An official website of the United States government

United States Department of Labor

United States Department of Labor

Crossref 0

Perspectivas históricas de la Revista Internacional del Trabajo 1921‐2021: un siglo de investigación sobre el mundo del trabajo1, Revista Internacional del Trabajo, 2022.

Un siècle de recherche sur le monde du travail: un regard historique sur la Revue internationale du Travail, 1921‐20211, Revue internationale du Travail, 2022.

Historical perspectives on the International Labour Review 1921–2021: A century of research on the world of work1, International Labour Review, 2022.

To help mark the Monthly Labor Review’s centennial, the editors invited several producers and users of BLS data to take a look back at the last 100 years. This second article in a series of four recounts the “middle years” (1930–80) of the federal government’s premier publication on labor economics and flagship journal of the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The five decades from 1930 to 1980 saw the Review blossom in its three roles of recorder, analyzer, and mover of important economic events.1 This second of four installments delves into what went on in those years and how the Review fulfilled those roles in capturing the tenor of the times.

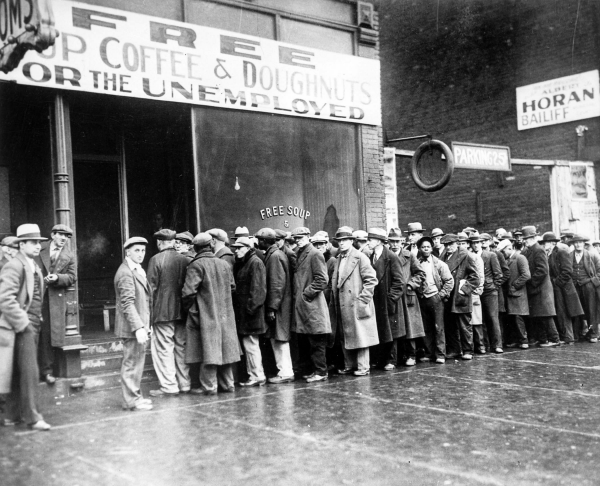

The Great Depression brought with it suffering on a scale not seen in the United States since perhaps the Civil War, and the Review covered it all. A survey conducted by the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce in May 1932 estimated that 35.8 percent of all families residing in Philadelphia were in some kind of economic distress, from having insufficient food, clothing, or heat, to having been evicted for unpaid rent, to lacking medical attention, to suffering the loss of their home or furniture.2 More than coincidentally, the Review of the early 1930s had a number of features on unemployment, employment, welfare (then called relief), and social insurance that augmented and amplified the survey’s findings. Articles and other features by Frederick E. Croxton (sometimes with a coauthor) illustrate the dire mood of the times: “Displacement of Morse telegraphers in railroad systems” (May 1932); “Family unemployment in Syracuse, N.Y.” (November 1931) and “Emergency labor camps in Pennsylvania” (June 1932), both with John Nye Webb; “An analysis of the Buffalo, N.Y., unemployment surveys, 1929 to 1932” (February 1933), synthesizing findings from four surveys on unemployment in a city hard hit by the depression; and “Longshore labor conditions and port decasualization in the United States” (December 1933, with Fred C. Croxton), a commentary on the need to eliminate the employment of casual longshore workers in order to stabilize the workforce in an industry whose workers’ average earnings fell drastically from 1927 to 1932. Also illustrative of both the profound impact of the recession and the need for policy-guided social help are “Employment, hours, earnings, and production under the N.R.A.” (Witt Bowden, May 1934), an examination of the role of the National Industrial Recovery Act in checking and then reversing the falling earnings of U.S. workers in the face of increasing productivity; the two-part “Operation of unemployment-benefit plans in the United States up to 1934” (Anice L. Whitney, June and July 1934), a review of three BLS studies of unemployment benefit systems in the United States at a time when the only public unemployment insurance compensation system was at the state level and had just been established in Wisconsin; and “Unemployment relief from federal funds, first 11 months of 1934” (Florence M. Clark, March 1935), a piece laying bare the extent of the numerous purposes for which federal funds were being granted to alleviate the human suffering and economic damage caused by the depression. In her article, Clark pointed out that, in April 1934, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration established an entire rural rehabilitation program aimed specifically at providing different forms of relief for four kinds of rural families affected by the depression. The relief measures were (1) seed and farm animals, equipment, and buildings for families residing on fertile land; (2) relocation to fertile land or employment on land-related work projects for families residing on submarginal land; (3) commodity exchanges at which “labor may be performed in exchange for surplus commodities produced by farm families on relief,” for families in towns with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants; and (4) all of the preceding measures for “families left ‘stranded’ by the relocation or abandonment of local industries.”

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, begun in 1933, resulted in the Social Security Act of 1935, a landmark piece of legislation that led to a spate of articles published in the Review. As Phyllis Groom put it, the “cost of living, expenditures, and consumption were analyzed in terms of the depression, and a series of articles…described the plight of agricultural migrants.”3 Leading the effort was BLS economist Faith M. Williams, who, either alone or together with colleagues, produced no fewer than 25 articles on the first three of these topics in a span of about 6½ years. From 1934 through 1939, Williams and her colleagues published articles on the cost of living of federal employees residing in Washington, DC (March 1934, July 1934); the cost of goods purchased by wage earners and lower-salaried workers (September 1935); living costs in 1938 (March 1939); expenditures of wage earners and lower-salaried workers (April 1935) and of wage earners and clerical workers in 11 New Hampshire communities (March 1936), in Richmond, Birmingham, and New Orleans (May 1936), in the four Michigan cities of Detroit, Grand Rapids, Lansing, and Marquette (June 1936), in Boston and Springfield, Massachusetts (September 1936), and in Rochester, Columbus, and Seattle (December 1936); expenditures of wage earners and lower-salaried clerical workers in New York City (January 1937) and of families of Black wage earners and clerical workers in Richmond, Birmingham, and New Orleans (April 1937); changes in family expenditures in the post–World War I period (November 1938); and food consumption at different economic levels (April 1936). Then, beginning in December 1939 and every month thereafter through August 1940, the effort culminated in a running series of nine articles by Williams and Alice C. Hanson on various aspects of family and individual expenditures: first, two general articles on, respectively, the expenditure habits of wage earners and clerical workers (December 1939) and income, family size, and the economic level of the family (January 1940) and, then, articles specifically on wage earners’ and clerical workers’ expenditures for clothing (February); transportation and recreation (March); housing (April); medical care, personal care, and miscellaneous items (May); and housefurnishings and household operation (June). The eighth entry in the series was a general article on the savings of wage earners and clerical workers (July), and the series concluded in August with an article specifically on wage earners’ and clerical workers’ expenditures on food. Rounding out Williams and colleagues’ articles on wage earners’ and clerical workers’ expenditures were two solo articles, one in June 1937 by Hanson reporting on workers in the five Pennsylvania cities of Johnstown, Lancaster, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Scranton, and the other in September 1937 by Genevieve B. Wimsatt canvassing workers in the five California cities of Los Angeles, Modesto, Sacramento, San Diego, and San Francisco–Oakland.

