The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics is best known for our monthly job and inflation reports. We also publish data on many other topics, ranging from how Americans spend their time and money to workplace injuries and the growth of entrepreneurship. My blog series, “Why This Counts,” explains why we conduct our surveys and how people can use the data at work and home. I hope this series will take the mystery out of our data and make our work come to life for both new and advanced users.

Today I want to tell you about a fascinating group of surveys called the National Longitudinal Surveys. It’s especially timely to talk about these surveys for two reasons: 1) we published a news release this week with the latest data from one of the surveys, and 2) the program is one of the important legacies of former BLS Commissioner Janet Norwood, who passed away recently.

The National Longitudinal Surveys stand out because they are designed to answer key long-term questions about people’s paths through life. Most of our measures about the labor market and economy focus on current conditions. What’s the national unemployment rate? How rapidly is employment growing in California or North Dakota or Georgia? How many job openings are there in manufacturing? What are the trends in consumer prices for food, energy, clothing, and shelter? It’s important to have up-to-date answers for these and other economic questions. But some questions take longer to answer—years or even decades.

Some long-term questions we care about include: How many jobs do people hold over their lifetimes? How do earnings grow at different stages of workers’ careers? The surveys designed to answer these and other long-term questions are called “longitudinal” surveys. What’s that mean?

A longitudinal survey asks questions about the same people at different points in their lives. Longitudinal surveys are useful for studying changes that occur over long periods. These surveys are also useful for examining cause-and-effect relationships. For example, how do events that happened when a person was in high school affect labor market success as an adult? This week we published a new report that looks at the experiences of baby boomers from age 18 to age 48.

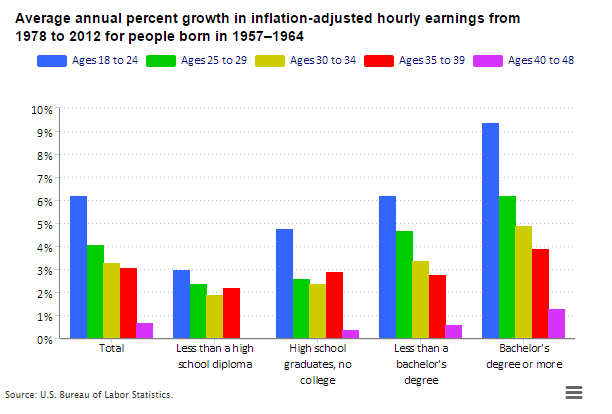

The survey follows a set of people born in the latter years of the post-World War II baby boom, 1957 to 1964, and living in the United States when the survey began in 1979. To answer my earlier questions—using just-released data—these baby boomers held an average of 11.7 jobs from age 18 to age 48. Their inflation-adjusted hourly earnings grew the most during their late teens and early twenties, and earnings generally grew faster for college graduates than for people with less education.

The survey doesn’t just ask about labor market activity. It also asks about education, training, health, marriages and other relationships, children, use of government programs, juvenile crimes and arrests, drug and alcohol use, and much more. Why do we ask about these topics, some of which are pretty sensitive? In short, we’re trying to understand all the things that affect or are affected by labor market activity. That covers nearly every part of our lives.

Before this survey of baby boomers began in 1979, four other longitudinal surveys began in the 1960s of earlier generations. BLS began another survey in 1997 that represents people born in the years 1980 to 1984 and living in the United States at the start of the survey. We only still conduct the surveys of the two more recent generations, but we have learned so much from all the surveys. These surveys are some of the most analyzed in the social sciences. Researchers in economics, sociology, psychology, education, and health sciences have used the surveys to examine a broad range of topics. Here are just a few examples of what researchers have learned from the surveys:

- Nobel Prize winner James Heckman and his colleagues found that noncognitive skills, such as motivation and perseverance, are as important to future labor market success as are skills such as reading and math.

- People who obtain a GED or other exam-certified high school equivalent have labor market outcomes that are similar to those of high school dropouts, rather than to people who earn a regular high school diploma.

- The labor market effects of a 4-year college degree are similar for those who start at a 4-year college and those who transfer from a 2-year college to a 4-year college.

- Obesity is not only a health concern, but a labor market concern. Workers pay a price for obesity with lower wages and employment, and this price is higher for women than men.

- Low birth weight is a better predictor than cognitive test scores of whether people either work or attend school at ages 24 to 27. Birth weight also is a better predictor of adult wages.

You can find information about thousands of other research studies in the National Longitudinal Surveys bibliography.

Although we learn a lot each time we update our monthly and quarterly data on employment, compensation, prices, and productivity, there is so much we could not learn without these longitudinal surveys.

This is all possible thanks to Janet Norwood—and to the people who have agreed to participate in the surveys for so long—so that we can understand people’s paths over time!

United States Department of Labor

United States Department of Labor