An official website of the United States government

United States Department of Labor

United States Department of Labor

Using predicted shaking intensity data from the U.S. Geological Survey and establishment location data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), this article matches establishment locations with shaking intensities and attempts to quantify the businesses, employees, and wages that would be affected by a 7.2 magnitude earthquake. This article updates several previous Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) articles, which provided economic damage estimates for businesses and employees in the San Francisco Bay area based on scenarios with lower magnitudes.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), there is a 72-percent chance of a magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake hitting the San Francisco Bay area and adjacent regions from 2014 to 2043. There is also a 98-percent chance of a magnitude 6.0 or greater earthquake during the same period.1 The Hayward Fault, which runs through the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay region, is the most likely source of a large earthquake striking Northern California, with a 33-percent probability of an earthquake occurring over a 30-year period. In contrast, the San Andreas Fault, which runs through the San Francisco Peninsula, has a 22-percent probability over the same period. A major earthquake in Northern California, and the San Francisco Bay area, specifically, could damage residences, businesses, public transportation, and utility systems, putting lives at risk. In addition, business losses could mount in proportion to the size of the earthquake event through direct property damage and business interruption. Aside from physical losses and disruption, business losses may also manifest in a long-term loss of customers, weakened ability of businesses to meet customer needs, and financial stress on the community or region.

This article attempts to identify the scope of labor market risks from a magnitude 7.2 earthquake in the San Francisco Bay area originating from either the San Andreas or Hayward Fault. In general, major earthquakes of magnitudes 7.0 or greater can devastate public infrastructure, rendering transportation and public utilities (such as gas, electricity, and water) out of service for days, weeks, or longer.

This article updates several previous BLS articles, which provided economic damage estimates for businesses and employees in the San Francisco Bay area.2 Past articles focused on the areas anticipated to face the most damage from an earthquake: those areas with very strong to severe shaking on the Modified Mercalli Index (MMI VII or greater).3 Similar papers have also been published by the USGS, the California Geological Survey, and private-insurance risk estimators. Some estimates were based on the loss of physical capital, although more recent studies have tried to account for the “business interruption” losses to firms. Economic-activity losses vary depending on the size of the earthquake scenario and the type of losses estimated (physical capital or business interruption). Accordingly, losses from a magnitude 6.9 Hayward earthquake vary widely, ranging from $23 billion for building-related losses to $210‒$235 billion in insured and uninsured economic damages.4

To match establishment locations with shaking intensities, this article identifies the businesses in probable “shaking zones” and uses Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) data to quantify the businesses, employees, and wages that could be at risk by shake zone intensity. Each data point in the QCEW dataset is geocoded with a latitude data point and a longitude data point, making it possible to map each establishment report against estimates of the expected range and area of damage zones, given an earthquake scenario provided by the USGS legacy shake catalog.5 However, because not all businesses in damaged areas will experience physical loss or business interruption, should an actual 7.2 magnitude earthquake occur, these estimates may not precisely match the actual losses incurred. That is, the actual effects on individual businesses are too specific to be captured based on relative damage areas. For example, while a business may provide its total number of employees in its establishment report, some employees may work remotely, which would limit the amount of actual business disruption from an earthquake.

The Hayward Fault runs directly through the heavily populated Alameda, Contra Costa, and Santa Clara counties. These three counties, and nearby San Francisco County, are the four most exposed counties in the region, in terms of potential damage, from earthquakes occurring on the Hayward Fault. The fault underlies a populous urban area, principally in Alameda County, and extends 74 miles along the eastern San Francisco Bay. Five other counties—Marin, Napa, San Mateo, Solano, and Sonoma—are further from the Hayward Fault but would still suffer some damage from an earthquake originating from the Hayward Fault. Combined, the 9 counties cover a 7,200 square-mile area and contain 6 million inhabitants, 320,000 business establishments, and 3.6 million jobs. As reported in a previous article, the Hayward Fault is known to generate a damaging earthquake every 150 years. The last event, which occurred in 1868, is now known as the “Hayward Earthquake.”6

