An official website of the United States government

United States Department of Labor

United States Department of Labor

The COVID-19 pandemic, which began in 2020, significantly changed the dynamics of working life. To help capture these changing dynamics, we examined publications that the International Labour Organization published during this period. This article aims to determine what kind of discussions are made within the framework of these publications in the context of COVID-19 by period and region. Thus, we researched the most intense discussion themes and tried to discover the global agendas of the labor markets. Within the scope of this article, we downloaded, classified, and examined a total of 1,062 publications (reports, webinars, and bulletins) published between January 2020 and April 2021. As a result of the analysis, we saw that the themes of working hours, informal workers, vulnerable workers, decent work, social protection, remote working, skills development, social dialogue, and labor standards were dominant.

Discussions of remote work and the digitalization of the workspace have gained momentum since the early 2000s. Following the onset of the pandemic in 2020, we have seen a shift in the production process toward remote work. With the prevalence of digital business platforms in many countries of the world, work has become more independent of space and distance.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) produces reports and documents for all subjects related to work. The ILO has produced a substantial number of publications in the context of COVID-19 and the transformation in working life it has caused. This article aims to find, using an exploratory analysis, themes that stand out in each period and region in ILO publications. Labor standards are not fixed, and the forms of work and its conditions will continue to evolve. This article also aims to evaluate the possible changes in working life after the pandemic period, such as changed expectations or potential policies. By analyzing the text of previous ILO publications, we seek to read the future from the past and shed light on previous research that has been overlooked despite describing the current dynamics of working life. The ILO has produced rich discussions and an enormous amount of literature about what the future of work might look like. Labor markets in developing and developed countries will likely undergo significant transformations in the following years and decades.1 What the future of work looks like, then, depends heavily on how those transformations play out. Popular scenarios include ones with technological revolution, ecological conversion, decent work, and the dismantling of labor laws.2 ILO is a crucial organization in global economic policymaking.3 The ILO reports can serve as indicators of future trends in the labor market and can follow the global market agenda ahead of time.4 For example, technological unemployment was at the center of policy debates about automation processes in the 1960s, and the ILO archives show that many of today’s policy recommendations were first put forward in the ILO at that time.5 Also, ILO first introduced the concept of decent work at the 87th session of the International Labour Conference in 1999.6 After that, decent work became, and continues to be, one of the central concepts of working life.7 For this reason, we believe that the results we obtain from the ILO documents we have analyzed can help forecast the future of the labor market.

For this article, we downloaded 1,062 publications (reports, webinars, and bulletins) from the ILO. We divided the publication into 5 quarters, from January 2020 to April 2021. First, we created word frequencies and clouds with the NVivo software, then we created thematic topics by evaluating words together with their word-tree components. We looked for themes in the publications with an eye toward how we would separate them via our coding, and we cross-checked the results of the automated classification to confirm that the classifications were accurate. With the data classified, we then analyzed by period and by region.

This article consists of four parts. The first part is devoted to theoretical explanations of the thematic components that emerged within our qualitative research. In the second part, we explain our method. The third part is about our findings. In that part, we see which of the most frequently used words, sentences, and themes are associated, and we reveal the level of discussions within the topics presented. That part also compares the intensities of discussion on the themes over the ILO regions and selected 5 quarters. The last part is devoted to our discussion and conclusion. In that section, we combine and evaluate all thematic components.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ILO has closely followed the effects of the pandemic on working life and the business world. The global economic crisis that emerged because of the pandemic has increased the importance of public interventions and regulations for workers and employers. To shield their vulnerable populations from the direst effects of the crisis, governments have responded with an unprecedented expansion of economic assistance and social protection. These expansions have included job retention measures, support to enterprises in severely impacted sectors, expansion of unemployment benefits, and social assistance aimed at the poorest and most vulnerable.8 All these practices have had a place in the publications of the ILO, in the form of actual practices as well as recommendations to member countries. In the COVID-19 and Enterprises briefing notes, the ILO states that the COVID-19 pandemic has been affecting enterprises of all sizes and types. In this context, the importance of business and jobs sustainability is emphasized in the fight against increasing global unemployment and working poverty. The briefing notes also emphasize supporting small and medium enterprises in their effort to develop contingency plans to protect their workers and businesses from the consequences of sudden disasters.9 Besides tax policy and tax administration measures, governments could also consider social security benefits, direct labor subsidies, wage subsidies, leave and self-isolation support, business cash flow, short-time work support, and unemployment payment.10 In addition, the ILO briefing notes also examined the effectiveness of government interventions such as direct grants, selective tax advantages (and advance payments), state guarantees for loans taken by companies from banks, subsidized public loans to companies, safeguards for banks that channel state aid to the real economy, and short-term export credit insurance.11

Remote work and digital labor platforms (like gig work), which became widespread during the COVID-19 pandemic, radically changed working conditions, working hours, and working arrangements and increased the importance of decent work. In times of crisis, International Labor Standards provide a strong foundation for critical policy responses that focus on the crucial role of decent work in achieving a sustained and equitable recovery. These standards, adopted by representatives of governments, workers and employers, provide a human-centered approach to recovery, including triggering policy levers that both stimulate demand and protect workers and enterprises.12 There are 10 indicators of decent work:

· Employment opportunities

· Adequate earnings and productive work

· Decent working time

· Combining work, family and personal life

· Work that should be abolished

· Stability and security of work

· Equal opportunity and treatment in employment

· Safe work environment

· Social security

· Social dialogue, workers’ and employers’ representation.13

During the COVID-19 pandemic, ILO gave special attention to vulnerable population groups, especially migrant workers, women workers, workers with disabilities, elderly workers, and informal workers.14 For millions of workers around the globe (especially manual laborers), working from home is not an option. This group of workers, at various points during the COVID-19 pandemic, was forced to stay home or was under (temporary) unemployment.15

The lockdown and confinement phase of the pandemic has provided an excellent opportunity to invest in retraining staff to develop new skills or become certified in the skills they already have. One of the impacts of COVID-19 has been the proliferation of free online courses. The ILO has taken advantage of digital technology and social media to encourage people to access online courses and on-the-job tutorials. The ILO already uses digital communication channels to raise awareness of occupational safety and health in the context of COVID-19 in some countries.16

We collected the 2020 data within the scope of the research from the official website of the ILO between March 22, 2021 and April 6, 2021.17 We carried out this search by typing the keyword “COVID-19” in the search bar on the site. At the time of writing, according to the search result, there were 2,373 results in 2020 that were displayed on 238 pages in total. There were 10 documents per page (with 3 documents displayed on the last page, number 238).

