An official website of the United States government

United States Department of Labor

United States Department of Labor

For its seasonally adjusted data, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) seeks to remove all fluctuations that are caused by the yearly cycle of seasons. The coronavirus 2019 pandemic posed a challenge to this task, because its effect was strong, across the entire economy, and lasted for at least several months. To ensure that the effects of the pandemic were not being incorporated into the seasonal adjustment factors, the Current Employment Statistics program took additional actions such as splitting the seasonal adjustment into two runs (prepandemic and postpandemic) and incorporating additional types of outliers into its models.

Most series published by the Current Employment Statistics (CES) program have a regularly recurring seasonal movement that can be measured from past data. Seasonal adjustment eliminates the part of the change attributable to the normal seasonal variation to help provide a better interpretation of trends without the influence of regularly occurring seasonal patterns. Previous publications from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) have discussed the challenges of seasonal adjustment during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Those publications focused on the approaches BLS has taken to mitigate the effects of the pandemic on the real-time seasonal factors BLS uses to produce the seasonally adjusted series.1 Those discussions address how we use outlier detection, our most commonly used tool, to intervene in realtime when we estimate seasonal factors each month.

COVID-19 had a dramatic effect on the labor market. Unlike a strike or weather event, the effect was nationwide and, for some industries, sustained over a long period. BLS needed to carefully construct its seasonal adjustment models to ensure that the effect of the pandemic did not get incorporated into the models as a normal seasonal fluctuation. This article addresses how the CES program seeks to mitigate the effects of the pandemic on the 5 years of historical seasonal factors that are revised annually for the CES program. To preserve the accuracy of the historical seasonally adjusted data in response to the effects of COVID-19, BLS combined a sequence of two runs (prepandemic and postpandemic) as an additional intervention, along with the normal outlier-detection treatment, to produce the revised series for the 2020 annual review. Since the time of the 2020 annual review, BLS time-series researchers have developed responses that provide a more standardized approach to mitigating the effects of the pandemic. This article also addresses the procedure used during the 2021 annual review, which includes the use of additional outlier types discussed in the responses developed by these researchers.

The CES program is a monthly survey conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The program provides employment, hours, and earnings estimates based on payroll records of business establishments. Data produced from the CES survey include nonfarm employment series for all employees, production and nonsupervisory employees, and women employees, as well as average hourly earnings, average weekly hours, and average weekly overtime hours (in manufacturing industries) for both all employees and production and nonsupervisory employees.

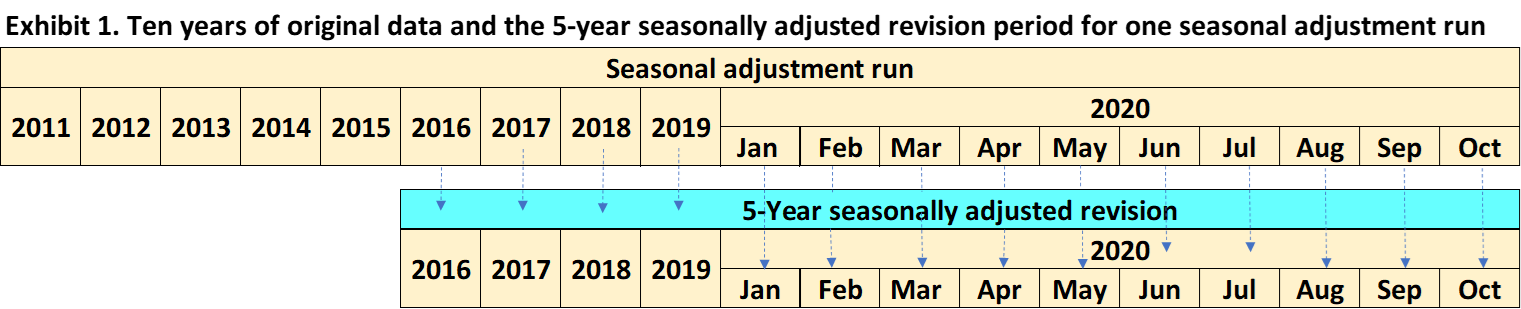

Each year, BLS examines and revises the previous 5 years of seasonal factors and seasonally adjusted data that were originally calculated in realtime. The CES program uses 10 years of original data to produce seasonally adjusted data. Once a year, the CES program selects new model specifications and recalculates the previous 5 years of seasonally adjusted data using the new model specifications.2 The model specifications selected annually are not changed until the next annual review. After 5 years, the CES program no longer revises the seasonally adjusted series, unless there is a change to the industry that requires a reconstruction of the time series.3