The magnitude 7.2 earthquake scenario used in this analysis is a more powerful hypothetical natural disaster scenario than the magnitude 6.9 event analyzed in the 2007 BLS article and the magnitude 6.8 event explored in the 2016 BLS article. While a nominal increase of 0.3 or 0.4 magnitude may not seem large, such a slight increase represents roughly double the geographic area of a magnitude 6.9 earthquake, with 2.8 times the strength. Thus, care should be taken when comparing nominal values from this analysis to previous articles, especially if one does not consider natural population growth, consequent employment growth, and inflation. In addition, the wide difference in strengths from slight changes in magnitude should warn readers that earthquakes at a magnitude of 7.2 do not cause uniform damage across the affected areas. In other words, the actual losses of a Hayward Fault earthquake may be less, or greater, than the estimates in this scenario. Still, while the Hayward Fault presents the clearest threat, it is not the only potential source of an earthquake.

In addition to the Hayward Fault, multiple fault lines, including the San Andreas Fault, the Calaveras Fault, and the San Gregorio Fault, run through or are adjacent to the bay area. An earthquake originating from any of these fault lines could also cause significant economic losses. Figure 1 showcases the geographical location and the respective probabilities that each of these fault lines could be an earthquake originator.

Figure 1. Probabilities of selected fault lines causing an earthquake in the bay area

| Fault | Probability (percent) |

|---|---|

Hayward Fault | 33 |

Calaveras Fault | 26 |

San Andreas Fault | 22 |

Concord Fault | 16 |

Maacama Fault | 8 |

San Gregorio Fault | 6 |

Source: U.S. Geological Survey. | |

Note: See the USGS’ “Map of known active geologic faults in the San Francisco Bay region” webpage for the original figure.

Source: U.S. Geological Survey.

Of the multiple fault lines shown above, the most noteworthy is the San Andreas Fault line. While the San Andreas Fault line only has the third-highest probability of being the source of an earthquake, it runs through the San Francisco Peninsula rather than through the East Bay.

Would an earthquake along the San Andreas Fault line have more severe consequences than one originating from the Hayward Fault line? This article analyzes and compares potential economic damage for earthquakes originating from the Hayward and San Andreas Fault lines.

Two datasets were merged to prepare the analysis: a geographic file with shaking intensities from the USGS and an establishment-level microdata set containing employment and wages from QCEW’s Longitudinal Database (LDB). The geographic file of intensities, which uses MMI-scale measurements, gauges the effects of an earthquake at various distances from the fault rupture. The MMI scale ranges from I (not felt) to XII (total damage). (See figure 2 for an abbreviated version of the scale.) The analysis in this article focuses on those areas with estimated shaking intensities of VII or higher on the MMI scale. In particular, VII and VIII feature prominently in this analysis. As seen in figure 2, intensity levels VII and VIII refer to geographic areas that would likely experience very strong shaking and moderate damage and geographic areas that would likely experience severe shaking and moderate-to-heavy damage, respectively.

| Intensity | Shaking | Description/Damage | |

|---|---|---|---|

I | Not felt | Not felt except by a very few under especially favorable conditions. | |

II | Weak | Felt only by a few persons at rest, especially on upper floors of buildings. | |

III | Weak | Felt quite noticeably by persons indoors, especially on upper floors of buildings. Many people do not recognize it as an earthquake. Standing motor cars may rock slightly. Vibrations similar to the passing of a truck. Duration estimated. | |

IV | Light | Felt indoors by many, outdoors by few during day. At night, some awakened. Dishes, windows, doors disturbed; walls make cracking sound. Sensation like heavy truck striking building. Standing motor cars rocked noticeably. | |

V | Moderate | Felt by everyone; many awakened. Some dishes, windows broken. Unstable objects overturned. Pendulum clocks may stop. | |

VI | Strong | Felt by all, many frightened. Some heavy furniture moved; a few instances of fallen plaster. Damage slight. | |