After the search result for the keyword “COVID-19,” we preserved the way the official site presented the data, and we then prepared an Excel file and began to record the data.18 We collected the data in the order the site presented them (nonchronologically) and wrote them on each line separately in our database. We then put them in chronological order for 2020. After we reordered the results, we labeled them with the relevant quarter. The quarters for 2020 are determined as follows: quarter one with January–February–March data, quarter 2 with April–May–June data, quarter 3 with July–August–September data, and quarter 4 with October–November–December data.

We collected the data for 2021 through the same process. A total of 815 documents for 2021 on the official site of the ILO were displayed on 82 pages. We started the data collection process for the 2021 data on April 14, 2021 and finished on April 16, 2021.

The total number of data recorded for 2020 and 2021 is 3,188. After we removed files that were not capable of being textually analysed (such as those in video or photo formats) as well as duplicate items, we had 1,062 files from the ILO site remaining. We performed no other filtering on the documents except to ensure that the word COVID-19 was present and the publication date was within the sample period.

In this article, we do not test a previous hypothesis, and instead let the features of the data guide us. Because of this nature, it is an inductive analysis.19 Since our aim is to examine the relationships between the data in detail from a holistic perspective and to make inferences, we decided that “qualitative research” was the most appropriate method.20 To reach high-level themes from low-level concepts, we decided to use the grounded theory methodology.21 The labor market experiences of the research team over the years, their readings, and academic studies have significant value in thematic classification. In addition, if the dataset is developed in the future, we have already made an infrastructure for future studies on the subject because of the convenient structure of embedded theory analysis.

We chose qualitative data analysis as the research method, and we preferred the content analysis method because it would be the first detailed analysis of the data. In order to reduce human error in the research method and to facilitate many processes, we decided to use NVivo, a computer-aided qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS).22 CAQDAS is not a program that allows all operations to be performed automatically by loading the data into the program, but it is rather a tool that automates the processes of a research design.23 The introduction of these codes is called manual coding, and this forms the basic infrastructure (code structure) of the rest of the research.

The manual coding section resulted in the creation of four main titles (with various subtitles) and defined the most fundamental topics in the data. For the thematic analysis of the publications, we manually coded with the help of NVivo. NVivo assigned the ILO-term data to the categories we created, and to ensure that all the data were properly assigned by NVivo, we manually checked each assignment to confirm it was accurate (and if not, we reassigned the term to the proper category).

In this article, we carry out our analyses at various levels with the help of manual and automatic coding. First, we perform a single-level analysis to determine document type. (See chart 1).

| Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Publication | 269 |

| Meeting document | 171 |

| Document | 146 |

| Report | 113 |

| Briefing note | 89 |

| Fact sheet | 52 |

| Presentation | 41 |

| Brochure | 34 |

| Statement | 21 |

| Periodical publication | 18 |

| Agenda | 17 |

| Instructional material | 12 |

| Book | 11 |

| News | 11 |

| Project documentation | 10 |

| Record of proceedings | 10 |

| Working paper | 9 |

| Vacancy note | 6 |

| Resource list | 5 |

| Article | 4 |

| Audio | 3 |

| Conference paper | 3 |

| Record of decisions | 2 |

| Comment | 1 |

| Event | 1 |

| Informe | 1 |

| Progress report | 1 |

| Seminar | 1 |

| Note: ILO = International Labour Organization. Source: Authors' calculations from International Labour Organization publications. | |

According to our classification of the 1,062 documents, there are 269 general publications, 171 meeting documents, 146 featured documents, 113 reports, 89 briefing notes, 52 fact sheets, 41 presentations, 34 brochures, 21 statements, 18 periodical publications, 17 agenda documents, 12 instructional materials, 11 news items, 11 books, 10 project documentations, and 10 records of proceedings. Twelve categories, with fewer than 10 counts each, contain the remaining 37 items.

We then perform a dual-level analysis to determine the period and region relationship of the documents. (See chart 2.)

| Region | Q1 2020 | Q2 2020 | Q3 2020 | Q4 2020 | Q1 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | 23 | 192 | 90 | 126 | 104 |

| Europe | 2 | 11 | 12 | 5 | 17 |

| Asia | 10 | 51 | 80 | 97 | 63 |

| Africa | 1 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 9 |

| Americas | 4 | 48 | 29 | 19 | 11 |

| Arab states | 1 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 12 |

| 1 Not applicable. Note: ILO = International Labour Organization; Q = quarter. Regions are as defined by the ILO. Source: Authors’ calculations from ILO publications. | |||||

The majority of the documents in the analyzed dataset are global and 192 of the 534 documents classified as global were published in the second quarter of 2020. Out of 301 documents associated with the Asia–Pacific region, 97 were published in the fourth quarter of 2020. Finally, 111 documents are related to the Americas, 47 are related to Europe and Central Asia, 37 to the Arab States, and 32 to the African region.24

In the second stage, we counted word frequencies for all categories. Our aim here was to find the most common words in every category and create a study guide. When we ordered the meaningful words according to their frequency of use, it started to explain the central theme discussed in the relevant period in 1,062 publications.

