An official website of the United States government

United States Department of Labor

United States Department of Labor

Crossref 0

The Changing Pattern of Stock Ownership in the US: 1989–2013, Eastern Economic Journal, 2018.

The impact of an employer match and automatic enrollment on the savings behavior of public-sector workers, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 2023.

Reimagining the Monthly Review, July 1915, Monthly Labor Review, 2016.

What happens to workplace pension saving when employers are obliged to enrol employees automatically?, International Tax and Public Finance, 2020.

Automatic Enrollment and Its Relation to the Incidence and Distribution of DC Plan Contributions: Evidence from a National Survey of Older Workers, Journal of Consumer Affairs, 2019.

This article uses restricted-access employer-level microdata from the National Compensation Survey to examine the relationship between automatic enrollment and employee compensation in 401(k) plans. By boosting plan participation, automatic enrollment can increase employer defined contribution (DC) plan costs, as previously unenrolled workers receive matching contributions. Using information on the cross-sectional variation in employer compensation costs and the automatic enrollment provision of firms sponsoring DC plans, we examine differences in worker compensation between establishments with and without the provision. A statistically significant negative correlation exists between the generosity of the employer match structure and the automatic enrollment provision. However, we find no evidence that total compensation costs or DC costs differ between firms with and without automatic enrollment, and no evidence that DC costs crowd out other forms of compensation.

The dramatic rise of employer-sponsored defined contribution (DC) plans in the United States has been accompanied by an increasing concern about the retirement security that these plans provide. While the majority of workers choose to participate in a DC plan if offered one, many—particularly low-wage employees—fail to sign up.1 Moreover, contribution rates among participants are relatively low, and many workers do not contribute enough to take full advantage of their employers’ match.2

To encourage participation, employers are increasingly automatically enrolling new employees while allowing them to opt out. Some research suggests that the popularity of the automatic enrollment provision increased after the passage of the Pension Protection Act (PPA) of 2006, which removed many of the legal barriers to automatically enrolling eligible employees into DC plans.3 A number of studies have documented significant increases in retirement plan participation rates within firms that instituted automatic enrollment.4 Yet, we do not have a complete understanding of how the increase in participation rates is accommodated by the labor market.

According to standard economic theory, profit-maximizing employers operate at the point where the marginal product of labor equals the marginal cost. Since a common way for firms to encourage workers to participate and contribute to retirement plans is to match some percentage or dollar amount of worker contributions,5 automatic enrollment likely increases employer costs. This increase occurs because, all else equal, previously unenrolled workers begin receiving matching employer contributions upon automatic enrollment.

To restore equilibrium and offset the extra costs associated with automatic enrollment, employers could adjust the provisions of their 401(k) plans or any of the nonretirement components of their compensation packages. However, if automatic enrollment increases productivity—either directly (by affecting the production function of labor and resulting in a positive marginal revenue or cost savings) or indirectly (by increasing the marginal product of labor)—then some of the gains might be passed to employees in the form of higher employee compensation. Thus, productivity gains resulting from the automatic enrollment provision could also result in an equilibrium where opt-out 401(k) packages are associated with higher total compensation costs than are packages with an opt-in mechanism. Moreover, the change in total compensation need not affect all components of compensation the same way. Changes in total compensation might translate into changes in wages; health or other benefits; or specific DC plan features, such as the generosity of the plan match structure.

In this article, we offer cross-sectional evidence on the ways in which compensation packages for workers with 401(k) plans differ between firms with and without automatic enrollment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first article to address this question. In addition, we use a nationally representative dataset of employers, which provides information not only on the specific characteristics of the DC plans offered (characteristics such as match generosity and automatic enrollment) but also on the full set of items composing the total compensation package. We use restricted-access microdata from the National Compensation Survey (NCS), which does not suffer from the measurement and misreporting errors on employee benefits that are commonly observed in household surveys.6

Our results confirm previous findings that plans with automatic enrollment have, on average, higher participation rates. However, we find no evidence that total compensation costs statistically differ between firms with and without automatic enrollment. In addition, we find no evidence (1) that DC costs of employers with opt-out 401(k) plans are any different from those of employers with opt-in 401(k) plans or (2) that automatic enrollment results in a crowding-out effect between DC costs and other forms of compensation. Finally, we do find that plans with automatic enrollment offer match rates that are, on average, 0.38 percentage point (or 11 percent) lower than the rates of plans without automatic enrollment, even when we control for other characteristics. Given the average wage, participation, and match rates of the plans in our sample, this translates into a savings of roughly 7 cents per labor hour, which offsets the additional costs of 6.5 cents resulting from higher participation in autoenrollment plans.

The article is organized into six main sections. The next section provides background information on DC plans and automatic enrollment. The two sections that follow describe the data and present descriptive statistics. The section after that explains our empirical strategy and discusses the results. The last two sections provide a discussion and a conclusion.

The pension landscape in the United States has been gradually shifting, with employers moving away from offering defined benefit (DB) pension plans to their employees toward offering DC plans. The rise in DC plans has introduced features, such as voluntary participation, not usually present in DB plans. In typical DB plans, employees are automatically enrolled and cannot opt out. In most DC plans, employees must elect to participate, even though this requirement is slowly changing. As a result, in 2014, the participation rate among private wage and salary workers who were offered an employer retirement plan was 88 percent in DB plans and only 68 percent in DC plans.7

Employees who are offered plans yet choose not to participate receive the most attention from policymakers. Not only are these workers not taking advantage of tax-deferred opportunities to save for retirement, but many are giving money away by not taking advantage of their employers’ matching contributions. Recognizing that automatic enrollment can increase participation in DC plans and thereby increase retirement savings, the U.S. Treasury Department authorized employers to adopt autoenrollment in 1998 for new hires and again in 2000 for previously hired employees not already participating in their employers’ plans.8

In addition, employers are concerned about employees who do not enroll in 401(k) plans, because these employees jeopardize the company’s performance on nondiscrimination tests—that is, rules forbidding employers from providing benefits exclusively to highly paid employees. By increasing participation among nonhighly compensated employees, automatic enrollment makes it possible for employers to raise or eliminate contribution limits on highly compensated employees, effectively increasing their pension benefits.9 In fact, one-fifth of plan sponsors said that improving the results of nondiscrimination tests was their primary motivation for offering automatic enrollment.10

Automatic enrollment (also known as negative election or an opt-out mechanism) is a 401(k) plan feature in which elective employee deferrals begin without requiring the employee to submit a request to join the plan. When automatic enrollment is present, employees who do not select a contribution amount have a predetermined percentage of their pay deferred as soon as they become eligible for the plan. If employees do not want to participate, they must request to be excluded from the plan.

Several studies and anecdotal accounts suggest that automatic enrollment has succeeded in dramatically increasing 401(k) participation.11 Brigitte Madrian and Dennis Shea, for example, document a 48-percentage-point increase in 401(k) participation among newly hired employees and an 11-percentage-point increase in participation overall at one large U.S. company over a period of 15 months after the adoption of automatic enrollment.12 The authors also note that automatic enrollment has been particularly successful at increasing 401(k) participation among employees least likely to participate in retirement savings plans—namely, employees who are young, lower paid, black, or Hispanic.

Various sources point to the increasing popularity of automatic enrollment plans since the passage of the PPA.13 A number of cost, fiduciary, and tax incentives in the PPA have been identified as likely drivers of employers’ increased willingness to adopt various automatic provisions, including automatic enrollment, in their 401(k) plans.14

Some studies have suggested that instituting automatic enrollment might indeed be associated with higher costs. A 2001 report outlining the benefits and costs of adopting automatic enrollment noted that the largest expense related to autoenrollment is “the money needed to fund any employer match for new enrollees.”15 The same report also noted that, aside from the extra costs of an employer match, firms adopting automatic enrollment are likely to incur additional costs from maintaining and servicing a large number of small accounts, especially if autoenrollment is extended to all eligible employees. According to one survey, 73 percent of employers who were unlikely to adopt autoenrollment cited the increased cost of the employer match as a major barrier to such adoption.16 Sure enough, the majority of plans that automatically enroll employees do this only for new hires. Another survey also found that, in 82 percent of plans, autoenrollment was used only for new hires.17 There is some evidence that because of their desire to minimize match contributions and other plan-related costs, employers are reluctant to “backsweep” existing nonparticipants.18 At the very least, this evidence suggests that, as profit maximizers, most firms will not passively accept the higher employee compensation costs that may be associated with automatically enrolling workers.

We can analyze the effects of automatic enrollment from the point of view of the employer by first decomposing labor compensation costs into their components. Total compensation costs (TC) per labor hour can be written as the sum of defined contribution costs (DC) and nondefined contribution costs (NDC), where all costs are a function of automatic enrollment, denoted by a. One could think of a as a binary indicator of the presence of automatic enrollment or as a continuous measure between 0 and 1 that varies with the share of employees the firm automatically enrolls (automatic enrollment is based on job characteristics such as tenure, income, and so on).