VII | Very strong | Damage negligible in buildings of good design and construction; slight to modern in well-built ordinary structures; considerable damage in poorly built or badly designed structures; some chimneys broken. | |

VIII | Severe | Damage slight in specially designed structures; considerable damage in ordinary substantial buildings with partial collapse. Damage great in poorly built structures. Fall of chimneys, factory stacks, columns, monuments, walls. Heavy furniture overturned. | |

IX | Violent | Damage considerable in specially designed structures; well-designed frame structures thrown out of plumb. Damage great in substantial buildings, with partial collapse. Buildings shifted off foundations. | |

X | Extreme | Some well-built wooden structures destroyed; most masonry and frame structures destroyed with foundations. Rails bent. | |

Note: See the USGS’ “Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale” webpage for the original figure. Source: U.S. Geological Survey. | |||

The QCEW microdata contain geocoded establishment data, including the total employment counts and employee wages reported by individual businesses as of the first quarter of 2022. To construct the analysis, the employment and wage data from QCEW were overlaid on a geographic map with the USGS shaking intensity file. When spatially integrated (i.e., when the data points are overlaid) with the shaking intensity zones provided by the shaking intensity file, one can tabulate the potential business and labor market losses. Specifically, one can see the impacts of a major earthquake on wages and employment.

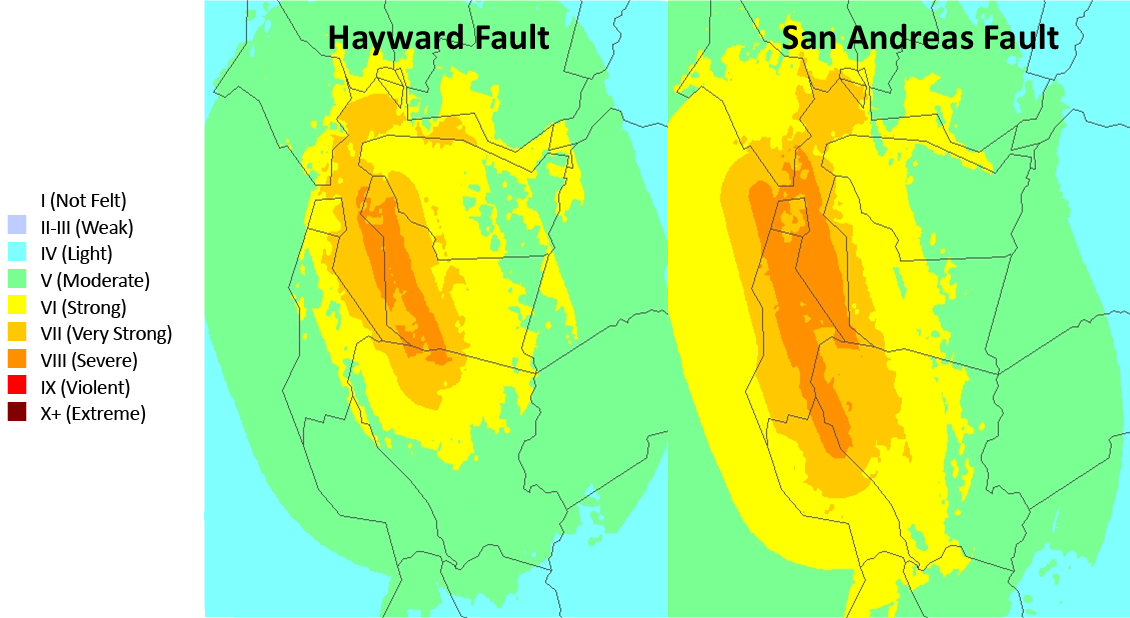

Based on USGS data, figure 3 depicts the dispersion of shaking intensity of business establishments into geographic zones. Dark orange and red areas designate those business locations with severe shaking and moderate-to-heavy damage (MMI VIII or greater). Business locations colored by light orange represent MMI VII intensity (very strong shaking areas with moderate damage).