Prior to the normal treatment for seasonal adjustment, CES analysts remove quantifiable nonseasonal events, such as strikes, from the original data to ensure that those events are not included in the calculation of the seasonal factors. Additionally, X-13ARIMA-SEATS, the seasonal adjustment program BLS uses to produce seasonally adjusted data, detects outliers.4 The seasonal adjustment program removes the outliers detected and does not use them in calculating the seasonal factors. Removing the outliers detected prevents extreme values from distorting the seasonal factors. The seasonal adjustment program removes the outliers from the calculation of the seasonal factors but not from the seasonally adjusted series. After the seasonal adjustment program calculates the seasonal factors, it applies them to the original data to calculate the seasonally adjusted series. The seasonally adjusted series is the trend and the irregular components combined, which includes the outliers. CES analysts then uses the new model selections to revise the most recent 5 years of seasonally adjusted data. Exhibit 1 provides the historical time frame of the original series, used to produce the seasonally adjusted data, and the latest revision period that would be used in the normal treatment process.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an event that has affected just about every part of the economy to such a degree that we now define many aspects of what we do into a prepandemic (prior to February 2020) and postpandemic (March 2020 forward) time frame. Given the pandemic, the CES program had to determine how best to maintain the integrity of the seasonally adjusted history prior to the pandemic. This task was particularly challenging in that the effects of the pandemic should not influence the seasonal adjustment model used to generate the seasonal factors that are prior to the pandemic. Ordinarily, outlier detection alone is used to prevent extreme values from affecting the calculation of the seasonal factors. However, additional intervention was necessary because of the extreme, pandemic-induced fluctuations in the estimates and the extended time frame over which the pandemic has occurred. The results provided show that, even with the outlier detection used as part of the normal treatment process, there were larger than normal revisions to the historical time series and unexpected changes to the historical normal seasonal movements.