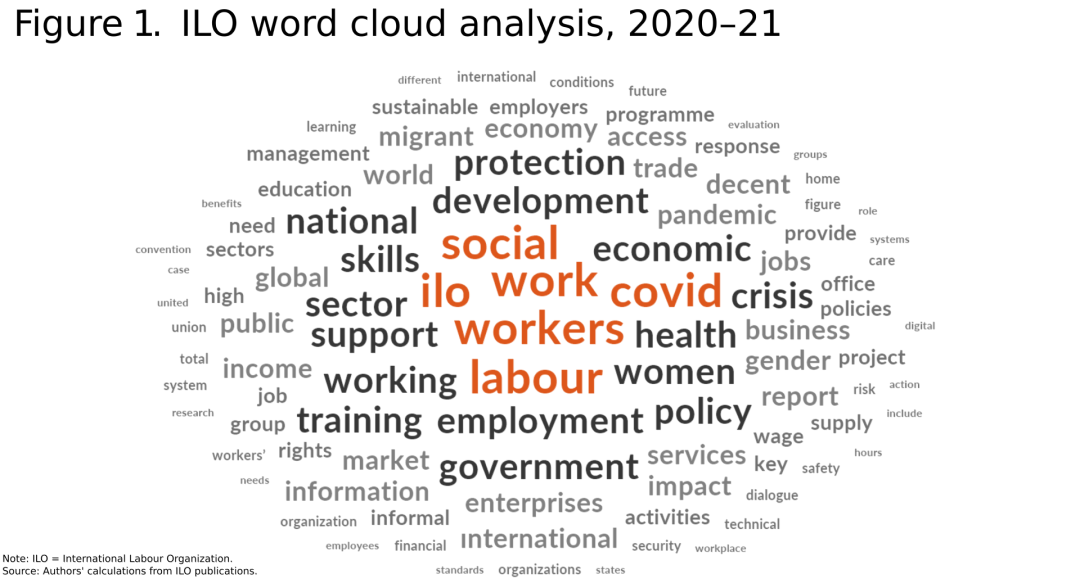

Word cloud analysis is the visual expression of the most mentioned words in a dataset. In word cloud analysis, the words that are mentioned the most are in the middle of the cloud and in large fonts while less frequently mentioned words are toward the edges of the cloud shape and in smaller fonts. Word clouds are used to visually reveal the words and values that may be overlooked in a frequency table, and they contribute to making the research results understandable for the reader.

NVivo software automatically analyzed all documents and determined the 1,000 most commonly used words in the documents.

In word cloud analysis, the most used words in the articles are “workers,” “work,” “labor,” “ILO,” “social,” “covid,” “employment,” “women,” “health,” “support government,” “sector,” “skills,” and “policy.” We took a subset of the top 1,000 words to be a subject for our more detailed analysis. The frequencies of the words that are used the most and of the words that we decided to remove from our analysis are given in table 1.

| Word | Count | Selected for word cloud |

|---|---|---|

| Workers | 39,925 | Yes |

| Work | 39,765 | No |

| Labor | 35,231 | Yes |

| ILO | 34,845 | Yes |

| Social | 30,712 | Yes |

| Employment | 25,447 | Yes |

| COVID | 25,148 | Yes |

| Per | 22,793 | No |

| Cent | 19,562 | No |

| Women | 18,794 | No |

| Countries | 16,216 | No |

| Development | 14,960 | No |

| Health | 14,732 | No |

| Support | 14,279 | No |

| Working | 13,449 | No |

| Government | 12,960 | Yes |

| Skills | 12,790 | No |

| Training | 12,596 | Yes |

| Economic | 12,511 | No |

| Sector | 12,502 | Yes |

| Policy | 12,448 | No |

| Protection | 12,197 | No |

| Measures | 12,078 | No |

| May | 12,058 | No |

| National | 11,996 | No |

| Including | 11,270 | No |

| Crisis | 11,120 | No |

| Pandemic | 10,545 | No |

| Services | 10,481 | No |

| Enterprises | 10,308 | Yes |

| Business | 10,225 | No |

| Market | 9,823 | No |

| Based | 9,754 | No |

| Gender | 9,673 | Yes |

| Data | 9,509 | No |

| Global | 9,267 | No |

| Time | 9,254 | No |

| World | 9,216 | No |

| New | 9,076 | No |

| Income | 9,028 | Yes |

| Jobs | 8,894 | Yes |

| Trade | 8,893 | Yes |

| Country | 8,720 | No |

| People | 8,478 | No |

| One | 8,354 | No |

| Public | 8,205 | No |

| Impact | 8,110 | No |

| Report | 8,086 | No |

| Economy | 8,075 | No |

| Information | 7,850 | No |

| Level | 7,807 | No |

| Decent | 7,770 | Yes |

| Interventions | 7,594 | Yes |

| Access | 7,534 | No |

| Migrant | 7,501 | No |

| Well | 7,425 | No |

| Wage | 7,411 | No |

| Job | 7,173 | No |

| Education | 6,924 | Yes |

| Rights | 6,814 | No |

| Provide | 6,759 | No |

| Sectors | 6,753 | No |

| Informal | 6,752 | No |

| Activities | 6,747 | No |

| Policies | 6,721 | No |

| Many | 6,671 | No |

| Employers | 6,665 | No |

| Office | 6,625 | No |

| High | 6,500 | No |

| Key | 6,422 | No |

| Response | 6,344 | No |

| Group | 6,339 | No |

| Number | 6,300 | No |

| Available | 6,298 | No |

| Youth | 6,258 | Yes |

| Use | 6,232 | No |

| Programme | 6,205 | No |

| Management | 6,092 | No |

| Poverty | 6,072 | Yes |

| Ensure | 6,038 | No |

| Financial | 6,013 | No |

| Figure | 5,977 | No |

| Security | 5,961 | No |

| Dialogue | 5,914 | No |

| Org | 5,901 | No |

| Union | 5,878 | No |

| Organizations | 5,857 | No |

| Related | 5,721 | No |

| Risk | 5,684 | No |

| Safety | 5,634 | No |

| Among | 5,617 | No |

| System | 5,590 | No |

| Total | 5,535 | No |

| Survey | 5,530 | No |

| See | 5,385 | No |

| OHS | 5,372 | Yes |

| Conditions | 5,331 | No |

| Entrepreneurship | 5,297 | Yes |

| Home | 5,252 | No |

| Digital | 5,246 | Yes |

| Note: ILO = International Labour Organization; OHS = occupational health and safety. Source: Authors’ calculations from International Labour Organization publications. | ||

On the basis of the most used words in the dataset, we decided to perform a word tree analysis of 22 words.25 We chose these 22 words because of our readings and field experiences. Word tree analysis is a qualitative data analysis tool that reveals the words used before and after a selected word or phrase and helps to obtain general information about the articles. After the word tree analysis (and discussions with experts), we classified the articles by topic and subtopic.