As mentioned, articles on agricultural migrants also followed the introduction of the New Deal and Social Security. Paul S. Taylor and Tom Vasey began the discussion with their February 1936 piece, “Drought refugee and labor migration to California, June–December 1935,” highlighting the efforts of state inspectors to demographically classify the large numbers of unskilled workers seeking agricultural employment in California. Migrating mostly from the drought and “Dust Bowl” that devastated the nation’s Great Plains states, these workers, often with their families in tow, sought out California for work because of the prospects that that state’s continuous harvests would keep them employed for the foreseeable future. The movement, said Taylor and Vasey, “represents a labor migration and population shift…of major import….an index of major problems of relief, rehabilitation, and human resettlement with which…the Government [is] grappling and must continue to grapple.” Explicitly following up on Taylor and Vasey’s article was one by Edward J. Rowell, titled “Drought refugee and labor migration to California in 1936,” published in December of that year. In it, besides noting that the flow of migrants to the state continued throughout the year, Rowell emphasized that neither government agencies nor private establishments seemed to be able to cope with the problems in settlement, relief, housing, health, and living standards that accompanied the migrants on their path to what might best be described as “unsettled employment conditions.” Taylor and Rowell continued, both separately and as coauthors, to underscore California’s role as a destination for migrant agricultural workers in three more articles published during the 1930s: in the first, “Migratory farm labor in the United States” (Taylor, March 1937), the state was featured as part of a broader discussion about the issue of the nation’s agricultural migrants; in the second, titled “Refugee labor migration to California, 1937” (August 1938), coauthors Taylor and Rowell noted that many of the migrants had lost their farms when the price of cotton fell not long after World War I. Subsequently, these former farm owners became tenants or sharecroppers, then laborers, and, finally, migrants when cotton prices fell again, followed by drought and mechanization. In the third article, titled “Patterns of agricultural labor migration within California” (November 1938), Taylor and Rowell collaborated again, this time to point out the challenges faced by the state of California in having to educate the migrants’ children, the vast majority of whom spoke a language other than English.

Finally, a series of three articles published successively in 1937 noted that California wasn’t the only destination of migrant agricultural workers over the decade. In July, N. A. Tolles reported on a Department of Labor “Survey of labor migration between states” which found, among other things, that, besides California, “the cotton and vegetable areas of the Southwest, the apple, hop, and berry regions of the Pacific Northwest, the pea fields of Idaho, the beet fields of Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho, the berry fields of Arkansas, and the citrus and vegetable areas of Florida” were all attractive havens for migratory workers from outside the state (in addition to attracting many in-state agricultural migrants). Despite the findings of the survey, Tolles concluded that “very little is known concerning the regularity of employment or the comparative earnings” of those migratory workers “who seek permanent relocation.” Following on the heels of Tolles’ article, Paul H. Landis wrote about “Seasonal agricultural labor in the Yakima Valley” in the August issue of the Review. Landis estimated that anywhere from about 30,000 to 37,000 “transient” workers found agricultural work in the valley from June to October each year, harvesting cherries, hops, and Washington’s famous apples. The trouble was that few of these workers were employed full time and, during the rest of the year, they were likely unemployed or, if they were lucky, found employment in nonagricultural jobs. On a more general note, Julius T. Wendzel’s September article, “Distribution of hired farm laborers in the United States,” drew a distinction between farms with just one or a few hired hands and those which hired workers in large numbers. Citing an earlier study by Louise E. Howard which found that, on farms with only one or a few hired agricultural workers, these workers enjoyed a close relationship with their employer that assured them relatively good working conditions,4 Wendzel pointed to that very relationship as, ironically, a likely reason for the federal government’s reluctance to enact legislation extending worker’s rights to agricultural labor. Viewing these hired hands as not unlike family members, who often received little or even no pay for their work and to whom it was felt that, therefore, no legislation need be extended, the government, according to Wendzel, neglected the fact that, though small in percentage, the number of farms with more than a few workers was considerable and the number of workers on them was even greater. In all, Wendzel found that almost 650,000 out of about 1,650,000—or approximately 40 percent of all—hired agricultural laborers worked on farms which were large enough that the employee–employer relationship was unlikely to be the familial one described. It was these workers who needed worker’s rights legislation, he maintained.