Total costs are given by

![]()

Then, the effect of changes in a on total compensation can be expressed as

![]()

In addition, defined contribution costs are a function of participation rates (partic), match generosity (m), employee contribution rates (contrib), and wages (w):

![]()

Taking the first derivative of equation (3) with respect to a and substituting the result into equation (2) gives us

Our empirical specifications focus on estimating the components of equation (4). Since previous literature has documented that participation rates increase (at least in the short term) after the implementation of automatic enrollment, we can sign the first term on the right-hand side of equation (4). Holding all other factors constant (i.e., assuming the last four terms on the right-hand side of equation (4) are zero) suggests that the adoption of automatic enrollment increases employer DC plan costs, and therefore total costs, because of the increase in participation ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Previous studies have already discussed some of the levers that employers can use in dealing with the costs of automatic enrollment. As Mauricio Soto and Barbara Butrica note, employers can (1) reduce the generosity of the match offered to participating workers (the second term on the right-hand side of equation (4)); (2) reduce compensation other than pension benefits (the fourth and fifth terms on the right-hand side of equation (4)) to keep total compensation at the level maintained before the introduction of the autoenrollment feature; or (3) leave the pension and other compensation arrangements unchanged or even increase compensation if automatic enrollment raises productivity.19

In their empirical analysis, Soto and Butrica examine the relationship between automatic enrollment and employer contributions or match rates. While the authors’ results suggest that automatic enrollment might be associated with lower employer match rates, the only other study that has examined a similar relationship—a study by Jack VanDerhei20—contradicts these results. VanDerhei reports higher effective employer match rates in 2009 than in 2005 among employers that adopted automatic enrollment. Both studies, however, have their shortcomings. Because Soto and Butrica relied on cross-sectional data, they were unable to examine changes in employer match rates after the adoption of automatic enrollment. Data limitations also prevented them from separately identifying the effects of autoenrollment on employees’ elective deferrals and on the plans’ match structure. As a result, the authors managed to capture only the combined effect of the second and third terms on the right-hand side of equation (4). While VanDerhei was able to observe match generosity in the same plans in 2005 and 2009, his estimates were based on a sample of large 401(k) plans, which were not necessarily nationally representative. Moreover, neither study examined the relationship between automatic enrollment and total DC plan costs, and no previous study has examined the correlation between automatic enrollment and non-DC costs or total compensation costs. Although our study also relies on cross-sectional data, the NCS is nationally representative and allows us to examine all components of total compensation (including the employer match generosity) and their relation to automatic enrollment.

Another way to keep costs down, and one not identified in Soto and Butrica’s study, is for employers to set a low default deferral rate (the third term on the right-hand side of equation (4)). When instituting automatic enrollment, employers must choose a default contribution rate for employees who do not select a contribution rate or level.21 Although workers can change their contribution rate, studies have shown that automatically enrolled employees tend to remain with the default options of their plans. Madrian and Shea have reported that, at least in the short run, only a small fraction of automatically enrolled 401(k) participants elect a contribution rate or asset allocation that differs from the company-specified default.22 In addition, another study found that automatic enrollment leads to lower contribution rates, as participants who would have voluntarily saved at a higher rate remain at the lower default contribution rates.23 The same study also found that the default contribution rate under automatic enrollment does not affect employees’ decisions to quit the plan. Thus, a potential way for firms to offset the higher match-related costs created by higher participation rates under automatic enrollment is to set low default contribution rates. In the empirical section of the article, we compare the default contribution rates in plans with automatic enrollment with the contribution rates at which workers would maximize their employer match.

We use restricted microdata from the NCS, a large, nationally representative survey conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The NCS collects compensation and benefits information from establishments and covers civilian workers in both private and government industries.24

The NCS collects employer-level data on establishment size, region, and industry. It also collects job-level information on unionization; percentage of full-time workers; occupation; participation in retirement plans; the incidence of benefits and provisions of benefit plans, such as insurance (life, short-term disability, and long-term disability), paid leave (sick, vacation, jury duty, personal, and family), and paid holidays; and detailed provisions (provided in plan brochures) of healthcare plans (medical, dental, vision, and prescription drugs) and retirement plans (defined benefit and defined contribution). Pension plan-level data on plan type, match structure, match rates, and automatic enrollment are also collected.

The NCS also collects information on employer costs, including wages and salaries and costs for a variety of employee benefits, such as paid leave, health insurance, and retirement. Each benefit cost is averaged across workers in a particular job, even though there may be some variation among workers within the job in take-up of or eligibility for the benefit. Similarly, wages are averaged across workers in a particular job, and the averaging obscures intrajob wage variation.25

For our analysis, we use NCS data for 2009–2010. Since our goal is to examine the correlation between automatic enrollment and the components of DC costs and other compensation costs, our sample restrictions are driven by the availability of detailed information on plan characteristics. Our sample includes savings and thrift plans, as these are the only types of plans for which BLS collects information on both the automatic enrollment provision and the match structure. We exclude “zero-match” plans from our sample, because BLS does not consider these plans to provide employee benefits and therefore does not collect data about their features.26 To the extent that employers with zero-match plans are more likely to implement automatic enrollment (since they face close to no change in cost), excluding them from our sample could bias upward the coefficient on automatic enrollment in the regression of match generosity. If so, the estimated negative correlation between automatic enrollment and employer match rates in our empirical section can be viewed as a conservative upper bound. We also exclude plans (mostly money-purchase or profit-sharing plans) for which the employer contributes without requiring minimum employee contributions, because BLS does not collect automatic enrollment information for these plans. We further restrict our sample to plans with flat match structures—that is, plans in which a percentage is applied to employees’ contributions up to a specified percentage of the employees’ salaries—since BLS collects detailed information on the match structure of only these plans.

Overall, 51 percent of workers in the full NCS sample have a DC plan. Among those, 76 percent have a savings and thrift plan, and 69 percent of workers with such a plan have a flat match structure. After dropping some duplicate records, our final sample includes roughly 3,800 job-level observations uniquely identifying about 1,200 savings and thrift plans with flat match structures.

In our analysis, the key variables of interest are the match rate, the match ceiling, the maximum match rate, the default contribution rate, the default match rate, an autoenrollment indicator, DC costs, and other compensation-cost variables. (See table 1.) The maximum match rate is determined by the match rate (i.e., the percentage of each dollar of employee contributions that is matched) and the match ceiling (i.e., the limit on the percentage of contributions that are matched). Workers who contribute up to the match ceiling receive the maximum employer match. For example, if a 401(k) plan has a match rate of 50 cents per dollar up to a ceiling of 6 percent of pay, the maximum match rate is 3 percent of pay.

| Generosity measure | Unit of measurement | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Plan provisions | ||

| Match rate | Integer from 0 to 100 | The percentage of each dollar of employee contributions that is matched (e.g., 50 cents on the dollar or 50 percent). |

| Match ceiling | Integer from 0 to 100 | The limit on the percentage of employee contributions that is matched (e.g., employee’s contribution is matched up to 6 percent of pay). |

| Maximum match rate | Integer from 0 to 100 | Maximum employer contribution as a percentage of salary. Alternatively, the percentage of salary that the employer would contribute if the employee contributed enough to exhaust the employer’s match offer. This variable is computed as (match rate*match ceiling)/100. |

| Default contribution rate | Integer from 0 to 100 | In plans with automatic enrollment, the default employee contribution percentage. |

| Default match rate | Integer from 0 to 100 | This variable is computed as (match rate*default contribution rate)/100. |

| Default maximum contribution rate | Integer from 0 to 100 | In plans with automatic enrollment, the default employee contribution percentage at the end of the escalation process. |

| Default maximum match rate | Integer from 0 to 100 | This variable is computed as (match rate*default maximum contribution rate)/100. |

| Employer average cost for providing benefits to workers in a given job | ||

| DC costs | $ per labor hour | Includes all DC plans. |

| Wages | $ per labor hour | Includes wages. |

| Health insurance costs | $ per labor hour | Includes health insurance. |

| Legal costs | $ per labor hour | Includes Social Security, Medicare, state and federal unemployment insurance, and worker’s compensation. |

| Leave costs | $ per labor hour | Includes vacation, holidays, sick leave, and other leave. |

| Insurance costs | $ per labor hour | Includes life insurance and short-term and long-term disability. |

| Other costs | $ per labor hour | Includes nonproduction bonuses, severance pay, and supplemental unemployment insurance. |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey, Employer Costs for Employee Compensation data. | ||

In plans with automatic enrollment, the default contribution rate is the percentage of the worker’s salary that is deferred if the worker does not select a contribution rate. The default match rate is similar to the maximum match rate but computed on the basis of the default contribution rate instead of the match ceiling. It is the percentage of salary that the employer contributes if a worker remains at the default contribution rate. Some plans with automatic enrollment also have escalating employee default contribution rates. Thus, the default maximum contribution rate and the default maximum match rate are reached at the end of the escalation.