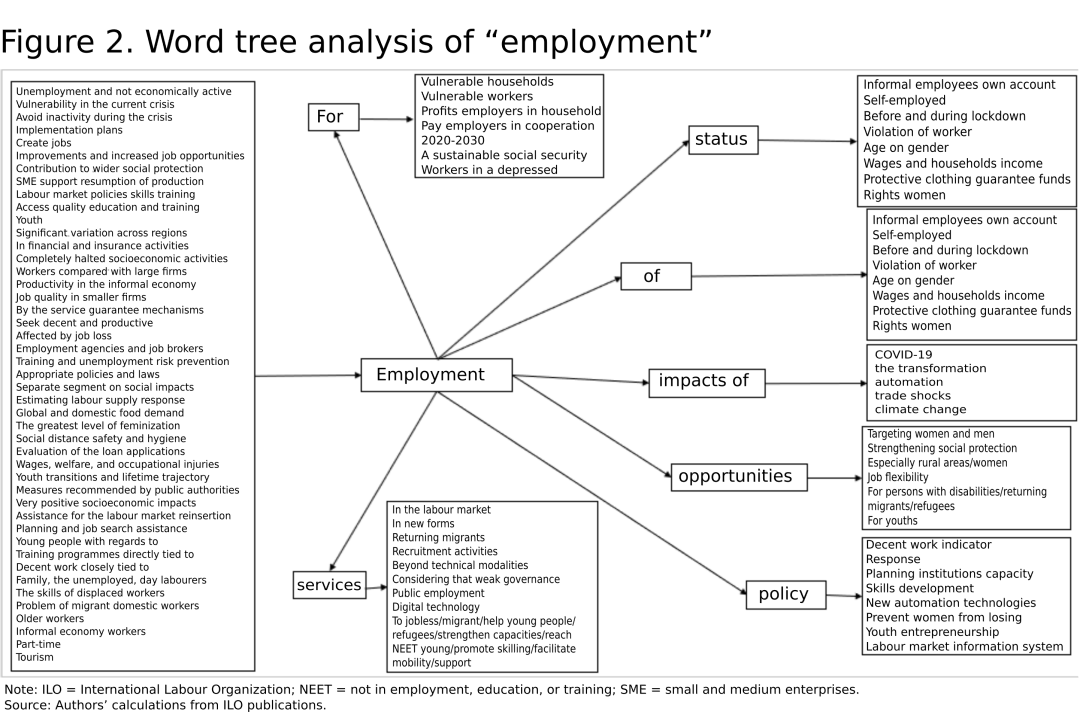

We prioritized the words obtained from the word tree analysis according to our experience and the objectives of the study. We then examined the three words before and after the selected words to look for patterns and associations.26 When all the documents were scanned, the word tree analyses began to provide us with more detailed information about general trends. To better understand word tree analysis, in figure 2, we give examples for the word “employment.”

During the word tree analyses, other concepts and commonly paired words in the documents emerged. For example, the use of the words “unemployment” and “arrangements” before the word “work” reveals that the concepts of unemployment and labor market regulations are mentioned together frequently in the documents.

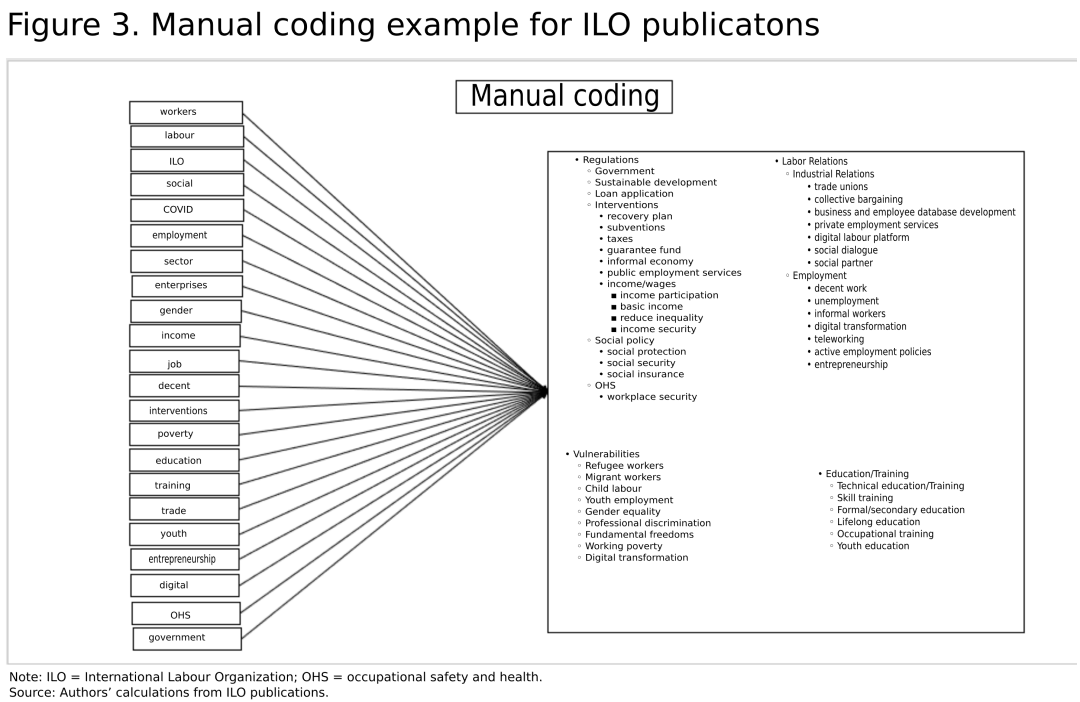

Some of the analyzed words, such as “employment,” have multiple-level expressions associated with them, while for other words the analysis is single level. We grouped themes under main headings. (See figure 3). With the manual coding, the points in the documents that we consider essential and the points that we want to emphasize are revealed. When the words identified during the manual coding phase are associated with close components from the covered ILO publications, all of the identified words can be grouped under four main headings: “regulations/interventions,” “labor relations,” “vulnerabilities,” and “education/training.”27

The four main headings, which we determined from the word trees we formed by manual coding, express the macro topics that the 1,062 publications focus on. After we completed the regional and periodical thematic discoveries, we classified the identified themes under these four main headings.