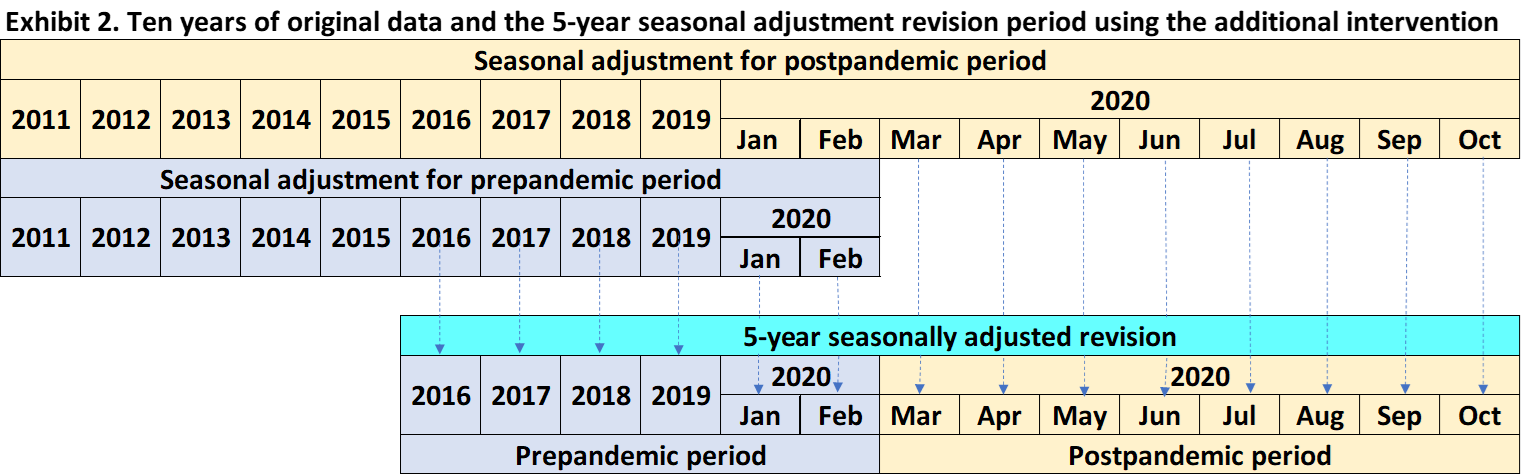

To address these issues, CES analysts ran a sequence of two runs (prepandemic and postpandemic) for the purpose of mitigating the effect of the pandemic on the calculation of the historical seasonal factors. Informed by the combination of these two sequential runs, the CES program revised 5 years of seasonally adjusted data. Exhibit 2 provides the time frame of the original data BLS used to produce the seasonally adjusted data and the revision period of the latest annual review with the additional intervention. The revised seasonally adjusted data prior to March 2020, when the pandemic began, were produced from the prepandemic run. The revised seasonally adjusted data after the pandemic began, in March 2020, were produced from the postpandemic run. BLS used this combined approach to ensure that the effects from the pandemic were limited to the pandemic months and did not affect the seasonally adjusted history prior to the pandemic.

To better understand historical seasonal patterns, it is useful to view the normal seasonal movement in a series over time. The normal seasonal movement is calculated as the difference between the month-to-month change in the original, not seasonally adjusted series minus the month-to-month change in the seasonally adjusted series:

![]()

The normal seasonal movement is useful for analyzing historical seasonal patterns because it provides a rough estimate of the strength of the seasonal effect over time. The normal seasonal movements of the total employment series using the normal treatment are compared to the normal seasonal movements of the published total employment series using the additional intervention to show the effects of using the additional intervention as compared to the normal treatment.

Chart 1 highlights the normal seasonal movements of total nonfarm employment over time for March, one the months hit hardest, economically, by the pandemic. The rightmost bar in each year shows the normal seasonal movements as previously published before the annual review. In March of each year from 2011 to 2019, employment has increased by approximately 500,000–600,000 on account of the normal seasonal movement. In contrast, the previously published normal seasonal movement for March 2020 was 360,000, much lower than normal. This weakness comes from the effects of the pandemic without any additional intervention to mitigate them. The middle bar of the chart shows a similar pattern in the normal seasonal movements calculated with the normal treatment. As a result of the revision, the weakness from the effects of the pandemic is spread over the previous 5 years in addition to March 2020. The leftmost bar in each year of chart shows the normal seasonal movements revised 5 years using the additional intervention. The normal seasonal movements with the additional intervention are more stable and consistent with the history prior to the influence of the pandemic. Next, the results for the prepandemic period and the postpandemic period are discussed to explain the effects of the additional intervention compared with the normal treatment in more detail.

| Year | Additional intervention | Normal treatment | As previously published |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avg (2011-2015) | 679.2 | 679.2 | 679.8 |

| 2016 | 660 | 605 | 668 |

| 2017 | 521 | 528 | 531 |

| 2018 | 513 | 488 | 532 |

| 2019 | 508 | 443 | 529 |

| 2020 | 670 | 474 | 360 |

The normal seasonal movements in the prepandemic period, from January 2016 to February 2020, show that the additional intervention provides more consistency and smaller revisions compared with the results from the normal treatment. This is especially visible in the history of the series in the months of March and April. Without the additional intervention, the historical normal seasonal movements show a weaker seasonal increase than the previously published data. This weakening is due to the seasonal adjustment process factoring the effects of the pandemic into the history. The normal seasonal movements resulting from the additional intervention are more consistent with the previously published historical seasonal movements.

In the first month of the postpandemic period, March 2020, the expected seasonal increase made using the normal treatment appears to have been weakened by the effects of the pandemic. Using the additional intervention shows a larger revision more in line with the previously published data compared to the normal treatment, which appears to have shifted the weakness from the pandemic back into the historical normal seasonal movement. The estimates for the remainder of the postpandemic period from April 2020 forward are the same between the normal treatment and the additional intervention because all 10 years of data through October 2020 were used to calculate the seasonal factors for both approaches.

