An official website of the United States government

United States Department of Labor

United States Department of Labor

Since 2001, the airline industry has been affected by a number of external shocks, including terrorist attacks, volatile fuel prices, periods of challenging economic times, and an uncertain regulatory environment. In large part because of these factors, the industry has endured years of economic losses—$50 billion between 2001 and 2011—resulting in many bankruptcies and mergers.1 These losses have led airlines to focus on revenue-management strategies. One important way airlines have generated additional revenue is by adding surcharges and/or increasing ancillary fees for optional services or a la carte pricing. As an example, rather than airlines passing on higher fuel costs in the form of fare increases, fuel surcharges may be less noticeable. Passengers may be more likely to accept increases in fares if they know that fuel prices and fuel surcharges are rising in tandem. In addition, airlines have optimized capacity by eliminating and/or reducing the number of flights between some origins and destinations. These strategies have reduced the supply of available airline seats, giving airlines additional pricing power.

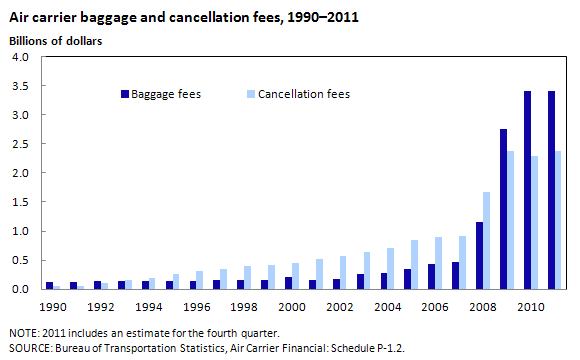

Although some airline fees have existed for many years, airlines recently have expanded the number of services for which they charge fees. In many cases, these new fees are for services that traditionally had been part of the service that passengers expected when buying an airline ticket. Examples include: fees for first and second checked bags, cancelling a ticket, seat selection, blankets and pillows, carry-on bags, making reservations over the phone or in person, and in-flight food and beverages. Revenue attributable to most of these fees is a small part of overall revenue, with the exception of baggage and cancellation fees. Baggage and cancellation fees are the most common and largest in terms of revenue, growing from $1.4 billion in 2007 to $5.7 billion in 2010.2 As these fees have risen, they have become an increasingly important contributor to airlines’ bottom lines. Chart 1 shows the growth in baggage and cancellation fees over the last two decades.

The exponential growth in baggage fees is due mainly to the implementation of new fees for passengers’ first and second checked bags—fees most airlines implemented in 2008 and early 2009. Prior to this, baggage fees were charged only for passengers with more than two checked bags, oversize bags, and overweight bags.

The changing regulatory arena surrounding air travel is affecting both passengers and airlines. In 2012, the U.S. Department of Transportation began requiring more transparency, when it comes to airline fees. This affects how airlines advertise and post fares, and how they disclose baggage fees on their websites. The government’s goal is to give travelers all available information, so they can plan their air travel accordingly.

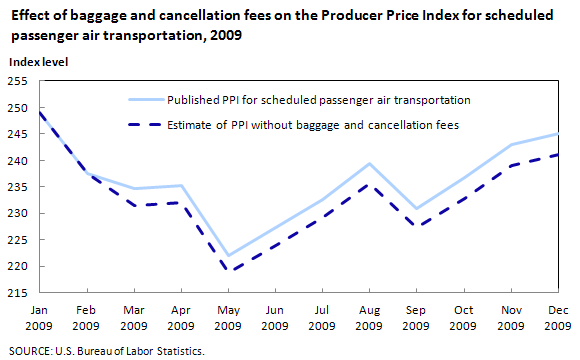

Since December 1989, the Producer Price Index (PPI) for Scheduled Passenger Air Transportation, which measures the average change in selling prices received by domestic airlines, has published monthly. In 2009, this index was adjusted to account for the imposition of new first and second checked-bag fees and for cancellation fees. Since then, this index has reflected the increasing importance of these fees. If the adjustment for new baggage and cancellation fees had not been made, it is estimated that the PPI for Scheduled Passenger Air Transportation would have been 1.6 percent lower in December 2009 than the final data indicated.3 This is illustrated in chart 2, which shows the published PPI for scheduled passenger air transportation and an estimate of what the index would have been without the adjustments for baggage and cancellation fees.