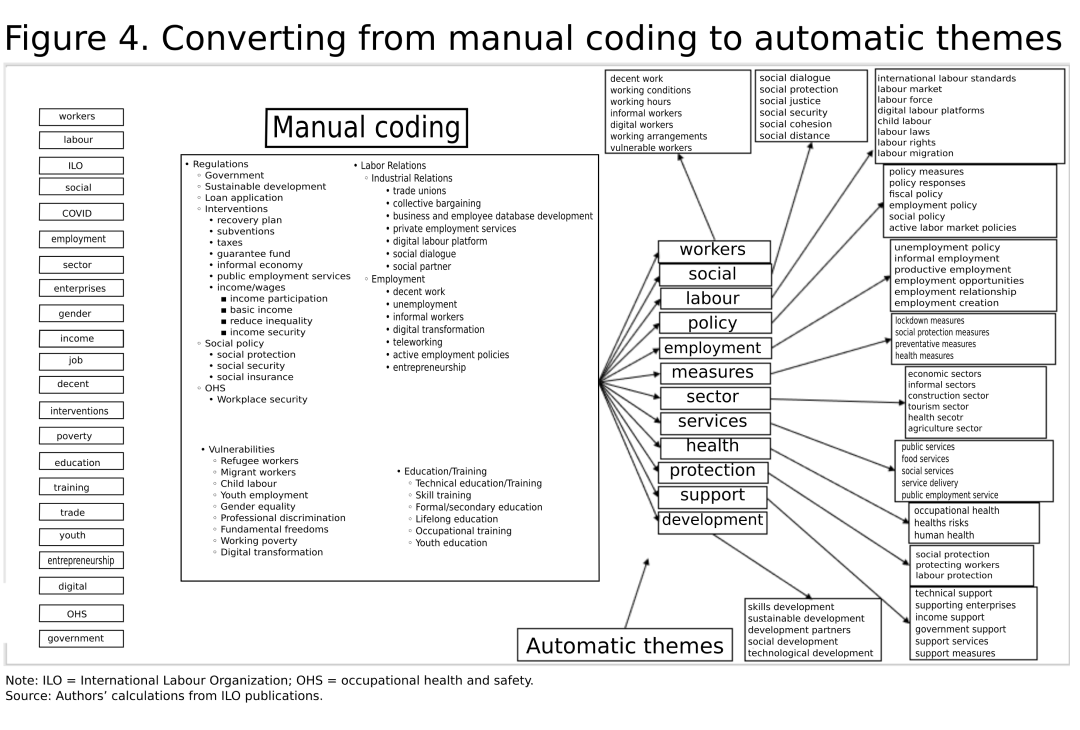

After the manual coding process, we determined the repeated focal points in ILO documents within the themes that emerged as a result of manual coding. The recurring focal points in the ILO documents were revealed by the word cloud and word tree analysis as well as our own experience, and we classified the topics that emerged. Thus, it was possible to separate the most popular issues under the main headings. Topics resulting from automatic coding associated with manual coding are given in figure 4.

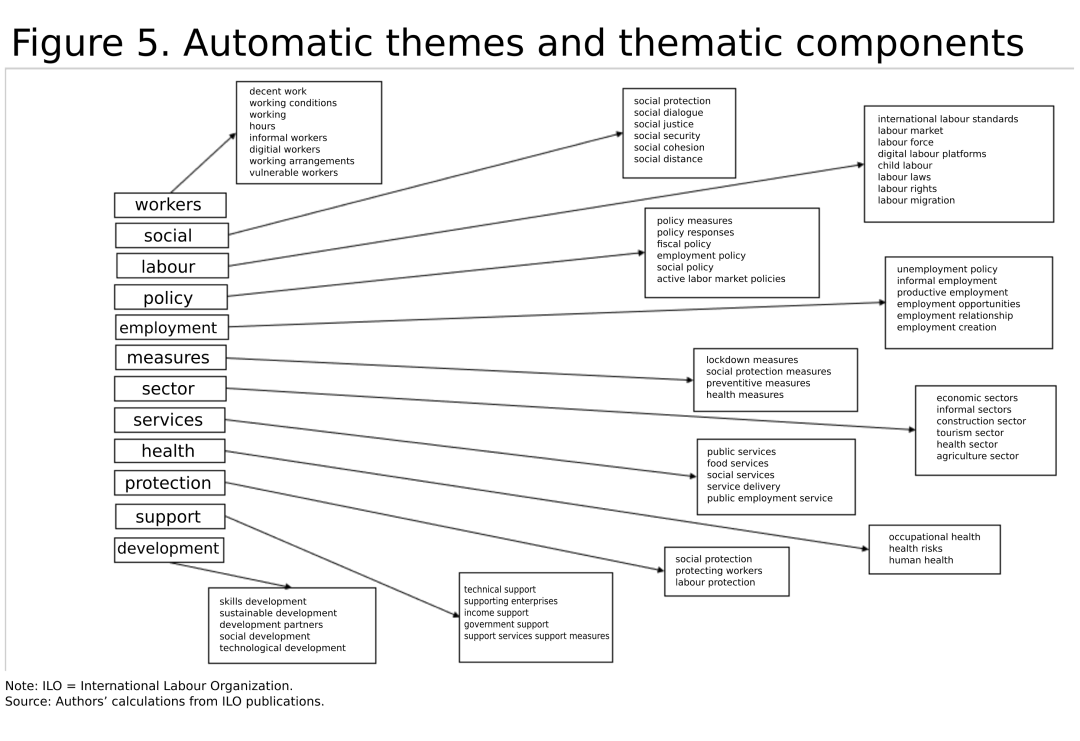

After we examined the themes from automatic coding, we narrowed our word list from 22 to 12. The remaining words are those that we found to be most closely related to the point of our study. With the automatic coding done after manual coding inferences, we could see which subjects were emphasized within the scope of the ILO during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Thus, we were able to conduct a detailed content analysis for each thematic component. The discovery process and content at the end of automatic coding are presented in figure 5.

The topics that stand out on a global scale within the scope of 12 main themes that emerged from the dataset we examined follow.

Social protection and support frequently appear in every theme.28 From the articles, we see that mentions of public aid became much more common and that social policies and new labor law regulations became more prevalent. In the articles that are under the employment and unemployment headings, we see warnings about the destruction of decent work. We find that decreasing employment opportunities, worsening working conditions, uncertain working hours, and increasing unregistered employment were all being discussed more and more. The reports state that the social dialogue mechanism, occupational health and safety, and general health conditions have all deteriorated. Some articles draw attention to the increase in digital labor platforms and comment that there was a weakening in social security rights and an increase in the number of vulnerable workers. A number of publications mention the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the construction, tourism, and agriculture sectors. The ILO publications also mention the difficulties encountered in public services, food services, and a deterioration in service delivery. Migrant labor and child labor issues also have a prominent place among the documents we examined.

From our results, it was possible to separate regional and periodical themes. When we analyzed by region, we were able to decompose the prominent issues according to each region.

According to the thematic intensities disaggregated in the ILO five-region classification, the most discussed issue in the Americas region was “working hours.” The ILO articles emphasized that unregistered employment had increased, labor rights had weakened, and labor laws had been inadequate in keeping up in a changing environment. The articles also noted that the region had quite a number of public policies for business development as well as for income support for its denizens. The articles from the region also emphasized the health system and the problems encountered in health services. There are also determinations regarding real minimum wage discussions and new union organizing movements.