In the descriptive analysis, we use job-level weights to reflect the percentage of workers in the private sector who have jobs with a DC plan of particular characteristics.

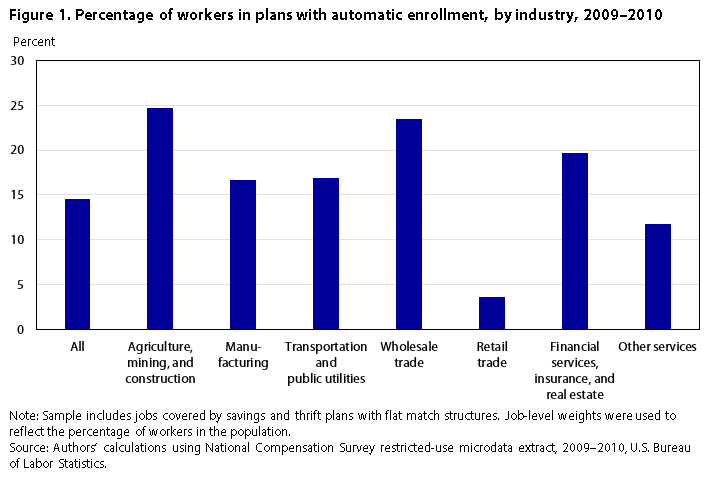

| Industry | Percentage of workers |

|---|---|

| All | 14.5 |

| Agriculture, mining, and construction | 24.7 |

| Manufacturing | 16.6 |

| Transportation and public utilities | 16.9 |

| Wholesale trade | 23.5 |

| Retail trade | 3.6 |

| Financial services, insurance, and real estate | 19.7 |

| Other services | 11.8 |

| Note: Sample includes jobs covered by savings and thrift plans with flat match structures. Job-level weights were used to reflect the percentage of workers in the population. Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | |

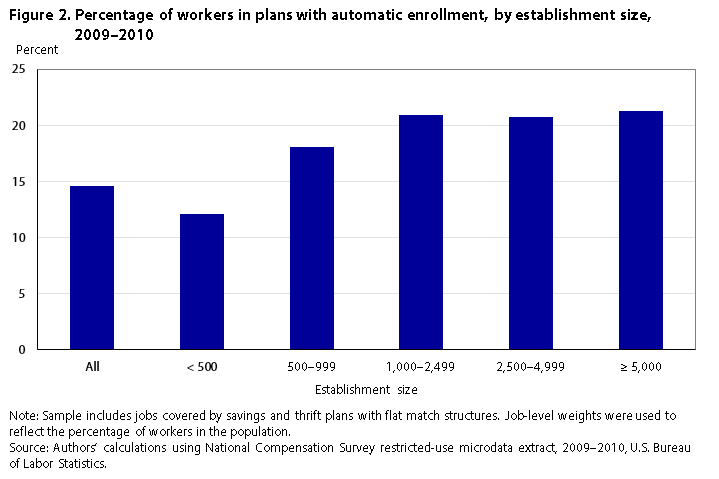

| Establishment size | Percentage of workers |

|---|---|

| All | 14.5 |

| < 500 | 12.1 |

| 500–999 | 18.1 |

| 1,000–2,499 | 20.9 |

| 2,500–4,999 | 20.8 |

| ≥ 5,000 | 21.2 |

| Note: Sample includes jobs covered by savings and thrift plans with flat match structures. Job-level weights were used to reflect the percentage of workers in the population. Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | |

Prevalence of automatic enrollment. In our sample, 14.5 percent of workers with savings and thrift plans have automatic enrollment.27 (See figure 1.) This percentage includes between 20 and 25 percent of workers in agriculture, mining, and construction; wholesale trade; and financial services, insurance, and real estate; however, it represents only about 4 percent of workers in retail trade. The percentage also includes about 1 in 5 workers employed by large firms with at least 1,000 employees, but only 1 in 8 workers in small firms with less than 500 employees. (See figure 2.)

Table 2 shows the distribution of workers with and without autoenrollment plans by establishment characteristic. Compared with workers without autoenrollment plans, those with automatic enrollment are more likely to be employed (1) in agriculture, mining, and construction; wholesale trade; and financial services, insurance, and real estate; and (2) by companies that have 500 or more employees. Those with automatic enrollment are also in establishments (1) with larger shares of workers who have DB pensions and are full time, unionized, and highly paid; and (2) located in metropolitan areas and in the West. For example, 20.3 percent of workers with autoenrollment plans are in the financial services, insurance, and real estate sectors, compared with 14.1 percent of workers with plans without autoenrollment. Also, 43.7 percent of workers with autoenrollment plans are employed by large establishments (500 or more employees), compared with only 30.3 percent of employees who are not autoenrolled. In addition, while 17.7 percent of autoenrolled workers hold unionized jobs, only 4.4 percent of those without autoenrollment do. Finally, only 4.0 percent of workers in firms with autoenrollment have wages in the bottom tercile of the wage distribution, compared with 13.4 percent of counterparts in firms without automatic enrollment.28

| Characteristic | All | Without autoenrollment | With autoenrollment | Statistical difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoenrollment | 14.5 | – | – | – |

| Industry | ||||

| Agriculture, mining, and construction | 4.0 | 3.5 | 6.7 | *** |

| Manufacturing | 15.0 | 14.6 | 17.1 | * |

| Transportation and public utilities | 4.3 | 4.1 | 5.0 | – |

| Wholesale trade | 6.4 | 5.7 | 10.3 | *** |

| Retail trade | 7.6 | 8.5 | 1.9 | *** |

| Financial services, insurance, and real estate | 15.0 | 14.1 | 20.3 | *** |

| Other services | 47.9 | 49.4 | 38.7 | *** |

| Establishment size | ||||

| < 500 | 67.8 | 69.7 | 56.3 | *** |

| 500–999 | 14.0 | 13.4 | 17.3 | *** |

| 1,000–2,499 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 14.8 | *** |

| 2,500–4,999 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 6.7 | ** |

| ≥ 5,000 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 4.9 | ** |

| Share of workers with DB plan | 24.4 | 23.1 | 31.6 | *** |

| Share of full-time workers | 89.0 | 88.1 | 94.1 | *** |

| Share of union workers | 6.4 | 4.4 | 17.7 | *** |

| Wages (tercile) | ||||

| Bottom | 12.0 | 13.4 | 4.0 | *** |

| Middle | 34.0 | 33.7 | 35.9 | |

| Top | 54.0 | 52.9 | 60.1 | *** |

| Metropolitan area | 91.1 | 90.5 | 94.8 | *** |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 20.9 | 21.6 | 16.8 | *** |

| Midwest | 20.5 | 20.3 | 21.5 | – |

| South | 36.9 | 37.5 | 33.3 | ** |

| West | 21.7 | 20.6 | 28.3 | *** |

| Number of observations | 3,802 | 3,052 | 750 | – |

| Note: Sample includes jobs covered by savings and thrift plans with flat employer match structures. Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | ||||

Differences in participation and match rates by autoenrollment. Table 3 compares participation and plan provisions among workers with and without automatic enrollment. Overall, 68.7 percent of workers participate in their employers’ plans. Confirming the findings of previous studies,29 we find that plans with automatic enrollment have a higher participation rate (77.1 percent) than do plans without the feature (67.3 percent).

| Characteristic | All | Without autoenrollment | With autoenrollment | Statistical difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation | Mean | Standard deviation | Mean | Standard deviation | ||

| Participation rate | 68.7 | 26.0 | 67.3 | 26.2 | 77.1 | 23.3 | *** |

| Maximum match rate | 3.5 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 3.2 | 1.4 | *** |

| Match rate | 71.1 | 31.8 | 72.1 | 32.3 | 65.4 | 28.3 | *** |

| Match ceiling | 5.0 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 1.5 | 5.1 | 1.2 | – |

| Default contribution rate | – | – | – | – | 2.8 | 1.1 | – |

| Default maximum contribution rate | – | – | – | – | 3.4 | 1.7 | – |

| Number of observations | 3,802 | 3,052 | 750 | – | |||

| Note: Sample includes jobs covered by savings and thrift plans with flat employer match structures. Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | |||||||

| Industry | Without autoenrollment | With autoenrollment |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, mining, and construction | 3.0 | 2.3 |

| Manufacturing | 3.6 | 2.7 |

| Transportation and public utilities | 3.9 | 2.7 |

| Wholesale trade | 3.4 | 2.8 |

| Retail trade | 4.0 | 2.9 |

| Financial services, insurance, and real estate | 4.5 | 3.8 |

| Other services | 3.1 | 3.4 |

| Note: Sample includes jobs covered by savings and thrift plans with flat match structures. Job-level weights were used to reflect the percentage of workers in the population. Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | ||

| Establishment size | Without autoenrollment | With autoenrollment |

|---|---|---|

| < 500 | 3.4 | 2.8 |

| 500–999 | 3.8 | 3.5 |

| 1,000–2,499 | 3.8 | 4.1 |

| 2,500–4,999 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| ≥ 5,000 | 3.7 | 3.9 |

| Note: Sample includes jobs covered by savings and thrift plans with flat match structures. Job-level weights were used to reflect the percentage of workers in the population. Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | ||

