incurs no deaths, rendering their fatality rate 0 and ranking them among the least at risk for incurring a fatal injury.

BLS provides the data to help people, from policymakers to businesses and workers, better understand hazards in the workplace. However, we can only talk about what our data show, such as the number of deaths and fatal injury rates of different occupations. We have to leave it to others to analyze or rank the danger of particular jobs.

*“Elephant trainer” is a hypothetical occupational classification. The classification BLS uses groups these workers with either “artists and performers” or “animal caretakers,” both of which include many more people than just elephant trainers.

United States Department of Labor

United States Department of Labor