Figure 3. Shaking zones: Hayward and San Andreas 7.2 magnitude earthquakes

Source: U.S. Geological Survey.

Total exposures for the nine counties in the San Francisco Bay area that are in the very strong shaking zone (MMI VII) and destructive shaking zone (MMI VIII or higher) include 118,165 establishments, 1.75 million jobs, and quarterly wages of $71.95 billion. For reference, the previous article in 2016 used 6 counties (dropping Napa, Sonoma, and Solano counties) and found that a magnitude 6.8 earthquake would impact 101,300 establishments, 1.54 million jobs, and quarterly wages of $37.5 billion. As a result of using a more powerful earthquake scenario and including more counties in the analysis, the number of establishments, jobs, and wages at risk are greater by 17 percent, 14 percent, and 92 percent, respectively.7 In the wide area circumscribed by both zones, the business, employment, and earnings exposures would fall primarily on Alameda County.

Using first-quarter 2022 QCEW employment and wage data (of which employment is an average of the 3 monthly numbers compiled), Alameda County accounted for 20 percent of all employed in the 9 counties examined and 14 percent of all wages. First-quarter 2022 employment and wage data, by county, are summarized in table 1; projected economic impacts from the earthquake to businesses are summed in table 2.

| County | Employment | Wages (millions of dollars) |

|---|---|---|

Total | 3,903,700 | 132,900 |

Alameda | 781,900 | 18,600 |

Contra Costa | 364,000 | 7,700 |

Marin | 107,000 | 2,500 |

Napa | 74,300 | 1,200 |

San Francisco | 728,200 | 32,100 |

San Mateo | 412,200 | 17,700 |

Santa Clara | 1,096,100 | 47,500 |

Solano | 137,300 | 2,200 |

Sonoma | 202,700 | 3,400 |

Source: Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW). | ||

As seen in table 2, an earthquake originating from the San Andreas Fault line would result in a much higher percentage of establishments and workers experiencing extreme damage when compared with an earthquake originating from the Hayward Fault.

| Total shaking and damage | Hayward | San Andreas |

|---|---|---|

Establishments, percent | ||

Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Moderate to heavy damage (8+) | 10.8 | 13.3 |

Moderate damage (7+) | 36.9 | 57.2 |

Light damage (6+) | 84.6 | 84.6 |

Very light damage (5+) | 95.4 | 98.6 |

Wages (millions of dollars), percent | ||

Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Moderate to heavy damage (8+) | 5.2 | 17.0 |

Moderate damage (7+) | 54.1 | 75.5 |

Light damage (6+) | 91.7 | 91.0 |

Very light damage (5+) | 95.7 | 97.0 |

Employment, percent | ||

Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Moderate to heavy damage (8+) | 8.8 | 13.7 |

Moderate damage (7+) | 44.7 | 61.9 |

Light damage (6+) | 85.7 | 84.9 |

Very light damage (5+) | 94.2 | 96.9 |

Notes: Establishments are rounded to tens, wages and employment are rounded to hundreds, percents are rounded to the nearest decimal, total employment is an average of the three months employment was collected over, and total wages is the total wages over the quarter (three months). Source: U.S. Geological Survey, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW). | ||

In the case of a 7.2 magnitude earthquake originating from the Hayward Fault, 36.9 percent of establishments are predicted to experience at least moderate damage. By contrast, if a 7.2 magnitude earthquake were to originate from the San Andreas Fault instead, 57.2 percent of establishments are expected to have at least moderate damage (a 55-percent increase).

Moreover, if the earthquake were to originate from the Hayward Fault, those businesses that are expected to experience at least moderate damage would account for 54.1 percent of wages in the area and 44.7 of employment. If a 7.2 magnitude earthquake were to originate in the San Andreas Fault, those businesses expected to experience at least moderate damage would account for 75.5 percent of wages and 61 percent of employment. This means that establishments that are expected to experience at least moderate damage from a 7.2 magnitude earthquake originating from the San Andreas Fault, would account for 38.5 percent more jobs and 39.6 percent more of wages than establishments expected to receive at least moderate damage from a 7.2 magnitude Hayward earthquake.