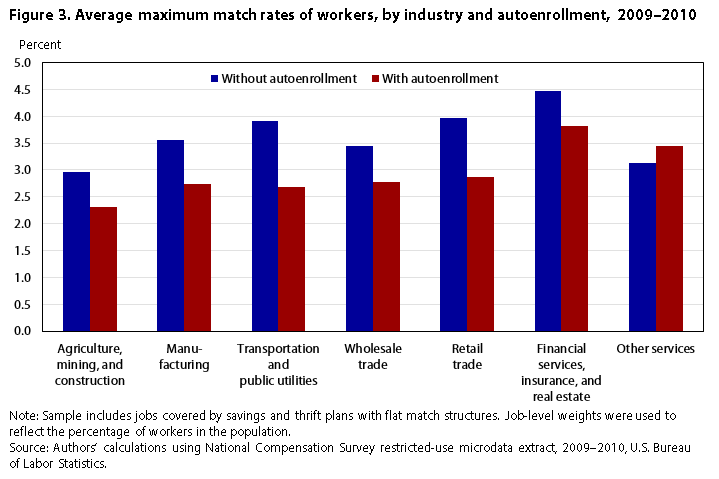

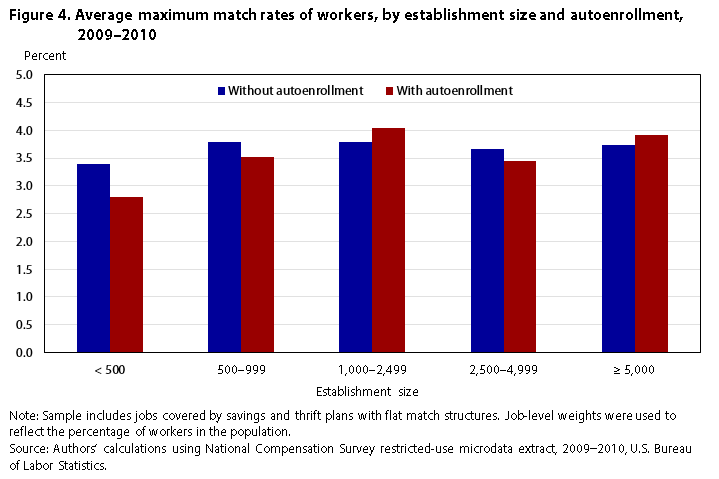

The average match rate is 71.1 percent and differs statistically between workers in plans with and without automatic enrollment (the rates of these workers are 65.4 and 72.1 percent, respectively). The average match ceiling is 5.0 percent of pay and does not statistically differ between workers with and without automatic enrollment. The maximum match rate averages 3.5 percent overall and statistically differs between the two groups of workers; the rate is 3.5 percent for those without autoenrollment and 3.2 percent for those with the plan feature. In most industries examined, average maximum match rates are higher among workers without autoenrollment. (See figure 3.) Group differences are especially large for workers in transportation and public utilities and retail trade. In establishments with less than 1,000 employees and establishments with 2,500–4,999 employees, maximum match rates are also higher among workers without autoenrollment than among those with it. (See figure 4.) However, differences are especially large for workers in establishments with less than 500 employees.

DC plan costs depend not only on how much the employer offers to match, but also on how much workers actually contribute. While we know nothing about employees’ actual contributions, we do know the default contribution rates of plans with automatic enrollment. Previous literature has shown that, once enrolled, workers are slow to move away, if at all, from the defaults.30 If that is the case, the default contribution rate and the resulting default match rate might get us closer to the actual cost of a DC plan than the maximum match rate would.

The average default contribution rate for workers in autoenrollment plans is 2.8 percent. (See table 3.) To receive the maximum match, workers would need to contribute an average of 5.1 percent (the match ceiling). Even with the built-in escalation of the default contribution rate in 22 percent of our plans, the default maximum contribution rate is 3.4 percent. Thus, on average, firms in our sample are defaulting their workers at a contribution rate at which these workers cannot take full advantage of the employer match.

| Match rate | Maximum match rate | Default match rate | Default maximum match rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without autoenrollment | With autoenrollment | |||

| ≤ 2 | 23.69 | 28.75 | 74.73 | 68.22 |

| (2–3] | 31.29 | 36.62 | 21.65 | 21.12 |

| (3–4] | 13.93 | 12.08 | 1.37 | 1.9 |

| (4–5] | 17.36 | 14.72 | 2.25 | 8.77 |

| (5–6] | 11.32 | 6.36 | – | – |

| > 6 | 2.41 | 1.47 | – | – |

| Note: Sample includes jobs covered by savings and thrift plans with flat match structures. Job-level weights were used to reflect the percentage of workers in the population. Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | ||||

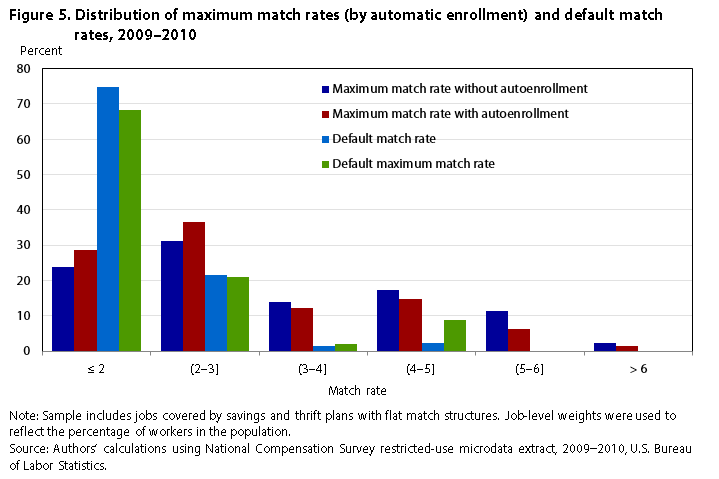

It is informative to examine differences in match structures beyond the mean. Figure 5 compares the distribution of maximum match rates in the two types of plans with the distribution of default match rates and default maximum match rates. Overall, the distribution of the maximum match rate in plans with automatic enrollment is more skewed to the left (i.e., it carries less weight in the right tail) than the distribution in plans without automatic enrollment. The distributions of the default match rate and the default maximum match rate have even less weight in the right tail. Among plans with automatic enrollment, about three-quarters have a default match rate and a default maximum match rate of 2 percent or less of pay; however, less than a third of these plans have a maximum match rate within that range. An even smaller percentage of plans without automatic enrollment have a maximum match rate of 2 percent or less of pay. Thus, in addition to offering lower maximum match rates than the rates offered in plans without autoenrollment, employers with autoenrollment may be using their default employee contribution rate to help offset the higher costs that come with higher participation rates. By setting default match rates lower than maximum match rates, an employer can contribute to the accounts of more workers without necessarily increasing its costs.31

Understanding how establishment costs vary by automatic enrollment. Wages and benefits are higher among workers in savings and thrift plans with autoenrollment than among workers with plans that lack the provision. (See table 4.) For example, among workers with autoenrollment plans, wages average $27.70 per labor hour, health insurance benefits average $3.80 per labor hour, and total costs average $40.90 per labor hour. In contrast, for workers without autoenrollment plans, wages average $26.00 per labor hour, health insurance benefits average $2.90 per labor hour, and total costs average $37.60 per labor hour.

| Variable | All | Without autoenrollment | With autoenrollment | Statistical difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC costs | $1.20 | $1.20 | $1.10 | – |

| Total non-DC costs | 36.90 | 36.40 | 39.70 | *** |

| Total costs | 38.00 | 37.60 | 40.90 | *** |

| Wages | 26.20 | 26.00 | 27.70 | ** |

| DB costs | .50 | .50 | .60 | – |

| Health insurance costs | 3.00 | 2.90 | 3.80 | *** |

| Leave costs | 3.10 | 3.10 | 3.40 | ** |

| Insurance costs | .20 | .20 | .20 | *** |

| Legal costs | 2.80 | 2.70 | 2.90 | *** |

| Other costs | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.10 | – |

| Number of observations | 3,802 | 3,052 | 750 | – |

| Note: Sample includes jobs covered by savings and thrift plans with flat employer match structures. Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | ||||

DC plan costs, unlike match rates and autoenrollment provisions, are not specific to particular plans; instead, they reflect employer costs accrued at the job level.32 For example, DC costs vary by jobs in the establishment, but not by plans within a job. The aggregate measure for these costs is the hourly cost for providing DC plan(s) to workers on a job. Nonetheless, DC costs should be correlated with the maximum match rate, which our results show is statistically lower in autoenrollment plans.33 Furthermore, in addition to the employers’ matching contributions, DC costs include administrative and other expenses that are typically higher in plans with autoenrollment than in plans without the feature.34 However, our descriptive statistics show that DC costs are not statistically different between the two types of plans. (See table 4.)