The coming of World War II brought a number of new issues to the Review. At first, with the war confined to Europe, a new feature on foreign wartime emergency controls was introduced and attention was paid to how the war was affecting labor in European countries. Later, after Pearl Harbor, the focus shifted to how the nation’s war industries were coping with increases in the supply of labor and in productivity required to meet wartime demands. In this regard, the titles alone of several articles are illustrative: “Effect of defense program on private manufacturing employment” (Thomas F. Corcoran and Harrison F. Houghton, January 1942); “Labor in transition to a war economy” (Witt Bowden, April 1942); “Working hours in war production plants, February 1942” (Harrison F. Houghton, May 1942); “War and the increase in federal employment” (Kathryn R. Murphy and Simon Krixtein, August 1942); “Effect of the war on textile employment” (Ruth E. Clem, September 1942); and “Problem of absenteeism in relation to war production” (Duane Evans, January 1943). A series of articles running over several issues examined the war’s effect on labor in a number of different countries and regions of the world: Australia (March 1942), New Zealand (April 1942), French North Africa (May 1943), Hungary (June 1943), Greece (August 1943), India (September 1943), Bulgaria (October 1943), Yugoslavia and Fascist Italy (November 1943), the Netherlands (January 1944), Belgium (February 1944), Thailand (June 1944), China (January 1945), and, finally, the defeated Axis power Germany itself (March 1945). By 1945, however, with the ending of the war in both Europe and the Pacific theater, the Review turned to what the economic picture would look like after the war.

One issue that occupied the Review’s ruminations about the postwar scenario was how the nation’s economy would absorb the millions of returning servicemen and women. The September 1945 article “Income from wages and salaries in the postwar period,” by Robert J. Myers and N. Arnold Tolles, expressed the concern that the only way the postwar economy could sustain the wartime level of wage and salary income would be under the combination of full employment and considerably higher wage rates. The dilemma the authors posed for the economy was that

With anything less than full employment, the volume of wage [and] salary payments would decline; a level of employment comparable to that of the prewar year 1939 might result in a drop of roughly $40 billion, or about 40 percent [presumably, of gross domestic or gross national product]….The achievement of full employment, however, will require a level of production far beyond any level previously attained in peacetime.

Thus, it seemed impossible—or at least highly improbable—that wages and salaries could remain at wartime levels. Of course, events disproved this pessimistic view: the newly burgeoning consumer economy, and the merchants who strove to keep up with it, not only kept wages from falling, but actually fueled a remarkable wage growth—and all under the aegis of as close to a full economy as could be achieved.

With unemployment quite low from just after the war on into the mid-1950s,5 the incidence of collective bargaining rose in those years. Union membership was at its highest then, having reached a peak of 28.3 percent of employed workers in 1954,6 and the Review published a multitude of pieces germane to the situation. Covering a substantial portion of the period of high union influence was a running feature titled “Developments in industrial relations” that began in May 1951. The feature reported on the provisions of contracts negotiated between unions and companies and between unions and government agencies. A conduit of valuable information for both company executives and union leaders (as well as labor economists) during a time of union expansion, the feature continued past that time and well into the 1990s, in its last year or so under the simpler title “Industrial relations.”

Throughout the postwar years, numerous articles related the story of the burgeoning influence of unions and the agreements achieved through collective bargaining. The topics ranged from the highly general to the narrowly circumscribed and from the ostensibly prescriptive7 to the purely descriptive. In the vein of the broad, general theme was a special section titled “50 years’ progress of American labor” in the 35th-anniversary issue of the Review in July 1950. The section, in honor of the centennial of labor leader Samuel J. Gompers, founder of the American Federation of Labor, presented nine articles on various aspects of working life related to the American laborer. From the worker’s relation to industry as a whole and to his or her particular job, to the worker’s quest for job security, to the role of government and labor legislation in the worker’s life, the articles, written by notables ranging from a former BLS commissioner, to the chairman of the Social Security Board, to labor leaders, to university professors, as well as BLS economists, examined the progress made, and the obstacles encountered, by U.S. workers from all over the labor spectrum. At the other end of the continuum were more narrowly circumscribed yearly reports on union wage scales in a number of occupations in four industries (building trades, local city truckdriving, local transit, and printing) from 1947 to 1956 and one industry (baking) from 1947 to 1952. In all these occupations and industries, wages showed an uninterrupted, often substantial, rise from year to year over the entire period.

In the realm of prescriptive topics was a February 1951 piece titled “Perlman’s theory of the labor movement” in which five labor economists revisited their colleague Selig Perlman’s idea that the American labor movement, unlike the European labor movement, was job conscious rather than class conscious. Marxists had argued that American unions were too concerned with improvements in wages and working conditions (thereby implying an acceptance of capitalism) and not concerned enough about class distinctions and inciting revolution. Perlman countered their argument by pointing out that the American situation was different from the European one: workers were, on the whole, economically better off in the United States, and whatever conflict there was between employers and employees was due not to capitalism per se, but to the downward pressure on wages—correctable by unions—exerted by the marketplace. Thus, the goals of unions were more businesslike than those of their European counterparts and were properly defined by union members rather than intellectuals such as Marx and Lenin. Through the Review, Perlman’s theory, originally set forth in 1928, was assessed against the empirical realities that had accrued since its inception. There was no consensus among the five economists: three found that Perlman’s theory was still valid in 1951, and two maintained that changing events had left the theory wanting in its original form.

As regards descriptive pieces, because describing what takes place in the labor market is the chief role—indeed the sine qua non—of the Review, the vast majority of its articles fall into this category. During the postwar years, numerous aspects of collective bargaining were discussed. The list is long: grievance procedures, health plans, wage scales, reemployment of veterans, guaranteed employment, employment of workers with disabilities, premium pay for weekend work, employer and employee obligations and rights, arbitration provisions, no-raid agreements, sickness and accident benefits, union-security provisions, safety provisions, cost-of-living wage adjustments, employee-benefit plans, wage escalator clauses, length-of-service benefits, work stoppage provisions, the employer’s duty to supply data for collective bargaining, shift operations and pay differentials, pension plans (a series of three articles published, respectively, in March, May, and July 1953), holiday provisions, strike-control provisions, paid rest-period provisions, military-service payments, anti-Communist provisions, reporting and callback pay, paid leave on death in family, paid jury leave, seniority, employment and age, and dismissal pay provisions. BLS analysts reported on all these topics, bringing the increasing role of unions and collective bargaining during the immediate postwar years to the forefront of the public’s attention.