Even though some employees may work for establishments that are in areas expected to experience at least moderate-to-heavy damage, some of these workers may not actually report to the locations experiencing the damage. As a result, many remote workers could be counted as working in establishments affected by moderate-to-heavy damage, causing the analysis to overstate the economic impacts of the earthquake. By extension, given that the San Andreas earthquake is expected to affect large businesses (more likely to have remote workers) more than an earthquake originating from the Hayward Fault, it is possible that the real difference in economic damage between the two quakes could be overestimated here.8

The method of coupling MMI values with geocoded establishment data can be helpful in identifying the businesses, wages, and jobs most vulnerable to a hypothetical 7.2 magnitude earthquake; however, as previously noted, this method may overstate, or understate, the business interruption or losses that could occur.

The MMI values describe damage levels ranging from predominately-light damage to widespread, heavy damage. Even in the most damaged area, not all businesses will sustain damage that will curtail their activities, and some businesses that lose capability may return to normal operations quickly. In the same vein, due to expanded telework arrangements since 2020, businesses may experience disruptions to operations differently across industries.9 For example, employees in the information sector are more likely to perform work from home more frequently and are typically less reliant on a central physical office. Therefore, such establishments may experience reduced impact on operations than, for instance, a manufacturing entity if remote workers’ homes are not in earthquake damage zones. Industries with higher rates of telework may be more prevalent in the areas affected by an earthquake in the bay area (for example, tech companies).

Focusing on direct damage to a region’s businesses, however, may understate the impact an earthquake can have on firms adjacent to the impacted area, in terms of both geography and supply chains. Some businesses cluster in regions to be near customers and suppliers. If the relationship was interrupted by an earthquake, both customers and suppliers could be severely affected. For example, if business A was dependent on business B for inputs or for delivering their products, business A would be heavily impacted if an earthquake negatively impacted business B. Because the area is a vital transportation hub, the expected loss of life and damage to infrastructure and utilities (natural gas, electricity, or water) could also interrupt the flow of goods and services in Northern California, and the United States as a whole.10

Finally, the data used in this analysis specifically predicts the number of establishments, wages, and jobs that could be affected by a 7.2 magnitude earthquake. As such, it does not capture the economic impact of the emotional toll that an earthquake can have. For example, emotional distress from losing a family member may prompt some workers in the area to take bereavement leave. Due to the broad and, in some respects, abstract nature of the potential economic impacts of the emotional toll of an earthquake, that aspect of the economic impact is beyond the scope of this article.

Magnitude 7.2 earthquakes originating from either the Hayward or San Andreas Faults, as mapped by USGS intensity models, would likely produce a devastating shock to the bay area’s economy. In the San Francisco Bay area, the number of workers has grown 8.9 percent since 2014. Similarly, the potential losses from a large earthquake on the Hayward Fault have increased for affected counties since our previous estimate in 2007. Nevertheless, because the San Andreas Fault runs directly through the San Francisco Peninsula, an earthquake originating from the San Andreas Fault has the potential to surpass the total economic damages and spread of economic damage wrought by a similar magnitude earthquake originating in the Hayward Fault.

A significant proportion of the workforce in the nine most affected counties would be directly exposed to the shaking effects of a magnitude 7.2 East Bay or Peninsular earthquake. The direct effects would likely vary by business and location and would also be accompanied by secondary effects (for example, disruptions to infrastructure, such as transportation and public utilities). First response efforts to a 7.2 magnitude earthquake may be hampered by the extent of the damage to the healthcare and social assistance sectors. In addition, this level of exposure to strong or severe shaking could adversely affect every stage of recovery. For example, longer-term recovery may also be delayed due to the impacts on manufacturing and retail.

The potential economic consequences to employers and workers in the San Francisco Bay area could be widespread and would likely have an effect on the state economy. In turn, because of the far-reaching economic ties between firms and industries in California and the national economy, the latter could also be hampered. By using MMI values with geocoded establishment data to identify establishments, jobs, and wages most vulnerable to such an earthquake, this article helps quantify the economic effects that could result from a 7.2 magnitude earthquake in the bay area.