The descriptive analyses revealed important differences in employer match rates and compensation by automatic enrollment. In the following sections, we examine whether these differences still exist after controlling for other factors.

Automatic enrollment, participation, and the employer match. We begin by examining the relationship between automatic enrollment, plan participation, and the generosity of the employer match. We estimate a series of ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions on plan-level data. The key variable of interest in our models is an indicator for whether a plan includes automatic enrollment features. We report robust standard errors, clustered on the state level.

Table 5 presents results from an OLS regression of plan participation rates on automatic enrollment. Consistent with other studies, we find that the coefficient on automatic enrollment is positive and highly statistically significant.35 Among the savings and thrift plans in our sample, automatic enrollment is associated with participation rates that are 7 percentage points higher. This result is not surprising because the literature on automatic enrollment has consistently and unambiguously reported strong positive effects of automatic enrollment on participation. However, the literature on the effects of the employer match on participation has produced conflicting results. While most studies have found a strong positive link between participation in a retirement plan and the existence of an employer match, the relationship between participation and the level of the match has not been proven to be particularly strong. For example, using a sample of nine firms with automatic enrollment, John Beshears et al. found that reducing the employer match by 1 percent of pay was associated with a decrease of 1.8 to 3.8 percentage points in the plan participation rate at 6 months of eligibility.36 The authors concluded that the presence of an automatic enrollment provision diminishes the need for employers to provide generous matches. In that respect, our results lend support to studies that find positive but only weak effects of the employer match. We find that the maximum match rate is positively correlated with participation, but its coefficient is small and not statistically different from zero.37 Hence, automatic enrollment is a much stronger determinant of participation than the maximum match rate is. This finding supports the hypothesis raised in previous studies, namely, that the importance of the employer match for stimulating participation weakens in the presence of automatic enrollment.38 Finally, some plan provisions in the NCS data have been imputed via a statistical match. We use a flag to control for these imputations and find no statistically significant correlation between the imputed observations and our dependent variables.39

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Standard error | Coefficient | Standard error | |

| Maximum match rate | 0.161 | 0.661 | – | – |

| Default match rate | – | – | .812 | .507 |

| Autoenrollment | 6.990*** | .000 | – | – |

| Industry (omitted = wholesale trade) | ||||

| Agriculture, mining, and construction | -7.887* | .067 | .955 | .893 |

| Manufacturing | -3.927* | .084 | -5.140 | .478 |

| Transportation and public utilities | -1.993 | .584 | 9.909 | .189 |

| Retail trade | -3.380 | .393 | 14.201** | .046 |

| Financial services, insurance, and real estate | 1.745 | .428 | 5.171 | .419 |

| Other services | -4.460* | .063 | 1.481 | .828 |

| Establishment size of 500 or more participants | -.530 | .695 | -3.309 | .317 |

| Share of workers with DB plan | 1.229 | .436 | 3.623 | .267 |

| Share of full-time workers | 18.202*** | .000 | 6.282 | .232 |

| Share of union workers | 2.846 | .323 | -2.080 | .626 |

| Average wage per hour | .226*** | .000 | .219*** | .006 |

| Metropolitan area | -3.888 | .102 | -5.571 | .247 |

| Region (omitted = Northeast) | ||||

| Midwest | -3.707* | .074 | -8.028** | .043 |

| South | -.813 | .405 | -5.646 | .116 |

| West | -3.111* | .082 | -4.216 | .250 |

| Flag for imputed participation | -3.577** | .010 | -7.548*** | .003 |

| Flag for imputed plan | 4.542 | 1.911 | 1.911 | .482 |

| Constant | 54.264*** | .000 | 76.715*** | .000 |

| Adjusted R-squared | .123 | .138 | ||

| Number of observations | 1,193 | 219 | ||

| Note: Sample includes savings and thrift plans with flat match structures. Significance is denoted by Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | ||||

The second model in table 5 shows results from an OLS regression of the relationship between the default match rate and plan participation in plans with automatic enrollment. Although positive, the coefficient on the default match rate is not statistically different from zero and is much smaller than the coefficient on autoenrollment. This result suggests that another way for employers to keep costs down after implementing automatic enrollment is to set a relatively low default match rate, because doing so would not negatively affect participation. This conclusion is also consistent with findings of other studies. For example, William Nessmith et al. found that plan quit rates among employees who had been automatically enrolled in their employers’ retirement plans did not vary in response to changes in the default contribution rate.40 Other factors positively correlated with participation are the average wage per hour and the share of full-time workers.

Next, we estimate the correlation between (1) automatic enrollment and (2) the maximum match rate, the match rate, and the match ceiling. (See table 6.) Results from our OLS regression of employers’ maximum match rate show that the coefficient on automatic enrollment is negative and statistically significant, with a 99-percent confidence level. Controlling for other factors, plans with automatic enrollment have an average maximum match rate that is 0.38 percentage point (11 percent of the average) lower than the rate of plans without the provision. Our findings for the match rate and the match ceiling reveal what is driving this result. The coefficient on automatic enrollment is statistically significant and negative in the regression of the match rate, but it is not statistically significant in the regression of the match ceiling. On average, plans with automatic enrollment have a match rate that is 8.2 percentage points (12 percent of the average) lower than the rate of plans without the feature.

| Variable | Maximum match rate | Match rate | Match ceiling | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Standard error | Coefficient | Standard error | Coefficient | Standard error | |

| Autoenrollment | -0.380*** | 0.009 | -8.262*** | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.925 |

| Industry (omitted = wholesale trade) | ||||||

| Agriculture, mining, and construction | -.206 | .335 | -.767 | .902 | -.155 | .608 |

| Manufacturing | .322 | .272 | -3.939 | .535 | .462* | .090 |

| Transportation and public utilities | .334 | .249 | 6.909 | .262 | -.152 | .597 |

| Retail trade | .358 | .255 | 18.691** | .027 | -.772*** | .004 |

| Financial services, insurance, and real estate | 1.088*** | .000 | 15.173** | .018 | .123 | .541 |

| Other services | -.018 | .938 | 1.658 | .770 | -.500*** | .007 |

| Establishment size of 500 or more participants | 0.206* | .053 | 4.902** | .018 | -.113 | .155 |

| Share of workers with DB plan | .086 | .461 | -4.344* | .069 | .344*** | .002 |

| Share of full-time workers | -.223 | .247 | 1.028 | .774 | -.249** | .034 |

| Share of union workers | -.183 | .307 | -2.400 | .424 | .090 | .612 |

| Metropolitan area | 0.263* | .076 | -2.662 | .328 | .430*** | .007 |

| Region (omitted = Northeast) | ||||||

| Midwest | -.147 | .373 | -1.923 | .590 | -.121 | .317 |

| South | -0.276* | .090 | -4.258 | .217 | -.074 | .568 |

| West | .071 | .624 | -.577 | .859 | .159 | .176 |

| Flag for imputed plan | -.111 | .410 | -3.041 | .178 | -.025 | .780 |

| Constant | 3.426*** | .000 | 74.797*** | .000 | 5.030*** | .000 |

| Adjusted R-squared | .082 | .071 | .083 | |||

| Number of observations | 1,189 | 1,189 | 1,189 | |||

| Note: Sample includes savings and thrift plans with flat match structures. Significance is denoted by Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | ||||||

The coefficients on the other variables generally align with our expectations. Compared with plans in wholesale trade, plans in the financial services, insurance, and real estate industries have statistically higher maximum match rates—a result driven entirely by the match rates. For example, the average maximum match rate and the average match rate for these industries are higher—1.1 percentage points and 15.2 percentage points higher, respectively—than the corresponding rates in wholesale trade. In addition, establishment size is positively correlated with employer match rates. Plans among establishments with at least 500 employees have an average maximum match rate that is 0.2 percentage point higher and an average match rate that is 4.9 percentage points higher than corresponding plan rates in smaller establishments. However, match ceilings do not statistically differ across establishments of different size. Also, establishments located in metropolitan areas have statistically higher maximum match rates than do firms in nonmetropolitan areas, while establishments in the South have statistically lower maximum match rates than do firms in the Northeast. To capture the generosity of establishments, we also control for the share of workers with DB plans, the share of full-time workers, and the share of union workers. There is no statistically significant correlation between these variables and the maximum match rate.