The topic of “local workers” was frequently discussed in the articles from the Europe and Central Asia region. Because of a decrease in the working-age population, the issue of migrant labor and unregistered employment was at the forefront of the ILO articles. The publications emphasized that remote work was gaining momentum, working conditions were deteriorating, and vulnerable labor was increasing. Some reports focused on temporary government measures, the need to reduce informality, and the damage that the COVID-19 pandemic created in the services, tourism, and food sectors. The region’s articles also expressed the importance of support for workers and employers and gives recommendations for restructuring social security and insurance services. There were statements about the need to review the minimum wage policy, the increase in wage differences, and wage support. Some articles also suggested reviewing social assistance payments’ structure, introduced new human health-oriented approaches to social policies, and stressed the importance of institutional labor market practices and occupational health and safety.

“Migrant workers and vulnerable workers” were the most frequently reported issue in the Asia and Pacific region. Forced labor, child labor, and the inadequacy of labor laws were heavily discussed. The ILO articles emphasized labor force participation difficulties and the need for improvements to labor market information systems. Articles also discussed the forms of informal employment and flexible work as well as what policies governments should take toward immigrants. The destruction of the supply chain of food services and the disruptions in social services were also a focus. The articles for the region stated that the social protection system should be improved and that wages should be protected, and overall they emphasized the importance of supports for both employers and workers. There were also discussions on providing more technical and institutional support for talent and capacity building.

In the African region, the most intense debate within the ILO was the “informal economy.” Skill development and obtaining valid work permits were among the critical issues. The publications highlighted migrant labor, employment contracts, and the inadequacy of labor demand. Many reports stressed the necessity of increasing the efficiency of private employment agencies in this regard. They stated that socioeconomic development is destroyed because of the inadequacy of labor market institutions and information systems. The areas of discussion included the desire to introduce effective vocational training and on-the-job training programs to address the lack of skilled labor; poverty and poverty reduction policies; the need for the establishment of social protection systems, national qualification systems, and job security systems; and the establishment of electronic tax payment systems to prevent tax losses.

The most intensely debated issue in the Arab States region was “working conditions and the fragility (vulnerability) of local and migrant workers.” Syrian and Lebanese workers and working conditions were among the critical issues. The publications emphasized that participation in the labor force and the skills demanded by the labor market are low. They stated that labor costs and inputs are expensive, so the informal sector could not be regulated. Export-oriented sectors stood out because of oil revenue, but other sectors lagged behind. Psychosocial support service providers have been increasing in recent years. The ILO articles emphasized that agrochemical products were concentrated in the region, that production costs and greenhouse production were increasing. They also emphasized the importance of health insurance and that the government provides many supports such as technical support, business support packages, childcare supports, and financial support. Looking toward the future, the articles said that labor market capabilities should be developed through on-the-job learning in line with digital capabilities even though informality has increased because of home-based work.

After we completed the regional analysis, we made another analysis using the same data, this time looking individually at the 5 quarters covering January 2020 to April 2021.

In the first of the 5 quarters covering the selected COVID-19 pandemic period, the ILO publications extensively discussed the issue of informal labor on a global scale. “Decent work, vulnerable workers, and social dialogue” were the hot topics of discussion. Health institutions and the activities of social protection, assistance, and security were among the priority issues, and the discussion of measures taken for the protection of workers intensified over this period. This quarter’s publications emphasized that for the continuation of labor demand, government-based income supports and measures to increase the workforce’s productivity should be taken.

Discussions on “working conditions and social protection measures” gained momentum in the second quarter. The health sector and occupational diseases came to the forefront again within the framework of international labor standards. The publications suggested that social protection systems should be combined with labor laws and new structures should be formed. They emphasized financial measures, including wage protection, and the need to strengthen public employment services. The need to strengthen technical and income support was also among the priorities discussed. Measures against destruction, especially in the tourism sector, were also among the reports of the period.

“Working conditions and intensified informal labor” were the prominent themes of the third quarter. Unlike the previous quarters, child labor was also on the agenda. Labor rights, active labor market policies, and social protection measures maintained their importance. Discussions around the problems of the supply chain in food services began during this quarter. In addition, the articles emphasized that digital capabilities should be strengthened in order to continue the business process. While the concept of decent work kept its agenda in this quarter, job losses and wage protection began to gain importance.

“The destruction of international labor standards in the context of decent work” stood out in the fourth quarter. Many articles mentioned that for a country to have a sustainable development process it must create national polices to target unregistered employment. The publications stated that social protection systems should be combined with active labor market policies, and the workforce should be protected. While the articles generally emphasized the need to create new jobs at the national level, they also mentioned minimum wages and generally low wage levels.

In the fifth quarter, the ILO’s use of the phrase “decent work and working conditions” increased, especially within the scope of remote work. The articles stated that national employment policies were gradually deteriorating in the face of international labor standards and that employee productivity had decreased while unregistered employment had increased. Some articles addressed social protection systems and their implications for sustainable growth, as well as how data collection and analysis has increased with the growth of social security systems. There were also many reports that business continuity was a prominent problem in this quarter in particular.

This article aims to reveal the most intensely discussed themes in the publications originating from the ILO’s regions during the COVID-19 pandemic period.

We gathered themes under four main headings within the scope of the ILO regional separation and the limitation of the 5-quarter period (January 2020–April 2021). (Additional figures are available under "source data.") These themes are “regulations/interventions,” “labor relations,” “vulnerabilities,” and “education/training.”

The intensities of the regional discussion themes were as follows:

· Americas: working hours, labor rights, labor laws

· Europe and Central Asia: local workers, working-age population, migrant and working conditions

· Asia and Pacific: migrant workers, vulnerable workers, forced labor

· Africa: informal economy, skills development, work permits

· Arab States: working conditions, local/migrant workers, vulnerable workers.

The periodic theme intensities were as follows:

· First quarter: informal workers, decent work, vulnerable workers

· Second quarter: working conditions, lockdown measures, social protection measures

· Third quarter: working conditions, informal economy workers, vulnerable workers

· Fourth quarter: decent work, international labor standards, national policy

· Fifth quarter: decent work, working conditions, remote work.