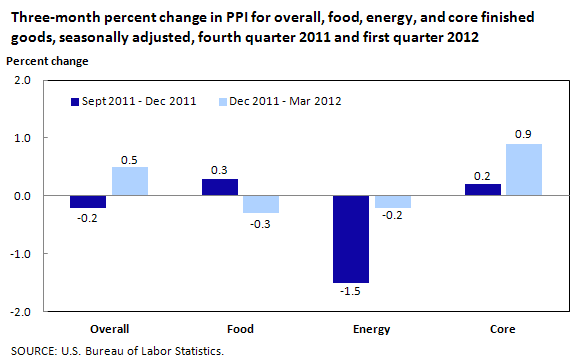

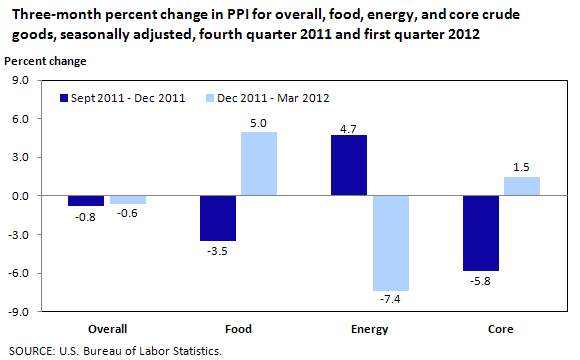

The Producer Price Index (PPI) for finished goods advanced 0.5 percent in the first quarter of 2012, compared with a 0.2-percent decline in the fourth quarter of 2011.4 The majority of this upturn can be traced to prices for finished goods less foods and energy, which increased 0.9 percent for the 3 months ended March 2012, following a 0.2-percent rise in the preceding quarter. Also contributing to the upturn in finished goods prices, the finished energy goods index edged down 0.2 percent in the first quarter, after falling 1.5 percent for the 3 months ended December 2011. In contrast, prices for finished consumer foods moved down 0.3 percent in the first quarter, following a 0.3-percent rise in the fourth quarter. At the earlier stages of processing, prices received by manufacturers of intermediate goods increased 1.1 percent for the 3 months ended in March, after decreasing 1.0 percent in the prior quarter. Most of this reversal is attributable to a similar first-quarter upturn in the index for intermediate goods less foods and energy. Prices for intermediate foods and feeds and intermediate energy goods inched up, after declining in the previous quarter. From December to March, the crude goods index fell at about the same rate as in the final quarter of 2011, 0.6 percent, compared with 0.8 percent. In the first quarter, lower prices for crude energy materials outweighed higher prices for crude foodstuffs and feedstuffs and core crude goods.5

Across the stages of processing, the PPIs for goods other than foods and energy provide a varied picture of inflation for the last 6 months. The shift in prices for core crude goods was led by the indexes for nonferrous ores and scrap, which rose in the first quarter of 2012, following steep declines in the fourth quarter of 2011. Likewise, upturns in prices for grains and oilseeds also contributed to this reversal. Prices for many lightly processed materials included in the intermediate core index also moved up from December to March, after falling in the preceding quarter: industrial chemicals, plastic resins, synthetic rubber, nonferrous primary metals and mill shapes, and steel mill products. In contrast, the index for more highly processed components for manufacturing inched up at a 0.3-percent rate for the second consecutive quarter. Within finished goods, the modest acceleration in prices for goods other than foods and energy was led by an upturn in prices for light motor trucks, as well as the index for pharmaceutical preparations, which rose at a faster rate in the first quarter of 2012 than in the fourth quarter of 2011.6