Automatic enrollment and total compensation costs. In this section, we use a series of OLS regressions to examine the relationship between autoenrollment and total employee compensation. Because compensation costs in the NCS data are calculated at the job level and because workers at various jobs within an establishment often share the same plan, we estimate these equations at the establishment level. Establishment-level compensation costs are calculated as a weighted average of the job-level compensation costs within the establishment. The key variable of interest in our models is an indicator for the existence of at least one savings and thrift plan with automatic enrollment at that establishment. We control for industry, establishment size, share of workers in the plan who also have a DB plan, proportion of full-time and union workers, metropolitan area, and geographic region. We report robust standard errors, clustered on the state level.

Table 7 shows the results of our OLS regression of total employer costs on automatic enrollment. While automatic enrollment is positively correlated with total costs, standard significance tests suggest that its coefficient is not significantly different from zero. The results also show that firms in transportation and public utilities have total compensation costs per labor hour that are $16.50 higher than those of firms in wholesale trade. Compared with costs in wholesale trade, costs are also higher in agriculture, mining, and construction ($8.80 higher) and in financial services, insurance, and real estate ($7.80 higher). Other factors that are positively correlated with total compensation are establishment size, the share of full-time workers, being in a metropolitan area, and being in the Northeast. Establishments with more than 5,000 employees have total compensation costs per labor hour that are $12.60 higher than those in establishments with less than 500 employees. Establishments in the Midwest and South regions have total labor costs that are $14.40 and $12.50 lower, respectively, than the costs of firms located in the Northeast, while establishments in metropolitan areas have costs that are $6.61 higher, on average, than the costs of counterparts who are not in metropolitan areas.

It is possible that the lack of statistically significant correlation between autoenrollment and total costs is due to a canceling mechanism, in which a positive correlation with DC costs and a negative correlation with non-DC costs cancel each other. To explore this possibility, we jointly estimate a number of cost equations in a seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR) model. This estimation allows us to test cross-equation restrictions and the possibility that the error terms across equations are contemporaneously correlated.41

The second set of regressions in table 7 shows the SUR results for DC costs and non-DC costs. We find no evidence that DC costs are different between firms with and without autoenrollment. We also find no evidence that these firms have different non-DC costs, nor any evidence that DC costs crowd out non-DC costs. We cannot reject the hypothesis that the coefficient on automatic enrollment is jointly equal to zero in the two equations. That means that, once other factors are controlled for, neither DC costs nor non-DC costs are related to automatic enrollment.42 The results show that establishments in which all workers are covered by a DB plan have, on average, $4.10 higher non-DC compensation costs and $0.23 lower DC costs than do establishments with no DB-covered workers. On average, establishments with more employees have both higher DC costs and higher non-DC costs, and so do firms in metropolitan areas. Compared with the Northeast region, the Midwest, South, and West regions have DC costs per labor hour that are $0.56, $0.46, and $0.36 lower, respectively.

| Variable | Total costs | DC costs | Total non-DC costs | DC cost share (model 1) | DC cost share (model 2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | St. error | Coeff. | St. error | Coeff. | St. error | Coeff. | St. error | Coeff. | St. error | |

| Autoenrollment | 1.418 | 0.318 | 0.028 | 0.712 | 1.337 | 0.369 | 0.001 | 0.217 | 0.001 | 0.438 |

| Industry (omitted = wholesale trade) | ||||||||||

| Agriculture, mining, and construction | 8.831*** | .004 | .266 | .229 | 8.531** | .047 | .003 | .255 | -.001 | .805 |

| Manufacturing | 1.032 | .572 | -.022 | .898 | 1.159 | .730 | -.002 | .474 | -.002 | .340 |

| Transportation and public utilities | 16.506*** | .000 | .921*** | .000 | 15.559*** | .000 | .007** | .011 | .003 | .179 |

| Retail trade | -3.209 | .193 | .023 | .913 | -3.146 | .440 | .003 | .216 | .005** | .020 |

| Financial services, insurance, and real estate | 7.790** | .024 | .493*** | .004 | 7.391** | .025 | .009*** | .000 | .007*** | .004 |

| Other services | 3.343 | .142 | .281* | .090 | 3.110 | .334 | .004** | .024 | .003 | .114 |

| Establishment size (omitted = < 500) | ||||||||||

| 500–999 | .769 | .665 | .115 | .295 | .639 | .764 | .002 | .180 | .001 | .280 |

| 1,000–2,499 | 3.686* | .061 | .312** | .002 | 3.431* | .081 | .004** | .013 | .002 | .120 |

| 2,500–4,999 | 9.085** | .039 | .298** | .015 | 8.841*** | .000 | .003 | .105 | .001 | .506 |

| ≥ 5,000 | 12.587*** | .005 | .543*** | .000 | 12.124*** | .000 | .003 | .118 | .000 | .805 |

| Share of workers with DB plans | 3.755** | .018 | -.226*** | .009 | 4.082** | .015 | -.005*** | .000 | -.007*** | .000 |

| Share of workers with health benefits | -1.198 | .734 | .040 | .869 | -1.019 | .829 | .003 | .315 | .004 | .240 |

| Share of workers with leave | -.194 | .946 | -.266 | .370 | -.181 | .975 | -.011** | .020 | -.011** | .039 |

| Share of workers with insurance | 6.336*** | .003 | .372** | .038 | 6.084* | .081 | .007*** | .001 | .004* | .052 |

| Share of workers with other costs | 7.035*** | .000 | .257*** | .001 | 6.764*** | .000 | .002 | .255 | .000 | .926 |

| Has other DC plan | 2.381** | .020 | .330*** | .000 | 2.027 | .134 | .006*** | .000 | .005*** | .000 |

| Share of full-time workers | 15.192*** | .000 | .587*** | .007 | 14.349*** | .001 | .006* | .056 | .001 | .765 |

| Share of union workers | .770 | .756 | .091 | .525 | .607 | .827 | .000 | .911 | -.001 | .640 |

| Metropolitan area | 6.606*** | .000 | .450*** | .000 | 6.208*** | .005 | .006*** | .000 | .004*** | .001 |

| Region (omitted = Northeast) | ||||||||||

| Midwest | -14.408*** | .007 | -.556*** | .000 | -13.854*** | .000 | -.005*** | .004 | -.002 | .252 |

| South | -12.491** | .015 | -.458** | .000 | -12.101*** | .000 | -.003* | .050 | -.001 | .489 |

| West | -8.050 | .123 | -.362*** | .001 | -7.695*** | .000 | -.004*** | .005 | -.003** | .044 |

| Flag for imputed costs | .139 | .929 | -.092 | .101 | -1.274 | .386 | .001 | .200 | .001 | .103 |

| Total costs quintile (omitted = bottom) | ||||||||||

| Second | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .001 | .722 |

| Middle | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .006* | .069 |

| Fourth | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .012*** | .000 |

| Top | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .017*** | .000 |

| Constant | 10.660* | .078 | -.118 | .746 | 12.068* | .092 | .012** | .019 | .013** | .013 |

| R-squared | .277 | .227 | .272 | .173 | .238 | |||||

| Number of observations | 930 | 930 | 930 | 930 | 930 | |||||

| Note: Sample includes establishments with savings and thrift plans with flat match structures. Significance is denoted by *p < .10, Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | ||||||||||

We also find that the share of DC costs in total compensation is not statistically significantly different between firms with and without automatic enrollment. Interestingly, the higher a firm’s average total compensation, the higher that firm’s spending on DC plans. For example, the DC cost share for firms in the middle quintile of total compensation is 0.6 percentage point higher than that for firms in the bottom quintile; for firms in the top quintile, the share is 1.7 percentage points higher.

Table 8 shows the SUR results for various employer costs. We group these costs into the following categories: DC costs, wages, legal costs (Social Security, Medicare, state and federal unemployment insurance, and workers’ compensation), health insurance costs, DB costs, costs for leave (vacation, holidays, sick leave, and other leave), costs for insurance (life insurance and short-term and long-term disability insurance), and other costs (nonproduction bonuses, severance pay, and supplemental unemployment insurance). Again, there is no evidence that firms with and without autoenrollment have different DC costs or that DC costs crowd out other forms of employer compensation. However, autoenrollment is associated with higher hourly costs for health insurance ($0.31 higher) and leave benefits ($0.27 higher) and with lower costs for DB pensions ($0.17 lower). A significance test rejects the null hypothesis that the coefficients on automatic enrollment across equations are jointly equal to zero

| Variable | DC costs | Wages | Legal costs | Health insurance costs | DB costs | Leave costs | Insurance costs | Other costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoenrollment | 0.030 | 0.875 | 0.072 | 0.308*** | -0.171** | 0.266* | 0.013 | 0.173 |

| | ||||||||

| Agriculture, mining, and construction | .239 | 5.970** | .834*** | .304 | .182 | .233 | .017 | .040 |

| Manufacturing | -.023 | .207 | .185 | .549** | .021 | .291 | .025 | .138 |

| Transportation and public utilities | .888*** | 9.751*** | 1.158*** | 1.531*** | 1.137*** | 1.804*** | .133*** | .156 |