The two-step approach used during the 2020 annual review addressed the need to mitigate the effects of the pandemic in realtime with a limited amount of data. Now that we have more data available and additional guidance on using outlier intervention options within the X-13 ARIMA-SEATS software, CES has moved toward using a more standardized approach.

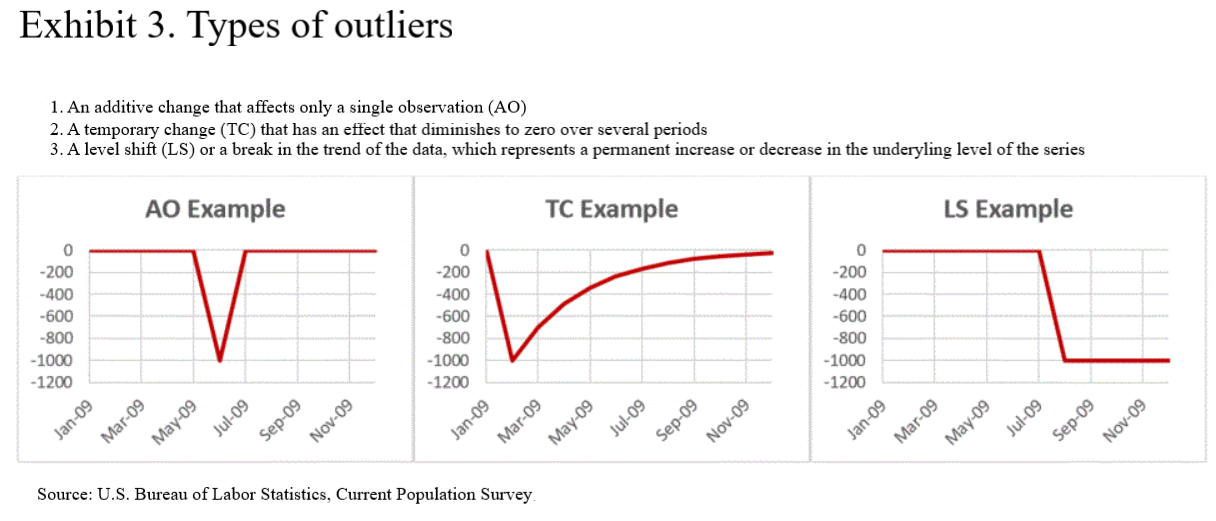

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, BLS time-series researchers developed several responses to the challenges. They found that using additional outlier types could provide a more parsimonious outlier set for the pandemic period.5 Using additional outlier types provides users the simplest model with the least variables and greatest explanatory power. Additionally, there are a number of CES series with complex movements during the pandemic period that could not be adequately adjusted by using the additive outlier types only.

For 2021's annual review, two approaches were evaluated:

Exhibit 3 provides details on the different outlier types:

To compare model fits, the CES program uses a version of the Akaike information criterion (AIC). From Rebecca Bevans of Scribbr, "The Akaike information criterion is a mathematical method for evaluating how well a model fits the data it was generated from. In statistics, AIC is used to compare different possible models and determine which one is the best fit for the data. AIC is calculated from:

The best-fit model according to AICc is the one that explains the greatest amount of variation using the fewest possible independent variables."6

The CES program uses the AIC corrected for small sample sizes, the AICc. As such, the AICc is used here to determine which outlier treatment provides the best model fit. Like the AIC value, a lower AICc value is an indicator of a better fit model. Table 1 provides a comparison of the number of series with a lower AICc from the model using the normal treatment with AOs only against those of the additional-treatment model using all outlier types.

| CES series | AICc lower (better model fit) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All outlier types | AO only | Total number of series | |||

| Number of series with better fit | Percentage of series with better fit | Number of series with better fit | Percent of series with better fit | ||

| Total | 2,363 | 48 | 2,555 | 52 | 4,918 |

| All employees | 571 | 68 | 263 | 32 | 834 |

| Average weekly hours for all employees | 233 | 37 | 404 | 63 | 637 |

| Average hourly earnings for all employees | 215 | 34 | 422 | 66 | 637 |

| Average weekly overtime hour for all employees | 43 | 35 | 79 | 65 | 122 |

| Production employees | 435 | 68 | 202 | 32 | 637 |

| Average weekly hours for production employees | 218 | 34 | 419 | 66 | 637 |

| Average hourly earnings for production employees | 201 | 32 | 436 | 68 | 637 |

| Average weekly overtime hours for production employees | 40 | 33 | 82 | 67 | 122 |

| Women employees | 407 | 62 | 248 | 38 | 655 |

| Note: AO = Additive outliers. AICc = Akaike’s information criterion (corrected for small sample size). CES = Current Employment Statistics. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |||||