On April 4, 2012, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that total U.S. light duty motor vehicle sales for March 2012 were 14.3 million units, on a seasonally adjusted annual basis. This figure was 9.9 percent above its year-ago level and 22.5 percent higher than 2 years earlier. Furthermore, February’s 15.0 million units reflected the best monthly sales figure in the United States in more than 4 years.7 In terms of recent U.S. gross domestic product, after stalling at the start of 2011, the rate of growth in U.S. gross domestic product slowly gained momentum through the remainder of 2011.8

The PPI for finished goods moved up 0.5 percent for the 3 months ended March 2012, subsequent to a 0.2-percent decline in the fourth quarter of 2011. Accounting for more than half of this upturn, prices for finished goods less foods and energy rose more from December to March than in the prior 3-month period. The decrease in the index for finished energy goods slowed in the 3 months ended in March compared with the previous quarter. By contrast, prices for finished consumer foods turned down in the first quarter of 2012 after rising from September to December. (See chart 3.)

The index for finished goods less foods and energy advanced 0.9 percent for the 3-month period ended in March compared with a 0.2-percent gain from September to December. Prices for light motor trucks rose 1.2 percent from December to March, after declining 1.0 percent for the 3 months ended in December. The index for plastic products also turned up in the first quarter of 2012. Prices for pharmaceutical preparations increased more in the 3 months ended in March than in the preceding 3 months. Conversely, the increase in the passenger cars index slowed to 0.1 percent for the 3-month period ended in March, following a 0.7-percent advance in the fourth quarter of 2011. Cigarette prices also moved up at a slower rate from December to March, compared with the prior 3-month period. The index for nonwood commercial furniture declined in the first quarter of 2012, after rising from September to December.

Finished energy goods prices moved down 0.2 percent in the first quarter of 2012, compared with a 1.5-percent decline for the 3 months ended in December. From December to March, lower prices for residential natural gas, residential electric power, and liquefied petroleum gas more than offset higher prices for gasoline, diesel fuel, and home heating oil.

For the 3 months ended in March, prices for finished consumer foods fell 0.3 percent, subsequent to a 0.3-percent increase for the preceding quarter. Leading this downturn, beef and veal prices fell 2.7 percent in the first quarter of 2012, after rising 3.6 percent for the 3 months ended in December. The index for eggs for fresh use also turned down in the 3-month period ended in March. Prices for natural, processed, and imitation cheese decreased at a faster rate, compared with the fourth quarter of 2011. In contrast, the decline in the index for fluid milk products slowed to 3.9 percent from December to March from 7.3 percent in the prior 3-month period. Prices for russet potatoes turned up in the first quarter, following a decrease in the final 3 months of 2011, and the index for soft drinks rose in the 3 months ending in March, after registering no change from September to December.

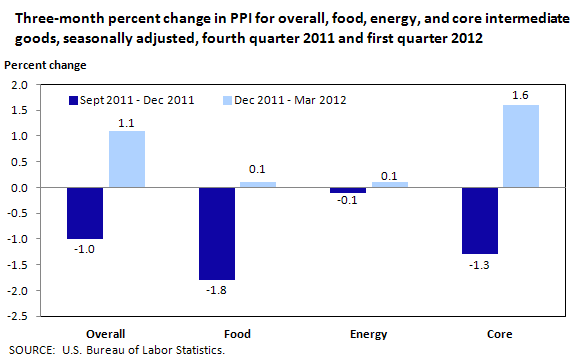

The PPI for intermediate materials, supplies, and components rose 1.1 percent in the 3-month period ending March 2012, subsequent to a 1.0-percent decrease in the 3 months ended in December 2011. This upturn was broad based, with prices for intermediate materials less foods and energy, intermediate foods and feeds, and intermediate energy goods all rising from December to March, after decreasing in the fourth quarter of 2011. (See chart 4.)

Prices for intermediate goods less foods and energy increased 1.6 percent in the first quarter of 2012, following a 1.3-percent drop in the prior 3-month period. The index for primary basic organic chemicals led this upturn, surging 14.0 percent from December to March, subsequent to falling 15.7 percent in the fourth quarter of 2011. Prices for nonferrous metals, plastic resins and materials, steel mill products, and synthetic rubber also advanced in the 3 months ended in March, after declining from September to December. Conversely, the fertilizer materials index moved down 7.3 percent from December to March, following a 4.1-percent increase in the previous 3-month period.