| Retail trade | -.035 | -2.439 | -.351* | -.359 | -.290 | -.387 | -.039 | -.093 |

| Financial services, insurance, and real estate | .516*** | 3.675* | .088 | .736*** | -.049 | .950*** | .080** | 2.455 |

| Other services | .264 | 2.465 | .097 | .490** | -.128 | .589* | .002 | -.771 |

| Establishment size (omitted = < 500) | ||||||||

| 500–999 | .147 | .439 | .047 | .320** | -.153 | .313 | .043 | .035 |

| 1,000–2,499 | .339*** | 2.465** | .198** | .447*** | -.113 | .649*** | .087*** | .067 |

| 2,500–4,999 | .369*** | 5.196*** | .394*** | .287* | .084 | 1.247*** | .074*** | 3.234*** |

| ≥ 5,000 | .577*** | 7.341*** | .565*** | .541*** | .185 | 1.425*** | .058** | 3.235** |

| Share of workers with DB plan | 1.570 | .174* | .267 | 2.296*** | .591*** | .047** | .375 | |

| Has other DC plan | .384*** | 1.966** | .206*** | .401*** | .081 | .305** | .051*** | -.133 |

| Share of full-time workers | .829*** | 13.286*** | .992*** | 1.558* | .037 | 2.061*** | .139*** | .668 |

| Share of union workers | .076 | -1.377 | .310** | 2.043** | -.025 | .010 | .100*** | -1.279 |

| Metropolitan area | .486*** | 5.437*** | .455*** | .145*** | .024 | .780*** | .047** | -.002 |

| Region (omitted = Northeast) | ||||||||

| Midwest | ||||||||

| South | -.469*** | -6.984*** | -.703*** | -.658*** | -.179* | -1.269*** | -.099*** | -2.276** |

| West | -.350*** | -3.602*** | -.327*** | -.507*** | -.009 | -.599*** | -.060*** | -2.222** |

| Constant | -.099 | 8.887*** | 1.494 | 1.048*** | .116 | .132 | .022 | 1.368 |

| R-squared | .225 | .264 | .325 | .415 | .485 | .348 | .227 | .052 |

| Observations | 930 | 930 | 930 | 930 | 930 | 930 | 930 | 930 |

| Note: Sample includes establishments with savings and thrift plans with flat match structures. Significance is denoted by *p < .10, Source: Authors’ calculations using National Compensation Survey restricted-use microdata extract, | ||||||||

Interestingly, while the share of union workers in an establishment is positively correlated with legal costs, health insurance costs, and other insurance costs, it is not a statistically significant predictor of costs for DC plans, wages, DB pensions, or leave. Compared with establishments with no unionized workers, establishments in which all workers are unionized have, on average, $2.04 higher health insurance costs, $0.31 higher legal costs, and $0.10 higher insurance costs per labor hour. Overall, transportation industries and public utilities have the highest compensation costs.

Finally, the larger the share of workers covered by a DB plan, the lower the average DC costs, as these types of benefits are close substitutes. Establishments in which all workers are covered by a DB plan have, on average, DC costs per labor hour that are $0.32 lower and DB costs per labor hour that are $2.30 higher than corresponding costs in firms with no DB-covered workers. However, the share of workers with DB plans and the share of workers with more than one DC plan are positively correlated with a number of employee benefits. A possible explanation for this finding is that establishments with large shares of workers with DB plans or multiple DC plans pay higher total compensation, on average, to attract and retain more productive workers.43

Our models, in particular those looking at establishment costs, likely remind the reader of the empirical models typically found in the compensating differentials literature, which draws upon the theory of equalizing differences. According to Sherwin Rosen, that theory implies that otherwise identical employees who receive higher fringe benefits should be paid a lower wage.44 Previous tests of this theory with respect to pension benefits, however, often fail to find evidence for a compensating differential. The lack of accurate data on workers’ productivity frequently leads to omitted variable bias in empirical specifications and is considered to be the likely driver of the observed positive correlation between wages and pension benefits.

Since we are similarly unable to control for workers’ innate ability, unobserved worker productivity traits can cause an omitted variable bias in our estimation as well. However, we believe that the confounding effects of these traits are much smaller in our specification, for the following two reasons. First, our analysis focuses only on compensation packages that already include a pension plan. Thus, we include only individuals who have self-selected into pension jobs and are arguably more comparable to one another than to workers in nonpension jobs. Any additional bias resulting from self-selection on automatic enrollment is unlikely or expected to be small. Second, our analysis does not look for compensating differences between wage and nonwage benefits, but rather examines whether total compensation and its components depend on the structure of the pension plan (i.e., the presence of automatic enrollment); by itself, automatic enrollment does not provide a fringe benefit. Thus, we expect the correlation between autoenrollment and total compensation to be either zero or positive (if automatic enrollment increases productivity). Even if there is an unobservable workers’ self-selection of the type suggested by the compensating differentials literature, we would expect it to bias our results upward.45 Thus, the estimated coefficients on automatic enrollment in the regressions of compensation costs can be viewed as a conservative upper bound. On this basis, we conclude that there is no evidence of statistically significant differences in total compensation costs or DC plan costs between DC plans with and without automatic enrollment.

However, we did find statistically significant differences in the components of DC costs. Using nationally representative data, we confirmed the results of previous case studies, which have shown that automatic enrollment is associated with higher plan participation rates—7 percentage points higher, on average. We also found that plans with automatic enrollment offer maximum match rates that are 0.38 percentage point lower, on average, than are the rates of plans with autoenrollment. Given an average hourly wage of $26.20, an average participation rate of 68.7 percent, and an average maximum match of 3.2 percent in our sample, a simple calculation shows that the 0.38-percentage-point lower match rate translates into savings of about 7 cents per labor hour. These savings completely offset the additional costs of 6.5 cents resulting from higher participation rates. Since we find no statistically significant correlation between wages and automatic enrollment (see table 8), this result is consistent with our earlier finding of no statistical difference in DC plan costs with respect to autoenrollment. Instead, the cross-sectional evidence from the NCS suggests that in order to adapt to higher per-worker costs from autoenrollment, firms might be making adjustments only within the DC portion of their compensation packages.

Our descriptive analysis also showed that default contribution rates in autoenrollment plans are set at levels that do not take full advantage of the employer match. The roughly offsetting effects of higher participation rates and lower match rates suggest that, in our sample of plans, the defaults have only a weak contribution to the total difference in costs. However, to quantify this contribution correctly, we need information on the actual employee contributions and how they differ from the defaults. This is an interesting avenue for future research.

Most pension-related research has focused on employee behavior—whether workers participate in a

Using data on cross-sectional variation in plan features and costs—data derived from the restricted-access employer-level NCS—this article empirically examined the relationship between (1) automatic enrollment and (2) firms’ DC plan match structure, DC plan costs, and total compensation. We found that employer match rates are negatively and significantly correlated with autoenrollment. The maximum match rate averages 3.5 percent for plans without automatic enrollment and only 3.2 percent for plans with automatic enrollment. Even after controlling for other factors, we found that automatic enrollment is associated with a maximum match rate that is 0.38 percentage point (11 percent) lower. Among workers with autoenrollment plans, the default contribution rate averages only 2.8 percent (3.4 percent, with full autoescalation). Yet, to receive the maximum match, these workers would need to contribute an average of 5.1 percent of pay. In other words, employers with autoenrollment plans are setting the default contribution rate well below the rate needed for the maximum match. This allows them to contribute to more worker accounts without necessarily increasing their costs. That employers adopt such cost-minimizing strategies is further supported by our finding that total costs do not differ between firms with and without automatic enrollment, even though automatic enrollment is associated with a 7-percentage-point-higher plan participation rate. Furthermore, we found no evidence that DC costs crowd out other forms of employer compensation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The authors thank the Social Security Administration (SSA) for its generous financial support, which was provided through the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College as part of the Retirement Research Consortium (RRC). The research reported herein was conducted with restricted access to BLS data. The findings and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views of SSA, BLS, the Congressional Budget Office, any agency of the federal government, the RRC, the Urban Institute, its board, or its funders. The authors would like to thank Keenan Dworak–Fisher for valuable comments and for his instrumental help in gaining access to and using the data source. The authors are also grateful to Richard Johnson, Enareta Kurtbegu, James Poterba, Jack VanDerhei, and participants at research seminars at the Urban Institute, BLS, the Netspar International Pension Workshop, the APPAM Fall Research Conference, and the 2015 Annual American Economic Association Meeting, for helpful suggestions. All mistakes are our own.

?pagebreak>?pagebreak>?pagebreak>?pagebreak>?pagebreak>?pagebreak>?pagebreak>?pagebreak>?pagebreak>?pagebreak>?pagebreak>?pagebreak>?pagebreak>Barbara A. Butrica, and Nadia S. Karamcheva, "Automatic enrollment, employer match rates, and employee compensation in 401(k) plans," Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2015, https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2015.15

1 The Survey of Income and Program Participation shows that 59 percent of eligible workers in the bottom income tercile participate in a DC plan, compared with 85 percent of those in the top tercile who do. See Nadia Karamcheva and Geoffrey Sanzenbacher, “Bridging the gap in pension participation: how much can universal tax-deferred pension coverage hope to achieve?” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 13, no. 4, 2014, pp. 439–459.