We found that, overall, the number of series with a better model fit when we used all outlier types (48 percent of series) is approximately the same as those with a better model fit when we used the AO-only outlier types (52 percent). However, there are substantial differences in these numbers by data series type. For the employment series, the model using all outlier types provided a better fit for most series: all employees (68 percent of series), production employees (68 percent), and women employees (62 percent). The pandemic most strongly complicated the behavior of the employment series, which required additional outlier types to fully adjust. For the hours and earnings series, the model using AO-only outliers provided a better fit for most series. The impact from the pandemic on the hours and earnings series were less substantial in most cases and do not require the additional outlier types to provide a better model fit. The model with the lower AICc was used to produce the seasonally adjusted data for each series. Additionally, CES analysts performed a review of the series on a case-by-case basis to validate the seasonally adjusted series as part of the usual annual review procedure.

The normal seasonal movements in the prepandemic period, from January 2017 to February 2020, show that including the additional outlier types provides more consistency and smaller revisions compared with the normal treatment that uses the AOs only. The smaller revisions are broadly visible throughout the history of the series. Without the use of the additional outlier types, the historical normal seasonal movements show a weaker seasonal increase than those previously published. This weakening is due to the seasonal adjustment process incorrectly factoring the effects of the pandemic into the history as normal seasonal movement. The normal seasonal movements calculated with the additional outlier types are more consistent with the previously published historical seasonal movements.

The normal seasonal movements in the postpandemic period, from March 2020 to October 2021, show that including the additional outlier types provides more consistency and smaller revisions compared with the normal treatment that uses the AOs only. In the first month of the postpandemic period, March 2020, and in the following March 2021, the expected seasonal increase calculated with the AOs only appears to have been weakened by the effects of the pandemic. Using the additional outlier types shows a normal seasonal movement more in line with the previously published history compared with the results from the AOs only model, which appears to have shifted the weakness from the pandemic back into the historical normal seasonal movement. The revisions to March 2020 through the remainder of the postpandemic period are consistently smaller when including the additional outlier types.

The COVID-19 pandemic is unusual in its severity and duration when compared with other shocks to the economy. As a result, additional intervention was required to preserve the accuracy of the historical seasonally adjusted series. The results show that the effects of the pandemic were not completely removed from the seasonal factors as part of the normal treatment in which we used additive outlier detection alone. As part of the 2020 annual review, additional intervention and a sequence of two runs (prepandemic and postpandemic) was used to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on the historical seasonal factors. The additional intervention is an extension of the normal outlier-detection treatment and is an additional step towards effectively isolating the prepandemic period. The point of the additional intervention is to ensure that the postpandemic period does not influence the seasonal model prior to the pandemic—so that we preserve the historical seasonal patterns. The results show that the historical normal seasonal movements calculated with the the additional intervention are more in line with the expected normal seasonal movement—especially in the months in which the pandemic had its largest economic effect (March and April 2020). This approach provided the most accurate revisions to the seasonally adjusted data in realtime with the limited amount of postpandemic-period data available during the 2020 annual review just after the start of the pandemic. As the pandemic unfolded, BLS time-series researchers were able to develop a more standardized approach to mitigating the effects of the pandemic. In lieu of using the two-step approach used during the 2020 review, CES incorporated the use of additional outlier types available in the X-13 ARIMA-SEATS software as part of the most recent annual review to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. The models available by the use of the additional outlier types provide a better fit and allow better adjustments for the complex movements in the CES series that are due to the pandemic. These new models result in the calculation of more stable seasonal factors used to produce the seasonally adjusted series.