We mostly see supports and interventions under the heading of “regulations/interventions.” Many articles in this heading deemed it necessary to build a set of rules, especially to address the unique dynamics of digital labor markets. The articles also expressed that the prevalence of remote work necessitates a total restructuring of institutional arrangements. They suggested that there is a need for specially structured recommendations, contracts, and laws regarding a new working order, even though a great deal has been made in the global context since the industrial era on issues such as fundamental rights, working hours, and occupational health and safety. New tax policies seem to be discussed alongside social security systems. Many reports stated that there is a need for a new structure regarding tax collection systems and tools. In summary, regulations are commonly discussed in this theme title.

Under the classification of “labor relations,” we find that statements to strengthen employment relations within the scope of social dialogue are predominant. Social dialogue includes healthy relations between the parties and reveals a new area of negotiation within the scope of decent work. The documents reported that there is a need for new forms of organization to protect and develop the rights of the workforce formed by the new working styles. Unions could compensate for the worsening situation, especially in the case of enchroachment on the fundamental rights and benefits of workers who use digital labor platforms. However, the rapid evolution of the traditional structure of trade union organizations is not easy. That is not to say that unions are unprepared, as the publications stress that unions are aware of the transformation dynamics accelerated by the pandemic. In the country reports examined, we see that there was an effort to develop job and worker databases. Although the reports stated that the databases were primarily structured to create new employment opportunities or to keep the social security system under control, the databases could also help establish an infrastructure for new trade union organizing. Many reports emphasized that there may be significant problems in today’s traditional structure, especially in the organization of gig workers and contractors. Inside the ILO publications, there were statements that the loss of rights resulting from digital and remote work significantly damages the concept of decent work that the ILO has emphasized for years, statements that new measures should be taken to protect the scope of decent work, and statements that indicate that decent work standards are rapidly deteriorating in many countries. In summary, the main theme of the classification of “labor relations” is the concepts of social dialogue, employment relationships, and decent work.

Under the “vulnerabilities” classification, we interprete themes for disadvantaged groups and those who lost their jobs during the pandemic and had difficulty finding new jobs. The ILO articles touched on the subjects of refugees, youth, children, the elderly, and the disabled, especially women. The reports stated that the invisible labor burden of women (for example, responsibilities such as housework and the care of children, elderly, and disabled people) has increased even more. The publications also emphasized that with the increase in the invisible labor burden of women, women’s employment is in danger of shrinking, a situation that would negatively affect gender equality in working life. In the documents examined, we see that the subjects were mainly informal employment, lack of income, working hours, and unemployment. There were also determinations that the number of vulnerable people was increasing as a result of the employment gradually turning into underemployment.29 Unemployment, which occurs at different levels with the deterioration of the balance of labor markets, has came to the fore as an area that all countries focus on for a solution. Because of the support of governments, informal employment can decrease, however this decrease did not seem to apply to refugees in informal employment. From the widespread mentions of informality, we see that the problem of informality has now become a worldwide problem. Informal employment risks were higher in developing countries because of their relatively low capacity to provide substantial financial support to the labor market. The works we classified under “vulnerabilites” also pointed out that the millions of workers who have shifted to digital platforms have become more vulnerable generally.

To increase accuracy, we separate informality into different dimensions of the workforce. Although the general global statistical trend shows that the working poverty rates have decreased, we understand from the examined publications that working poverty has become more prominent because of the pandemic and the sudden shift to remote work. From the sheer amount of mentions of working poverty we see in the documents we analyzed, we would not be surprised if the global poverty rates stopped decreasing and started to increase. The publications saw a rise in investigations of working poverty at the same time as they saw a rise in the investigations of the remote and gig work. There were statements that members of the labor force, especially those working remotely, were at risk of becoming the working poor. In summary, the “vulnerabilities” classification comprises the concepts of disadvantaged groups (women, refugees, youth, children, the elderly, and the disabled), migrant workers, informal employment, unemployment, and working poverty.

In the “education/training” classification, articles emphasize the importance of training, and most reports contain statements about distance education. The publications noted that some trainings, such as occupational health and safety training, technical training, or new-employee training, could be provided more cost effectively and efficiently online than in person. The analyzed reports stated that it will be possible for the scope of lifelong learning to be more effective thanks to distance education and that many measures have been taken in this regard. Many articles posited that new training programs should be created to replace traditional vocational education institutions. These reports show that throughout the pandemic businesses are rethinking how to deliver training to employees. We see that the publications gave special attention to the on-the-job and vocational training of young people who often face higher levels of unemployment. There were also recommendations for the national qualification system establishment. Since physical distance matters less now because of digitalization, the determinations that the workforce should be equipped with global skills were also noteworthy. In summary, the main theme of the education/training classification is the concepts of talent, business development, skills and vocational training in particular and also lifelong learning and online education in general.

To summarize, the main theme “regulations/interventions” includes interventions such as government measures, social services, supporting income/enterprises/wages/technical, public employment services, active labor market policies, labor market institutions, labor protection, social security, social dialog, and social policy. The “labor relations” theme comprises decent work, labor standards, employment relationships, employment contracts, labor force participation, remote work, and unemployment. “Vulnerabilities” covers topics such as refugee/migrant child, youth, gender discrimination, informal workers, working conditions, and working hours. Finally, the “education/training” theme contains topics such as technical, skill and vocational training, skills development, capacity development, digital skills, and national qualification system.

We find in these articles and reports that vulnerable populations, working conditions, wages, trade unions' rights, working poor, occupational health and safety, social security and dialogue have shaped the bulk of the research surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. More research will be needed to see if these themes continue in the postpandemic environment.

M. Çağlar Özdemir, Hakan Mete, Cihan Selek Öz, and V. Çağrı Arik, "Global labor market debates in the ILO publications in the COVID-19 era," Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, September 2023, https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2023.20

1 Thereza Balliester and Adam Elsheikhi, “The future of work: a literature review,” Working Paper 29 (International Labour Organization, March 2018), https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---inst/documents/publication/wcms_625866.pdf.

2 Dominique Méda, “The future of work: the meaning and value of work in Europe,” Research Paper 18 (International Labour Organization, October 2016), https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---inst/documents/publication/wcms_532405.pdf. See also “A just transition for all: can the past inform the future?,” editorial, International Journal of Labour Research, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 173–185, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---actrav/documents/publication/wcms_375223.pdf.

3 Stephen Hughes and Nigel Haworth, The International Labour Organization (ILO): Coming in from the Cold, (New York: Routledge, 2011).

4 Guy Standing, “The ILO: an agency for globalization?,” Development and Change, vol. 39, no. 3 (May 2008), pp. 355–384, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2008.00484.x.