2 It has been reported that only 3 out of 10 plan sponsors say “all or nearly all” of their participants defer enough income to take full advantage of the maximum employer match. See Nevin Adams, “PLANSPONSOR’s 2011 DC Survey: points of hue,” PLANSPONSOR Magazine, November 2011.

3 Gary V. Engelhardt, “State wage-payment laws, the Pension Protection Act of 2006, and 401(k) saving behavior,” Economics Letters 113, 2011, pp. 237–240.

4 John Beshears, James Choi, David Laibson, and Brigitte C. Madrian, “The impact of employer matching on savings plan participation under automatic enrollment,” in David A. Wise, ed., Research findings in the economics of aging (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2010), pp. 311–327; James Choi, David Laibson, and Brigitte C. Madrian, “Plan design and 401(k) savings outcomes,” National Tax Journal 57, 2004, pp. 275–298; James Choi, David Laibson, Brigitte C. Madrian, and Andrew Metrick, “For better or for worse: default effects and 401(k) savings behavior,” in David A. Wise, ed., Perspectives on the economics of aging (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2004), pp. 81–121; James Choi, David Laibson, Brigitte C. Madrian, and Andrew Metrick, “Defined contribution pensions: plan rules, participant decisions, and the path of least resistance,” in James M. Poterba, ed., Tax Policy and the Economy, volume 16 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), pp. 67–114; and Brigitte C. Madrian and Dennis F. Shea, “The power of suggestion: inertia in 401(k) participation and savings behavior,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 116, no. 4, pp. 1149–1187.

5 See Choi et al., “Defined contribution pensions.”

6 Alan L. Gustman and Thomas L. Steinmeier, “What people don’t know about their pensions and Social Security,” in William G. Gale, John B. Shoven, and Mark J. Warshawsky, eds., Private pensions and public policies (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2004), pp. 525–549.

7 See National Compensation Survey: employee benefits in the United States, March 2014, bulletin 2779 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014), https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2014/ebbl0055.pdf. Even among full-time workers—whose participation rates are typically higher—participation rates were 89 percent in DB pensions and only 71 percent in DC plans; see chapter 8, “National compensation measures,” BLS handbook of methods (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2012), https://www.bls.gov/opub/hom/pdf/homch8.pdf.

8 See Choi et al., “Plan design”; and Choi et al., “For better or for worse.”

9 For a brief exposition of the cross-subsidizing incentives from nondiscrimination testing, see Peter J. Brady, “Pension nondiscrimination rules and the incentive to cross subsidize employees,” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 6, no. 2, 2007, pp. 127–145.

10 See Stacy Sandler, Scott Cole, and Robin Green, “Annual 401(k) survey: retirement readiness” (New York, NY: Deloitte Development LLC, 2011). Of the sponsors who implemented automatic enrollment, 43 percent found a positive impact of automatic enrollment on their nondiscrimination test results and only 1 percent found a negative effect.

11 Beshears et al., “The impact of employer matching”; Choi et al., “Plan design”; Choi et al., “For better or for worse”; Choi et al., “Defined contribution pensions”; and Madrian and Shea, “The power of suggestion.”

12 Madrian and Shea, “The power of suggestion.”

13 A survey of large U.S. firms found that 59 percent of employers in 2010 had adopted automatic enrollment for new employees, up from 24 percent in 2006 (before the passage of the PPA); another 27 percent of firms without automatic enrollment reported that they were likely to adopt it within a year. See Amy Atchison, “Survey findings: hot topics in retirement 2010” (Lincolnshire, IL: Hewitt Associates LLC, 2010). In its annual survey of member companies, the Plan Sponsor Council of America (PSCA) also reported that 46 percent of plans had an automatic enrollment feature in 2011, up from 24 percent in 2006 and 4 percent in 1999. See “PSCA’s 55th Annual Survey of profit sharing and 401(k) plans” (Plan Sponsor Council of America, 2012); and Mauricio Soto and Barbara Butrica, “Will automatic enrollment reduce employer contributions to 401(k) plans?” (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2009).

14 Specifically, the PPA removed disincentives to adopting automatic enrollment by (1) offering more attractive safe harbor rules, (2) preempting state payroll-withholding laws, and (3) protecting employers from fiduciary responsibility for their 401(k) plans’ investment performance. See Martha P. Patterson, Tom Veal, and David L. Wray, “The Pension Protection Act of 2006: essential insights” (Washington, DC: Thompson Publishing Group, 2006); and Patrick Purcell, Automatic enrollment in section 401(k) plans, CRS report for Congress RS21954 (Washington DC: Congressional Research Service, 2007). According to Bernard O’Hare and David Amendola (“Pension Protection Act: automatic enrollment plans,” New York Law Journal 237, no. 104, 2007), before the passage of the PPA, many employers were hesitant to adopt automatic enrollment because of state payroll-withholding laws that might have subjected them to lawsuits by plan participants. Indeed, Engelhardt (“State wage-payment laws”) found that, after the passage of the PPA, 401(k) participation increased more in states that required their employers to obtain an employee’s written permission before deducting any contributions from employee wages.

15 M. Andersen, S. Atlee, D. Cardamone, B. Danaher, and S. Utkus, “Automatic enrollment: benefits and costs of adoption” (Valley Forge, PA: The Vanguard Center for Retirement Research, 2001).

16 Pamela Hess and Yan Xu, “2011 trends and experiences in defined contribution plans: paving the road to retirement” (Aon Hewitt, 2011).

17 See “PSCA’s 54th Annual Survey of profit sharing and 401(k) plans” (Plan Sponsor Council of America, 2011).

18 Andersen et al., “Automatic enrollment.”

19 Soto and Butrica, “Will automatic enrollment reduce employer contributions to 401(k) plans?”

20 Jack VanDerhei, “The impact of automatic enrollment in 401(k) plans on future retirement accumulations: a simulation study based on plan design modifications of large plan sponsors,” issue brief 341 (Washington, DC: Employee Benefit Research Institute, 2010).

21 A PSCA survey reported that the most common default deferral is 3 percent of pay; see “PSCA’s 55th Annual Survey of profit sharing and 401(k) plans” (Plan Sponsor Council of America, 2012). Purcell (“Automatic enrollment”) notes that many plan sponsors have been reluctant to set the default contribution rate higher than 3 percent of pay, because that was the rate used in examples of permissible automatic enrollment practices published by the Internal Revenue Service.

22 Madrian and Shea, “The power of suggestion.”

23 William E. Nessmith, Stephen P. Utkus, and Jean A. Young, “Measuring the effectiveness of automatic enrollment” (Valley Forge, PA: The Vanguard Center for Retirement Research, 2007).

24 The NCS excludes several types of workers from its survey scope: workers who set their own pay (such as owners, officers, or board members of incorporated firms), workers in positions with token pay, and student workers in set-aside positions. The NCS removes these workers from its total employment count on the basis of the frequency of such workers in sampled establishments, as identified during sample initiation.

25 See chapter 8, “National compensation measures,” BLS handbook of methods (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2012), https://www.bls.gov/opub/hom/pdf/homch8.pdf.

26 For more information, see section 10.5 in Martin Holmer, Asa Janney, and Bob Cohen, “PENSIM overview” (Policy Simulation Group, September 2012).

27 Automatic enrollment is much less prevalent in our data than in data reported in industry studies. Among workers in all savings and thrift plans in our data—including workers with tiered match structures—19 percent have plans with an autoenrollment provision. At the establishment level, 25 percent of establishments with savings and thrift plans have at least one plan with automatic enrollment. In contrast, the PSCA's 54th Annual Survey referenced above reports that 41.8 percent of plans had automatic enrollment in 2010. We believe the difference in data may be due to differences in samples. Our sample includes only savings and thrift plans and is nationally representative. In contrast, most industry studies are based on large plans and are not nationally representative.

28 While only 12 percent of workers in our sample have wages in the bottom tercile of the wage distribution, 54 percent have wages in the top tercile. Because the terciles are based on the overall distribution of wages and include establishments with and without DC plans, this result reflects that workers with higher wages are more likely to have access to DC plans.

29 See John Beshears, James Choi, David Laibson, and Brigitte C. Madrian, “The importance of default options for retirement savings outcomes: evidence from the United States,” in David A. Wise, ed., Social Security policy in a changing environment (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2009), pp. 167–195; Choi et al., “Plan design”; Choi et al., “For better or for worse”; Choi et al., “Defined contribution pensions”; and Madrian and Shea, “The power of suggestion.”

30 See Choi et al., “Plan design”; and Choi et al., “For better or for worse.”