The appendix provides the components used to calculate the normal seasonal movement for total nonfarm employment for the following:

Tables A-5 through A-7 provide the normal seasonal movements calculated using the components from Tables A-1 through A-4. The difference in the normal seasonal movement between the normal treatment and the additional intervention is provided in table A8. The difference between the normal seasonal movement as previously published and the revised normal seasonal movement calculated by means of the normal treatment and the additional intervention is provided in tables A-9 and A-10, respectively. Some months are affected by the variable survey week adjustment, sometimes referred to as the 4- versus 5-week effect.7

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | -2,863 | 814 | 906 | 1,2171 | 684 | 4891 | -1,274 | 275 | 7461 | 923 | 335 | -1751 |

| 2012 | -2,606 | 9541 | 904 | 883 | 814 | 3371 | -1,209 | 3791 | 628 | 847 | 3891 | -75 |

| 2013 | -2,882 | 1,0381 | 799 | 1,005 | 8931 | 409 | -1,174 | 4371 | 608 | 922 | 5251 | -251 |

| 2014 | -2,8041 | 740 | 958 | 1,138 | 9121 | 587 | -1,079 | 3801 | 686 | 1,0541 | 465 | -4 |

| 2015 | -2,8151 | 831 | 757 | 1,1831 | 942 | 475 | -9521 | 192 | 558 | 1,1481 | 421 | -2 |

| 2016 | -2,9741 | 831 | 895 | 1,0941 | 649 | 6641 | -973 | 253 | 6661 | 882 | 432 | -2121 |

| 2017 | -2,876 | 1,0291 | 656 | 1,024 | 839 | 6431 | -1,103 | 317 | 3881 | 1,013 | 5741 | -247 |

| 2018 | -3,098 | 1,2371 | 703 | 977 | 935 | 6661 | -1,164 | 4701 | 312 | 1,003 | 4811 | -200 |

| 2019 | -2,953 | 8051 | 675 | 1,062 | 6731 | 622 | -1,058 | 4361 | 417 | 989 | 5951 | -249 |

| 2020 | -2,7911 | 913 | -1,016 | -19,7011 | 3,168 | 5,082 | 6061 | 1,621 | 1,218 | 1,6221 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 19 | 212 | 235 | 3141 | 101 | 2361 | 60 | 126 | 2331 | 204 | 132 | 2021 |

| 2012 | 354 | 2621 | 240 | 82 | 100 | 731 | 152 | 1721 | 187 | 159 | 1561 | 239 |

| 2013 | 191 | 2781 | 139 | 191 | 2221 | 181 | 112 | 2421 | 187 | 225 | 2641 | 69 |

| 2014 | 1751 | 166 | 254 | 325 | 2181 | 326 | 232 | 1881 | 309 | 2521 | 291 | 268 |

| 2015 | 1911 | 271 | 71 | 2841 | 331 | 174 | 3021 | 125 | 155 | 3061 | 237 | 273 |

| 2016 | 671 | 192 | 292 | 2071 | 51 | 2551 | 383 | 151 | 2871 | 92 | 115 | 1901 |

| 2017 | 212 | 2001 | 132 | 236 | 161 | 2121 | 242 | 205 | 271 | 210 | 1691 | 152 |

| 2018 | 85 | 3891 | 220 | 183 | 288 | 2241 | 166 | 2261 | 84 | 176 | 521 | 203 |

| 2019 | 229 | -411 | 233 | 263 | 881 | 193 | 205 | 1881 | 184 | 147 | 1821 | 119 |

| 2020 | 2601 | 244 | -1,487 | -20,6791 | 2,833 | 4,846 | 1,7261 | 1,583 | 716 | 6801 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 19 | 212 | 235 | 3141 | 101 | 2361 | 60 | 126 | 2331 | 204 | 132 | 2021 |

| 2012 | 354 | 2621 | 240 | 82 | 100 | 731 | 152 | 1721 | 187 | 159 | 1561 | 239 |

| 2013 | 191 | 2781 | 139 | 191 | 2221 | 181 | 112 | 2421 | 187 | 225 | 2641 | 69 |

| 2014 | 1751 | 166 | 254 | 325 | 2181 | 326 | 232 | 1881 | 309 | 2521 | 291 | 268 |

| 2015 | 1911 | 271 | 71 | 2841 | 331 | 174 | 3021 | 125 | 155 | 3061 | 237 | 273 |