The index for intermediate foods and feeds inched up 0.1 percent for the 3 months ended in March, subsequent to a 1.8-percent decrease in the fourth quarter of 2011. Prices for prepared animal feeds led this upturn with a 2.5-percent advance from December to March, following a 6.1-percent decline in the previous quarter. The index for wheat flour also turned up, after declining in the 3-month period ended in December. Prices for fluid milk products decreased less in the first quarter of 2012 than they had in the final 3 months of 2011. Increases in the indexes for young chickens and soft drinks accelerated in the first quarter of 2012. Conversely, prices for natural, processed, and imitation cheese moved down at a faster rate in the 3 months ended in March, falling 8.7 percent, compared with a 2.2-percent decrease in the prior 3-month period. The index for shortening and cooking oil also fell more in the first quarter than in the prior 3 months. Prices for beef and veal turned down from December to March, after rising in the fourth quarter of 2011.

The index for intermediate energy goods edged up 0.1 percent from December to March, subsequent to moving down 0.1 percent in the previous quarter. For the 3 months ending in March, higher prices for gasoline, lubricating oil base stocks, and jet fuel outweighed lower prices for electric power, utility natural gas, and liquefied petroleum gas.

The PPI for crude materials for further processing fell 0.6 percent in the 3 months ended March 2012, following a 0.8-percent decline from September to December 2011. In the first quarter, lower prices for crude energy materials outweighed higher prices for crude nonfood materials less energy and for crude foodstuffs and feedstuffs. (See chart 5.)

The index for crude energy materials turned down 7.4 percent from December 2011 to March 2012, subsequent to a 4.7-percent advance for the 3 months ended in December. Crude petroleum prices declined 1.1 percent, following a 17.0-percent jump from September to December. The coal index also turned down, declining 5.5 percent, after advancing 1.7 percent in the fourth quarter of 2011. Prices for natural gas dropped 26.6 percent in the first quarter of 2012, compared with a 14.7-percent decline in the prior 3-month period.

The index for crude nonfood materials less energy turned up 1.5 percent in the first quarter of 2012, after declining 5.8 percent in the previous 3-month period. The index for nonferrous metal ores rose 4.1 percent following a 7.7-percent decrease in the fourth quarter of 2011. From December to March, prices for nonferrous scrap, corn, soybeans, and for hides and skins moved up, after falling in the prior 3-month period. Prices for high grade wastepaper declined less than in the September-to-December period. By contrast, the index for stainless and alloy steel scrap turned down 8.9 percent in the first quarter of 2012, after rising 7.0 percent in the preceding 3 months.

The index for crude foodstuffs and feedstuffs rose 5.0 percent from December to March, subsequent to a 3.5-percent decline for the 3 months ended in December. Prices for corn turned up 6.6 percent, following an 18.9-percent drop in the fourth quarter of 2011. The indexes for soybeans, wheat, and russet potatoes also rose in the first quarter of 2012, after declining in the prior quarter. Prices for slaughter steers and heifers advanced more in the first quarter, while the index for raw milk declined less than in the September-to-December period. By contrast, prices for slaughter barrows and gilts turned down 6.6 percent, following a 4.6-percent gain in the fourth quarter of 2011.

The PPI for the net output of total trade industries increased 1.1 percent in the first quarter of 2012, following a 0.8-percent decline in the fourth quarter of 2011. (Trade indexes measure changes in margins received by wholesalers and retailers.) Leading this upturn, margins received by wholesale trade industries climbed 2.4 percent for the 3 months ended in March, after falling 2.0 percent in the prior quarter. The margin indexes for clothing and clothing accessories stores, grocery stores, and non-discount department stores also moved up, following decreases in the fourth quarter. By contrast, margins received by discount department stores dropped 16.5 percent from December to March, after rising 18.2 percent in the preceding quarter. The margin index for automotive parts and accessories stores also turned down, following an advance in the fourth quarter.