Union membership began to wane in 1955 and has declined consistently since then.8 Still, the lot of many workers improved, and the focus of the Review shifted to what economist Edward D. Hollander described in the June 1963 issue as the national agenda of the 1960s: “solving the stubborn problems of the less favored and all-too-large minorities, who have been relegated to the periphery or who are altogether outside the labor force.” As the Civil Rights Movement brought Americans face to face with the legacy of slavery, as the War on Poverty sought to better the conditions of minorities and the poor, and as the Great Society endeavored to balance the exigencies of military combat with the needs of the War on Poverty, the Review aimed its sights on all these topics and put forth a number of articles addressing them. The contrast between the period before the inception of these momentous movements and programs and the years that followed is perhaps best brought out in the difference between the rosy picture painted by three articles that described the former time and the reality check afforded by numerous articles published after that time. A December 1962 article by Marion Hayes spoke of “A century of change: Negroes [sic] in the U.S. economy, 1860–1960,” a century in which, to be sure, African Americans were better off at the end than they were at the beginning, but only because at the beginning they were under the utterly shameful, crushing yoke of slavery. The economic, health, and educational gains cited by Hayes, while real, still left African Americans considerably behind Whites in many measures of well-being. In June 1963, two articles under the feature “Measures of workers’ wealth and welfare” touted a large increase in “Workers’ wealth and family living standards” (Helen H. Lamale) and government programs aimed at boosting “Social expenditures and worker welfare” (Ida C. Merriam) as instrumental in raising living standards during the 1950s. However, the first article neglected to talk about the wealth and living standards of African Americans, and the second failed to discuss how, if at all, the social welfare programs benefited those same African Americans.

By 1964, however, with the advent of the Civil Rights Movement, the War on Poverty, and the Great Society, the overall situation of African Americans had begun to change for the better. Reflecting the change, the Review began to publish article after article on various aspects of these great undertakings—a phenomenon that lasted well into the 1970s. Each year brought a spate of new articles, many of whose titles attested to the remarkable turnaround. A sampling of articles, one or more from each of those years, is illustrative:

The 1960s. Among the first Review articles relating the historic events taking place in the sixties was March 1964’s “Poverty in America,” an excerpt from chapter 2 of the annual report of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers. The article brought home the point that the endemic poverty which was an everyday experience of 9.3 million families in the United States could not even be addressed, let alone solved, until the majority of Americans recognized its existence. The poor, said the Council, lived in “a world apart,…isolated from the mainstream of American life and…concerned with [their] day-to-day survival.” Focusing on the long term, the Council laid out a 12-point strategy against the root causes of poverty. Then, in May and June 1965, the Review published Dorothy Newman’s two-part treatise on “The Negro’s [sic] journey to the city.” In the first part, the author recounted African Americans’ migration from the rural South to large metropolitan areas across the country in the hope of finding better jobs and more education. Newman described the migration as “unparalleled in American history.” In the second part, she contrasted the relative paucity of jobs available to African Americans at the time with the availability of jobs for immigrants at the turn of the 20th century. She concluded that “industry appear[ed] to have played a hoax” on African Americans, enticing them to leave the farm for cities in which manufacturing employment was declining. Subsequently, shedding further light on the plight of urban Blacks, James R. Wetzel and Susan S. Holland compared the employment situation of Whites and Blacks living in “Poverty areas of our major cities” in the October 1966 issue of the Review. Their overall finding was that, by almost every measure of economic well-being, including unemployment rate, hours worked, labor force participation rate, and type of employment (skilled vs. unskilled jobs), African Americans living in poverty areas were less well off than Whites living in those same areas.

The year 1967 saw the Review publish four articles on race and discrimination excerpted from the winter meetings of the Industrial Relations Research Association (IRRA), a labor organization for professionals in industrial relations and human resources. In the first, titled “Poverty in the ghetto—the view from Watts,” published in the February issue, Paul Bullock focused on the cynicism he found in residents of Watts, the Los Angeles community that had suffered riots 2 years earlier. Bullock cited the duplicity of the larger U.S. society in, at the same time, condemning those residents (and others living in similar circumstances) when they were unable to live up to the behavior and morality of the larger society, yet imposing conditions, such as poor public education and mass incarceration, that made it difficult for them to do so. The second and third articles on race and discrimination appeared in the March issue. In “Processing employment discrimination cases,” Alfred W. Blumrosen examined the shortcomings of the otherwise vaunted Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Citing the view of supporters of civil rights legislation that the act, as passed by Congress, was a “watered-down” version of the original conception and a “toothless tiger,” Blumrosen pointed to its detrimental effect on the individual right to sue. Standing with the civil rights supporters and the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission, he called for further legislation to restore the powers that had been originally proposed for the act before the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives stripped it of those powers. In the other March article on discrimination, Peter B. Doeringer called to account “Discriminatory promotion systems” that subtly limited African Americans’ opportunities for advancement on the job. Never explicit, the patterns of racial discrimination inhering in these promotion systems, maintained Doeringer, could be divided into three broad categories: (1) those restricting Black workers to the lower paying job classifications and ladders for promotion within a given department, (2) those restricting Black workers to entire departments that were less desirable or to unskilled job classifications that had no possibility of promotion, and (3) those with two separate lines of promotion, one (with more opportunities) for Whites and the other (with fewer opportunities) for Blacks. Doeringer proposed various remedies for dealing with these systems, but issued a number of caveats that could affect their adoption or efficacy. Finally, in the fourth article from the IRRA, Herbert R. Northrup added another narrative on discrimination to Doeringer’s account. In “The racial policies of American industry,” in the July issue, he analyzed the rationales of employer policies with an eye toward understanding why some industries, and some companies within an industry, “are more hospitable to minority group employment than are others.” Without offering any answers, he proposed testing 11 hypotheses bearing on the racial policies of employers. The findings, he suggested, “combined with labor market analysis and trends and with business and job forecasting, would permit a more rational attack on discrimination in employment.” Whether his hypotheses bore fruit may or may not be ascertainable from his numerous publications.