DISCLAIMER: The purpose of this article is to describe the labor market risks in the event of two possible earthquake scenarios. BLS is not making a specific earthquake prediction. However, the U.S. Geological Survey Working Group on California Earthquake Probabilities published two reports analyzing the risk of an earthquake occurring along the Hayward Fault: "Earthquake probabilities in the San Francisco Bay region: 2002–2031" in 2003 and "Forecasting California’s earthquakes—What can we expect in the next 30 years?" in 2008. The working group was composed of scientists from the federal government, state governments, private industry, consulting firms, and academia. The projected Modified Mercalli Intensity scale values associated with the hypothetical Hayward earthquake are from the U.S. Geological Survey Shakemap archives.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: This article was prepared with help from Tian Luo, an economist with the Office of Field Operations, Division of Economic Analysis and Information, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Chris Rosenlund, Assistant Commissioner for Regional Operations for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

If you are deaf, hard of hearing, or have a speech disability, please dial 7-1-1 to access telecommunications relay services or the information voice phone at: (202) 691-5200. This article is in the public domain and may be reproduced without permission.

Nicholas Chung, "Labor market risks of a magnitude 7.2 earthquake in the San Francisco Bay area: an update and extension," Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, August 2025, https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2025.13

1 According to the USGS’ “When will it happen again?” webpage, an earthquake of 6.0 magnitude or higher remains a significant risk for the bay area, both in terms of probability and in terms of economic damage potential.

2 The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics previously published several research papers on the potential damage from a major earthquake in the bay area. See “Labor market risks of a 6.9 magnitude earthquake in Alameda County,” Regional Report (September 2007); “Labor market risks of a magnitude 7.8 earthquake in southern California,” Regional Report (June 2011); Richard J. Holden, Tian Luo, Anne Heidl, and Amar Mann, “Labor market risks of a magnitude 6.8 Hayward Fault earthquake in the San Francisco Bay area: an update,” Beyond the Numbers: Regional Economies 5, no. 15 (October 2016).

3 As noted in “Labor market risks of a magnitude 6.8 Hayward Fault earthquake in the San Francisco Bay area: an update,” Beyond the Numbers: Regional Economies 5, no. 15 (October 2016), seismic intensity is a measure of the effects of an earthquake at different sites. Intensity differs from magnitude in that the effects of any one earthquake vary greatly from place to place, so there may be many intensity values measured from one earthquake. Each earthquake, on the other hand, should just have one magnitude (often measured by the moment magnitude scale or the Richter scale). The Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) scale is commonly used to gauge the severity of earthquake effects. Intensity ratings are expressed as Roman numerals between I (the least destructive) and XII (the most destructive). At MMI-VII, while damage may be slight in specially designed structures, there is often considerable damage and partial collapse even in substantial ordinary buildings.

4 Rui Chen, David Branum, and Chris J. Wills, “HAZUS loss estimation for California scenario earthquakes,” California Geological Survey, June 2009. Also see, Risk Management Solutions’ press release, from October 31, 2008, concerning a study with losses from a magnitude 7.0 Hayward earthquake.

5 See the USGS legacy shake catalog.

6 This earthquake was known as “The Great San Francisco Earthquake” until 1906 when a larger earthquake, caused by a rupture in the San Andreas Fault, assumed that eponymous name.

7 Another possible cause for the increase in the number of establishments, jobs, and wages at risk is changes in business dynamics in the bay area over time.

8 See the latest Business Response Survey: “BRS 2022 Charts,” Business Response Survey, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, last modified March 22, 2023.

9 See the latest Business Response Survey for more data on remote work: “BRS 2022 Tables,” Business Response Survey, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, last modified March 22, 2023.

10 For example, see the official webpage of the Port of San Francisco, https://californiaports.org/ports/port-of-san-francisco/.