The PPI for transportation and warehousing industries increased 2.6 percent for the 3 months ended in March, after moving up 0.6 percent in the fourth quarter of 2011. Over 30 percent of this faster rate of advance can be traced to prices received by the industry for couriers and express delivery services, which rose 5.8 percent, following a 0.5-percent decline in the prior quarter. The indexes for scheduled passenger air transportation and truck transportation rose more than they had in the fourth quarter. The United States Postal Service increased prices 2.3 percent from December to March, after no change in the preceding quarter. Prices received by line-haul railroads and deep sea freight transporters turned up in the first quarter. In contrast, the index for the scheduled freight air transportation industry fell 2.1 percent, after inching up 0.1 percent in the fourth quarter.

The PPI for the net output of total traditional service industries advanced 0.6 percent for the 3 months ended in March, after edging down 0.2 percent in the final quarter of 2011. About 40 percent of this upturn is attributable to the index for securities, commodity contracts, and other financial investments and related activities, which climbed 3.9 percent in the first quarter, following a 1.1-percent decrease in the preceding quarter. Prices received by the industries for passenger car rental and for non-casino hotels and motels also increased, after falling in the fourth quarter. The indexes for insurance carriers and related activities and for offices of lawyers rose more in the first quarter than in the previous quarter. In contrast, prices received by hospitals inched up 0.3 percent from December to March, following a 0.7-percent advance in the prior quarter.

This BEYOND THE NUMBERS report was prepared by staff in the Division of Producer Prices and Price Indexes, Office of Prices and Living Conditions, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Email: ppi-info@bls.gov; telephone: (202) 691-7705.

Information in this summary will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 691-5200. Federal Relay Service: 1 (800) 877-8339. This summary is in the public domain and may be reproduced without permission.

1 Airlines for America (A4A), “U.S. Airlines Post Lower Earnings in 2011 Due to Rising Costs,” February 28, 2012, www.airlines.org/Pages/news_2-28-2012.aspx.

2 Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Air Carrier Financial: Schedule P-1.2, www.transtats.bts.gov/Tables.asp?DB_ID=135&DB_Name=Air.

3 This calculation is an estimate of the PPI for scheduled passenger air transportation without baggage and cancellation fees and was done specifically for this paper. This calculation estimates the index level if the adjustments for baggage and cancellation fees were not applied.

4 Price movements for PPIs described in this summary include preliminary data for the months of December 2011 through March 2012. All PPI data are recalculated 4 months after original publication, to reflect late data received from survey respondents. In addition, seasonally adjusted PPIs are recalculated on an annual basis for 5 years, to reflect more recent seasonal patterns.

5 Within the PPI stage-of-processing structure, indexes for goods other than foods and energy commonly are referred to as core indexes.

6 More highly processed intermediate and finished goods commonly exhibit price movements that are somewhat different from price movements for less-processed goods, because basic material costs tend to be a smaller portion of total costs for producers of more highly processed goods than for manufacturers of less-processed goods. Contracts and escalation agreements also can delay or mitigate the pass-through effect of early-stage price volatility at successive stages of processing.

7 To retrieve these data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis website, visit www.bea.gov/national/index.htm, find the subheading labeled “Supplemental Estimates,” then select the link titled “Motor vehicles (Excel),” and go to table 6 of this file. As of April 13, 2012, the following link takes the user directly to these data: www.bea.gov/national/xls/gap_hist.xls.

8Gross Domestic Product: Fourth Quarter and Annual 2011 (Third Estimate) Corporate Profits: Fourth Quarter and Annual 2011, BEA 12-11, Bureau of Economic Analysis, March 29, 2012, at www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2012/pdf/gdp4q11_3rd.pdf, table 1.

Producer Price Index staff, “How new fees are affecting the Producer Price Index for air travel ,” Beyond the Numbers: Prices & Spending, vol. 1 / no. 2 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2012), https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-1/how-new-fees-are-affecting-the-producer-price-index-for-air-travel.htm

Publish Date: Wednesday, May 02, 2012