With the arrival of 1968, the Review continued its coverage of the momentous societal transformation that was taking place in the nation in regard to civil rights, poverty, and the Great Society. In the February issue, Harvey R. Hamel discussed the “Educational attainment of workers,” focusing on the disparity in educational attainment between African Americans and Whites, a disparity that led, and still leads, to differences in the two groups’ occupational distribution and to higher unemployment rates for African Americans. Hamel brought to the reader’s attention the fact that average educational attainment had risen considerably in the United States from 1952 to 1967. But the effect was disparate: although both Blacks and Whites had increased their educational attainment (and, indeed, Blacks had done so at a faster pace than Whites), the representation of the two groups in the U.S. occupational distribution was quite different. Hamel found that, in general, White workers had a greater representation in “the more desirable occupations” while Black workers were “overly concentrated in less preferable jobs.” Specifically, in March 1967, half of White men, but only a fourth of African American men, were employed in professional and technical jobs, in managerial occupations, or as officials, proprietors, or skilled craftworkers. In contrast, African American men were overrepresented in semiskilled and unskilled blue-collar jobs and in service occupations. But perhaps the most important of Hamel’s findings was that “variations in levels of educational attainment alone [were] not sufficient to explain the…occupational differential.” Using quantitative techniques, he showed that the expected number of Black men working in each occupation studied, assuming full equality of employment opportunity at each education level, was substantially (and perhaps significantly—Hamel gave no estimates of statistical significance) above the actual number working in that occupation. He concluded that the difference in the proportions of White men and Black men working in the various occupations was attributable, “not to an education effect but to other factors such as employment discrimination, inferior quality of education, residence, lack of capital to enter business, or inability…to obtain jobs commensurate with their education levels.”

As the decade of the 1960s came to a close, Hazel M. Willacy brought the social and job problems still facing poor African American (as well as poor White) men into perspective with her 1969 Review article “Men in poverty neighborhoods: a status report.” Despite the achievements of the Civil Rights Movement, the War on Poverty, and the Great Society, much remained to be done for the “significant proportion of the Nation’s men [who] live[d] in poverty and degradation.” Recounting the reasons these individuals were “unable to fulfill their role of family breadwinner,” Willacy cited “health problems, low educational attainment, their previous work experience, discrimination, [and] the lack of suitable job opportunities.” All these factors resulted in the chief problem confronting men living in poverty neighborhoods: inadequate earnings, even though most of the men residing in those neighborhoods were employed. The reasons for their inadequate earnings were both manifold and familiar, running the gamut from being confined to part-time jobs because of slack work, shortages of materials, or inability to find full-time employment; to finding work only in unskilled, semiskilled, or low-paying service jobs; to failing to get financial backing for self-employment. In keeping with the Review’s mandate of being policy neutral, Willacy offered no solutions to these problems.

The 1970s. The decade of the seventies opened with the Review continuing to report on poverty and (by now the aftermath of) the Civil Rights Movement. In the June 1970 issue, Hazel M. Willacy and Harvey J. Hilaski coauthored an article on the status of “Working women in urban poverty neighborhoods.” Asserting that the problems associated with these neighborhoods fell most heavily, in increasing order, on women, working women, and African American working women (many of whom were single heads of households), the authors found, as many had before, that “less skilled, intermittent, and often low-paying jobs” were what kept those women in poverty. One statistic stood out in particular: almost 20 percent of African American women living in urban poverty neighborhoods were private household workers, whereas just 3 percent of White women residing in those same neighborhoods were. Then, in an article on “Differentials and overlaps in annual earnings of blacks and whites” in the June 1971 issue, Arnold Strasser pointed out that, despite significant differences, there was a considerable overlap between Blacks and Whites in the earnings distribution. The article was, in effect, a counterpoint to what Hamel had found in his 1968 analysis of the occupational distribution. In that piece, Hamel showed that White workers were overrepresented in what he called “the more desirable occupations” while Black workers were overrepresented in “less preferable jobs.” He counted professional and technical jobs, managerial occupations, officials, proprietors, and skilled craftworkers among the more desirable occupations. Jobs he saw as less preferable were semiskilled and unskilled blue-collar jobs and service occupations. The difference in representation in the occupational distribution would, of course, likely lead to a difference in the earnings distribution, with Black workers tending toward the bottom because of their lesser earnings from the “less preferable jobs.” In a novel approach, however, Strasser showed that, although, in general, that was true, the overall picture obscured the fact that, when the percentages of Black and White workers who fell within the same earnings brackets were compared, 71 percent of men and 83 percent of women of each race had identical earnings. Thus, the earnings disparity between the two races was due entirely to the 29 percent of men and 17 percent of women whose earnings fell outside the area of overlap: Black workers whose earnings were outside the overlap area were in the lower earnings categories, while White workers whose earnings were outside were in the higher earnings categories. Strasser concluded on an optimistic note: recent changes indicate that “it is reasonable to assume that there has been a narrowing in the earnings differential between blacks and whites and a concomitant increase in the distributional overlap of earnings of blacks and whites.”