5 Miriam A. Cherry, “Back to the future: a continuity of dialogue on work and technology at the ILO,” International Labour Review, vol. 159, no. 1, March 2020, pp. 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12156.

6 Decent Work (Report of the Director-General), International Labour Conference, 87th session (Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office, June 1999), https://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc87/rep-i.htm.

7 International Labour Organization, “A just transition for all," pp. 173–185.

8“The role of public employment programmes and employment guarantee schemes in COVID-19 policy responses” Development and Investment Branch (DEVINVEST), May 29, 2020, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_746368.pdf.

9 ENTERPRISES Department, “COVID-19 and enterprises briefing note [no. 1]” (International Labour Organization, March 20, 2020), http://spf.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_740955.pdf.

10 ENTERPRISES Department, “COVID-19 and ENTERPRISES briefing note [no. 2]” (International Labour Organization, March 23, 2020), https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_740957.pdf.

11 ENTERPRISES Department, “COVID-19 and ENTERPRISES briefing note [no. 3]” (International Labour Organization, March 24, 2020), https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_740958.pdf.

12 ILO Decent Work Team South Asia and India, “Short-term policy responses to COVID-19 in the world of work” (International Labour Organization, March 30, 2020), https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_739454.pdf.

13 “Decent work indicators: guidelines for producers and users of statistical and legal framework indicators” in ILO Manual (International Labour Organization, December 2013), https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---integration/documents/publication/wcms_229374.pdf.

14 ILO Decent Work Team South Asia and India, “Short-term policy responses to COVID-19 in the world of work.”

15 Lode Godderis, “Good jobs to minimize the impact of COVID-19 on health inequity,” International Labour Organization, April 20, 2020, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---safework/documents/publication/wcms_742059.pdf.

16 “Coping with double casualties,” DEVINVEST.

17 See the official International Labour Organization website at https://www.ilo.org.

18 The columns of the Excel table created in this way consist of the date of publication of the data (date issues), primary type of data (publication), secondary type of data (for example, report within publication or publication within publication), number of pages, tags, regions and countries covered, the first title of the data (title 1), the second title of the data (title 2), internet connection address (link-web), and the PDF file download address (link-download).

19 David R. Thomas, “A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data,” American Journal of Evaluation, vol. 27, no. 2, June 2006, pp. 237–246, https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748.

20 Rachel Ormston, Liz Spencer, Matt Barnard, and Dawn Snape, “The foundations of qualitative research,” in Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, eds. Jane Ritche, Jane Lewis, Carol McNaughton Nicholls, and Rachel Ormston, 2nd ed. (Los Angeles, California: Sage, 2014).

21 Grounded theory is a qualitative approach with dynamics. This method was introduced in the 1960s as part of a sociological research program on death in hospitals. See Barney G. Glaser and Anselm L. Strauss, The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (Chicago: Aldine Transaction, 1967). Grounded theory emerged in an effort to discover the root causes of an event beyond the apparent empirical evidence. For example, see Juliet M. Corbin and Anselm Strauss, “Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria,” Qualitative Sociology vol. 13, no. 1, 1990, pp. 3–21, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593. Although grounded theory is a qualitative method, it effectively reveals the truth by blending the strengths of quantitative methods with qualitative approaches. See Kathy Charmaz, “Grounded theory: objectivist and constructivist methods” in Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds. Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage, 2000). In this context, it can be defined as the whole of the systematic analysis process inherent in quantitative survey research, with combined logic, rigour, and the depth and richness of qualitative interpretative traditions. See Barbara Keddy, Sharon L. Sims, and Phyllis Noerager Stern, “Grounded theory as feminist research methodology,” Journal of Advanced Nursing vol. 23, no. 3, March 1996, pp. 448–453, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb00005.x. See also Linda C. Robrecht, “Grounded theory: evolving methods,” Qualitative Health Research vol. 5, no. 2, May 1995, pp. 169–177, https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239500500203.

Grounded theory is a methodology that starts with data collection and then derives insight from the systematically collected data. See Ian Dey, Grounding Grounded Theory: Guidelines for Qualitative Inquiry (Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 1999). In grounded theory, first researchers identify an area they would like to research. Next, they determine the scope of data about the theme, and then they find, code, and systematically analyze the data. Once the data are examined, the researchers then develop and test a hypothesis. In the first stage of coding and analysis, called "manual coding", analysts code independently from each other and create a theoretical infrastructure for the data. Next, researchers segment, compare, and categorize the data. At this stage, researchers use inductive and reductive thematic analytical processes to determine similarities and differences between items, and new categories are created. (In this context, inductive means reaching from data to facts and then from facts to theme and main idea. Reductive means taking a large dataset and streamlining it to its core components. For more information, see Corbin and Strauss, “Grounded theory research.”) Then the generated structure can be subjected to a more advanced analysis tool, and automatic coding can be used. Thanks to the chains of relationships structured within the data, it is possible to reveal the embedded theory about the researched subject as a result of the analysis. This inference also helps to compare scattered data in context. See Diane Walker and Florence Myrick, “Grounded theory: an exploration of the process and procedure,” Qualitative Health Research, vol. 16, no. 4, April 2006, pp. 547–559, https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305285972.

22 For an account of the history of computer-aided qualitative data analysis software and a reflection on its role in science, see FC Zamawe “The implication of using NVivo software in qualitative data analysis: evidence-based reflections,” Malawi Medical Journal, vol. 27, no. 1, March 2015, pp. 13–15, https://doi.org/10.4314%2Fmmj.v27i1.4.

23 For more information, see Christina Silver and Ann Lewins, Using Software in Qualitative Research: A Step-by-Step Guide (Sage, 2014), https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473906907.

24 The regions correspond with the regions defined by the ILO. A complete list of which countries appear in which region can be found at https://ilostat.ilo.org/resources/concepts-and-definitions/classification-country-groupings/.

25 The 22 words are as follows: workers, labour, ILO, social, COVID, employment, sector, enterprises, gender, income, job, decent, interventions, poverty, education, training, trade, youth, entrepreneurship, digital, OHS (occupational health and safety), and government.

26 This technique is called "word tree analysis ±3."

27 A “close component” is any of the words, related phrases, sentences, and paragraphs that are the subject of the analysis.

28 We emphasize that measures for social protection are not only for workers but also for employers.

29 Underemployed workers are those who are not working to their full potential at a full-time job (for example, a worker with a PhD working at a job that does not require one) or who would like to work full time but have to work part time only.