In the May 1972 issue of the Review, Herbert Hammerman reported on “Minority workers in construction referral unions.” Viewing unions as an important factor in increasing employment and job security for minorities, Hammerman discussed one type of union—the construction referral union—and the role it was playing in locating and advancing employment opportunities for minorities. Set up as a helpful conduit to employment for craftworkers in various industries (e.g., construction, transportation, trade, and manufacturing), the typical referral union represented “workers in one or more trades, such as electricians, carpenters, plumbers and pipefitters, …, truckdrivers, waiters, and building service employees.” The jobs of these workers varied widely, but shared a number of characteristics: they were “casual, intermittent, and of limited duration,” offered “fluctuating work opportunities,” and were performed “at scattered and varied worksites.” As Hammerman explained, “Without unionization, these conditions of employment lead, almost inevitably, to great day-to-day job insecurity.” The issue posed in the article was whether one particular type of referral union—the construction referral union—served minority workers effectively. After substantial analysis, he concluded that, although, in general, minorities either were overrepresented (Hispanics and Native Americans)9 in that union, with double their proportions in industry as whole, or had about the same proportion of members as they had in industry (Blacks), all of them were underrepresented in high-skill, high-paying trades represented by companies with which the unions collectively bargained. In particular, noted Hammerman, “if black membership in the 12 internationals of the mechanical trades and the miscellaneous construction trades had reached…the level of 5 percent in 1969, it would have been 30,000 greater than it was….Such [a] modest goal would seem to be attainable [through] training,…affirmative action programs, and litigation under the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972.”

Hispanics occupied the forefront of the Review’s pages among minorities in April of 1973, with two articles demonstrating that the concerns of the War on Poverty reached minorities other than African Americans: Paul M. Ryscavage and Earl F. Mellor’s “The economic situation of Spanish Americans” and “Factors affecting the job status of workers with Spanish surnames,” by Jerolyn R. Lyle. In the first, Ryscavage and Mellor found that low pay, high unemployment, few marketable skills, and the language barrier presented by English were depressing the incomes of Hispanics.10 The authors traced these disabling factors largely to relatively low educational attainment, with the median years of schooling completed by Hispanic people 25 years and older just 9.6, compared with 12.1 for the total U.S. population. A reason for optimism for the future, however, was that 9 out of 10 Hispanic youths and young adults ages 10 to 24 reported that they could read and write English. In the second article, Lyle, apprehending that “Spanish-surnamed workers [were] at a significantly lower rung on the occupational ladder than other white (“Anglo”) workers,” developed a model to test the relative importance of factors affecting the behavior of employers and factors outside the employment context in an attempt to explain the higher proportion of Hispanic workers in the lower paying occupations. Hypothesizing that the problem was the presence of one or more factors presenting a barrier to the upward mobility of Hispanic workers, she classified the possible factors into two categories: those which were likely to affect the employer’s behavior (e.g., unionization, local attitudes toward equality for minorities) and those which were not (e.g., the worker’s educational attainment and access to public transportation). Then she performed two regressions, one by industry and one by Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area. The results were telling: in the regression by industry, none of the factors that were not likely to affect the employer’s behavior were significant in impeding the upward mobility of Hispanic workers, especially for men, but also, to a lesser extent, for women; in the regression by Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area, the results were mixed, with the factors that were likely to affect the employer’s behavior (as well as some that were not) playing a significant role in impeding the upward mobility of both men and women. Lyle concluded that “factors directly affecting the behavior of the employer are of more significance vis-à-vis the occupational status of the Spanish-surnamed worker than factors relating to the worker himself or to the community.” The implication was that changes in corporate policies and processes would be more likely to lower barriers to advancement for Hispanic workers than would policies designed, for example, to improve education or transportation in large cities.

The June 1974 issue featured an article with the intriguing title “Black studies in the Department of Labor, 1897–1907,” by Jonathan Grossman, a social science advisor in the U.S. Department of Labor and a professor of labor history at the University of Maryland. The article offered the reader a retrospective look at a little-known turn-of-the-century groundbreaking effort of the Department that brought the condition of African Americans in the United States to the attention of the American public—perhaps for the first time in such a concerted, deliberate manner by a federal agency. Although not entirely transparent, evidence indicates that George G. Bradford, a Boston businessman and trustee of Atlanta University from 1895 to 1902, and Horace Bumstead, also of Boston, and president of Atlanta University from 1888 to 1907, originated the idea of having the university carry out a systematic study of “the physical and moral condition of city blacks” and then have the Department, under then–Commissioner of Labor Carroll D. Wright, tabulate the results and publish them jointly with the university. Their combined efforts culminated in the publication of nine investigations over the timespan mentioned in the title of the Review article. A chief contributor to the studies, penning three of them, was the distinguished Black scholar and social activist W. E. B. Du Bois, like Bradford and Bumstead, originally from Massachusetts. The studies covered a host of topics, but their chief thrust was to bring to light both the differences and the similarities of Blacks living in different circumstances in different U.S. locales, from Farmville, Prince Edward County, Virginia; to the “Black Belt” of the South, encompassing a swath of territory in what are today portions of the Census South Atlantic, East South Central, and West South Central Divisions; to the community of Sandy Spring, Maryland, settled largely by Quakers who emancipated their slaves even before the Civil War; and more. Ultimately, the Department and the university parted ways, and the effort was abandoned, a victim of the then-prevalent climate of racial strife left over by the Civil War, the failure of Reconstruction, and the decision in Plessy v. Ferguson establishing “separate but equal” facilities in the South. The latter in particular made the “[c]alm discussion of [the] economic and social conditions of blacks…difficult.” Charles P. Neill, appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt to succeed Commissioner Wright in 1906, lost interest in the Black Studies program and ended it in the midst of a shortage of money and the demotion of the Department of Labor to a bureau within the newly created Department of Commerce and Labor. Still, the legacy of the relatively short-lived program remains in its nine publications, genuine contributions to the literature on Blacks in America.

Like 1973, the year 1975 saw two Review articles on the situation of Hispanics in the nation. Two subgroups of Hispanics were the focus this time: Mexicans and Puerto Ricans. In “Immigrant Mexicans and the U.S. work force,” in the May issue, Walter A. Fogel pointed out the dilemma that Mexican immigrants—including, and even especially, illegal immigrants—presented to the U.S. labor market: their work, at one and the same time, resulted in “lower wages and prices and greater employment and output than would exist in the absence of these workers; also less unionization and greater income inequality.” Singling out illegal immigrants, he said, “The match between illegal Mexicans and secondary markets is particularly good.”11 Characterizing illegal immigrants as having little skill; needing a job quickly; being, of necessity, docile workers; and being unlikely to continue employment for very long, Fogel said, “The last characteristic makes him particularly suitable for seasonal employment. He not only accepts layoffs unquestioningly, but also returns to Mexico in most instances and, consequently, exerts no demand on community social services. Because of these characteristics, he represents almost an ideal labor supply to some U.S. farm employers.”

In the second article, “The jobs Puerto Ricans hold in New York City,” appearing in the October issue, Lois S. Gray learned from the 1970 census that most Puerto Ricans living in New York that year held blue-collar jobs and suffered higher-than-average unemployment. Just 33 percent of the city’s Puerto Rican workers were in white-collar jobs, compared with 58 percent of all city workers. Still, the percentage was a marked improvement over the 1960 figure of almost 19 percent. Typical private industry jobs held by New York City Puerto Rican men were in manufacturing, where many were textile and metalworking operators and painters of manufactured products; transportation, in which many drove taxis and buses; retail trade, in which they served as meatcutters, packers, and wrappers; and service, where they accounted for one-fifth of dishwashers and dining room attendants. New York City Puerto Rican women typically held jobs as service workers in laundry and drycleaning establishments; graders, sorters, sewers, and stitchers in the apparel industry; hairdressers in retail establishments; and nursing aides in the healthcare industry. In the public sector, the patterns were similar. Of note, Gray observed that there were “many more professional and managerial opportunities for Puerto Ricans on the island than on the mainland” and “Puerto Ricans who return to the island after acquiring mainland experience often move from blue-collar to white-collar employment.” Migration to the mainland was thus seen as a double-edged sword, entailing a risk of downward mobility for the highly skilled but offering the prospect of upward mobility for those with little skill or work experience.

Part of the landscape of the civil rights struggle of the 1960s and 1970s was the women’s movement. The Review, of course, had published many articles on women’s issues (see part I of this series for a number of examples during the early years), but the new fervor felt in the sixties and seventies for the cause of women reached far into the publications world. The Women’s Bureau of the Department of Labor, established in 1920, saw its first African American woman, Elizabeth Duncan Koontz, elected in 1969, and with her tenure came an increased emphasis on eliminating discrimination against women in the workforce. The Review reflected this emphasis in numerous articles published over the period. Two special sections in particular confronted the problem of workplace discrimination and the associated challenges that women faced. In the June 1970 issue, the section “Women at work” featured the article “Reducing discrimination: role of the Equal Pay Act,” by Robert D. Moran, in which the author both lauded the passage by Congress of the groundbreaking Equal Pay Act of 1963 and decried the attempts by employers to thwart it on a number of (usually transparent) pretexts. As an example of what the act had achieved, Moran cited one court decision that awarded 230 women who were doing essentially the same job as men, but under a different job title, a substantial amount of backpay, plus an increase in their hourly wage to bring their wages to parity with those paid the men.12 In his ruling in the case, Chief Judge Abraham Freedman poignantly stated that the Equal Pay Act was designed “as a broad charter of women’s rights in the economic field” and “sought to overcome the age-old belief in women’s inferiority and to eliminate the depressing effects on living standards of reduced wages for female workers and the economic and social consequences which flow from it.”13

The second special section, titled “Women in the workplace,” appeared in the May 1974 issue of the Review. In it, Janice Neipert Hedges and Stephen E. Bemis touted some of the progress made in combating gender stereotyping on the job since the passage of the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Their article, “Sex stereotyping: its decline in skilled trades,” related how a January 1973 consent decree between the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T), on the one hand, and the Department of Labor and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, on the other, spurred AT&T and, later, other employers to adopt a series of “affirmative action” personnel policies aimed at ending the gender stereotyping of jobs. Among the policies adopted were goals and timetables for placing women in skilled jobs and management-level positions. No longer would the discrimination afforded by gender stereotyping be permitted: employers found guilty of violating the decree would be fined. Hedges and Bemis went on to report that, as a result of the decree and the passage of all the associated governmental legislation, “in 1970 almost half a million women were working in skilled occupations, up from 277,000 in 1960.” The rate of growth, about 80 percent, was double the rate of growth for women in all occupations and 8 times that of men in skilled occupations. The ramifications touched many aspects of women’s lives, from the social, to the legal, to the economic, to the psychological—and the future, maintained the authors, was rosy: “The employment of women in the skilled trades can be expected to increase, as widespread reappraisal and rejection of the sex stereotyping of jobs are reflected in institutional changes.”

Lest one think that such a future was assured, another article in the series, “Where women work—an analysis by industry and occupation,” by Elizabeth Waldman and Beverly J. McEaddy, alluded to the notion that progress, though perhaps steady, might be slow. Analyzing data from three sources—the payroll or establishment (Current Employment Statistics) survey, the household survey (Current Population Survey), and decennial censuses from 1940, 1950, 1960, and 1970—the authors concluded that, like men, women found jobs in the fastest growing industries, but unlike men, they remained clustered in just a few occupation groups. Throughout those decades, both the number and percentage of women employed in nonagricultural industries grew steadily until, by 1970, women in the labor force numbered about 27.5 million and made up 40 percent of the workforce. Yet, no matter the industry, women found employment in fewer occupation groups than men. In the service industry—the industry that employed the largest number of women in each of the census years examined—women were employed mostly as elementary and high school teachers, nurses, social workers, and librarians, all relatively low-paying occupations. In government, women held jobs as teachers, administrators, clerical workers, maintenance workers, and librarians. About 77 percent were in the lowest paying jobs, at grade levels GS-1 through GS-6, while another 20 percent were at grade levels GS-7 through GS-11. Only 3 percent held jobs at grade levels GS-12 and above. In trade, nearly 90 percent of women were in retail trade, where low-paying sales, clerical, and service jobs predominated; women who worked in eating and drinking establishments were mostly waitresses, cooks, and clerical workers, again low-paying jobs. In manufacturing, 60 percent of women were employed in the low-paying production aspect of the industry, as operatives, checkers, examiners, and inspectors, and as sewers and stitchers. Despite some inroads made over the decades that followed, the overall situation would persist even until the present: in 2013, women still were the majority of workers in many low-paying occupations and their earnings remained considerably less than that of men.14

Economically, the 1970s ended on a discordant note, with 1979 average inflation at 11.3 percent, the highest seen since 1947 (14.4 percent).15 The Review carefully observed the upward spiral throughout 1978 and 1979, reporting monthly numbers in “Current labor statistics,” a regular section since July 1947, and publishing annual and quarterly features covering the rapidly deteriorating situation. In the annual feature, the February 1978 article titled “Price changes in 1977—an analysis,” by Toshiko Nakayama, Craig Howell, Paul Monson, and William Thomas, foreshadowed what was to come, noting that in 1977 the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 6.8 percent after having fallen to a 4-year low in 1976. Then, over the last 7 months of 1978, Nakayama, Howell, and Monson added three installments in “The anatomy of price change” feature. In the first, “Food prices lead acceleration of inflation in first quarter” (June), they reported a 9.3-percent increase in the CPI during the first quarter of the year—a rise almost twice as fast as that in the second half of 1977. In the second installment, “Double-digit inflation returns in second quarter” (September), those same authors saw inflation rates returning to those encountered during the foray of the CPI into rates 10 percent and higher from February 1974 through April 1975. Finally, in the third installment, “Slowdown in food prices curbs inflation in third quarter” (December), Nakayama and Howell reported that the inflation rate had moderated briefly from July through September.

The annual feature's March 1979 entry, “Price changes in 1978—an analysis,” by Craig Howell, William Thomas, Walter Lane, and Andrew Clem, reported an inflation rate of about 9 percent over the year, more than at any time since 1974—and things didn’t appear to be getting any better, as evidenced by the title alone of an article penned by Howell, Thomas, and Eddie Lamb in June 1979: “First-quarter food and fuel prices propel inflation rate to 5-year high.” Commenting on the inflation scenario were two June 1979 articles about the effects of rising inflation on wages and the cost of living. In one, titled “Wage increases of 1978 absorbed by inflation,” Joan D. Borum hailed the large over-the-year pay increases for most workers, but then lamented that the raises failed to keep pace with price increases. “As a result,” she said, “the average American worker experienced a decline in purchasing power.” In the other article, “Cost-of-living adjustment: keeping up with inflation?” Victor J. Sheifer bemoaned the failure of collectively bargained escalator clauses to protect the worker against the higher prices seen in 1978; that year, said Sheifer, average cost-of-living adjustment yields met just 57 percent of the increase in prices that was due to inflation. Then, in a September 1979 summary labor force report titled “Energy buoys double-digit inflation, food price surge ebbs in second quarter,” Howell, Clem, and Lamb attested to the continuing downbeat inflation situation, observing that “the substantial deceleration in food price increases” was not enough to offset the “upsurge in prices for energy-related items during the second quarter of 1979.” In December 1979, “The anatomy of price change” feature returned, with Howell, Thomas, and Lamb reporting, “Consumer prices rise at 13-percent rate for the third consecutive quarter.” Workers were losing ground to inflation, and the scene was set for 2 years of steadily eroding consumer purchasing power as the 1970s drew to a close.

The period 1930–80 saw unprecedented economic and political events that steered the discourse in the Review. A notable shift in publication coverage from the early years was the greater emphasis on topics related to poverty, organized labor, and race and gender issues. As will be demonstrated in part III of this series of articles, these themes, supplemented with new ones, continued to receive attention in subsequent decades.

Brian I. Baker, "The Monthly Labor Review at 100—part II: the “middle years,” 1930–80," Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2016, https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2016.22

1 This section owes much to Phyllis Groom’s insightful, engaging article “From Model-T to Medicare—paragraphs from history,” Monthly Labor Review, July 1965, pp. 778–786.

2 See “Employment statistics and conditions: conditions in families of the unemployed in Philadelphia, May 1932,” Handbook of Labor Statistics, Bulletin 616 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1936), pp. 184–186, especially table 1, p. 184.

3 Groom, “From Model-T to Medicare,” p. 782.

4 Louise E. Howard, Labour in agriculture—an international survey (London, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1935).

5 From 1947 to 1957, the annual average unemployment rate varied from a low of less than 3 percent in 1953 to a high of 5.9 percent in 1949, averaging about 4.2 percent over the period. (See “Databases, tables, & calculators by subject” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics), https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNU04000000?years_option=all_years&periods_option=specific_periods&periods=Annual+Data.)

6 See Gerald Mayer, Union membership trends in the United States (Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress, August 31, 2004), especially “Summary,” at beginning of document (no page number), https://hdl.handle.net/1813/77776.

7 “Ostensibly” because, as an apolitical agency, BLS does not prescribe policy. However, it is not precluded from reporting on theories or other matters that may have policy consequences.

8 See Mayer, Union membership trends in the United States, especially figure 1, “Union membership as a percent of employment, 1930–2003."

9 Hammerman used the terms “Spanish American” and “American Indian,” both fallen into disuse today.

10 Like Hammerman before them, Ryscavage and Mellor used the term “Spanish American” to denote the ethnic group that we might today call Hispanics.

11 Secondary markets are markets characterized by high turnover, low pay, and usually part-time or temporary work.

12 Shultz v. Wheaton Glass Co. (C.A. 3, January 3, 1970), 421 F.2d 259.

13 Ibid.

14 See “30 leading occupations for employed women by selected characteristics (2013 annual averages),” Leading occupations (U.S. Department of Labor, Women’s Bureau).

15 See “Table of historical inflation rates by month and year,” Historical inflation rates: 1914–2016 (San Antonio: Coinnews Media Group, January 20, 2016), http://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/historical-inflation-rates.