| 2016 | 1081 | 212 | 237 | 1971 | 41 | 2581 | 371 | 143 | 2891 | 118 | 130 | 2141 |

| 2017 | 197 | 1831 | 139 | 220 | 141 | 2111 | 228 | 190 | 421 | 249 | 1961 | 179 |

| 2018 | 81 | 3781 | 195 | 153 | 270 | 2141 | 149 | 2291 | 105 | 212 | 921 | 240 |

| 2019 | 237 | -501 | 168 | 219 | 631 | 175 | 193 | 1951 | 221 | 195 | 2341 | 161 |

| 2020 | 3151 | 289 | -1,683 | -20,6791 | 2,833 | 4,846 | 1,7261 | 1,583 | 716 | 6801 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 19 | 212 | 235 | 3141 | 101 | 2361 | 60 | 126 | 2331 | 204 | 132 | 2021 |

| 2012 | 354 | 2621 | 240 | 82 | 100 | 731 | 152 | 1721 | 187 | 159 | 1561 | 239 |

| 2013 | 191 | 2781 | 139 | 191 | 2221 | 181 | 112 | 2421 | 187 | 225 | 2641 | 69 |

| 2014 | 1751 | 166 | 254 | 325 | 2181 | 326 | 232 | 1881 | 309 | 2521 | 291 | 268 |

| 2015 | 1911 | 271 | 71 | 2841 | 331 | 174 | 3021 | 125 | 155 | 3061 | 237 | 273 |

| 2016 | 731 | 263 | 229 | 1871 | 42 | 2671 | 354 | 135 | 2691 | 145 | 151 | 2301 |

| 2017 | 185 | 1881 | 129 | 197 | 155 | 2161 | 215 | 184 | 181 | 267 | 2251 | 130 |

| 2018 | 121 | 4061 | 176 | 137 | 278 | 2191 | 136 | 2441 | 80 | 201 | 1341 | 182 |

| 2019 | 269 | 11 | 147 | 210 | 851 | 182 | 194 | 2071 | 208 | 185 | 2611 | 184 |

| 2020 | 2141 | 251 | -1,373 | -20,7871 | 2,725 | 4,781 | 1,7611 | 1,493 | 711 | 6541 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2 | 602 | 671 | 9031 | 583 | 2531 | -1,334 | 149 | 5131 | 719 | 203 | -3771 |

| 2012 | -2,960 | 6921 | 664 | 801 | 714 | 2641 | -1,361 | 2071 | 441 | 688 | 2331 | -314 |

| 2013 | -3,073 | 7601 | 660 | 814 | 6711 | 228 | -1,286 | 1951 | 421 | 697 | 2611 | -320 |

| 2014 | -2,9791 | 574 | 704 | 813 | 6941 | 261 | -1,311 | 1921 | 377 | 8021 | 174 | -272 |

| 2015 | -3,0061 | 560 | 686 | 8991 | 611 | 301 | -1,2541 | 67 | 403 | 8421 | 184 | -275 |

| 2016 | -3,0411 | 639 | 603 | 8871 | 598 | 4091 | -1,356 | 102 | 3791 | 790 | 317 | -4021 |

| 2017 | -3,088 | 8291 | 524 | 788 | 678 | 4311 | -1,345 | 112 | 3611 | 803 | 4051 | -399 |

| 2018 | -3,183 | 8481 | 483 | 794 | 647 | 4421 | -1,330 | 2441 | 228 | 827 | 4291 | -403 |

| 2019 | -3,182 | 8461 | 442 | 799 | 5851 | 429 | -1,263 | 2481 | 233 | 842 | 4131 | -368 |

| 2020 | -3,0511 | 669 | 471 | 9781 | 335 | 236 | -1,1201 | 38 | 502 | 9421 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2 | 602 | 671 | 9031 | 583 | 2531 | -1,334 | 149 | 5131 | 719 | 203 | -3771 |

| 2012 | -2,960 | 6921 | 664 | 801 | 714 | 2641 | -1,361 | 2071 | 441 | 688 | 2331 | -314 |

| 2013 | -3,073 | 7601 | 660 | 814 | 6711 | 228 | -1,286 | 1951 | 421 | 697 | 2611 | -320 |

| 2014 | -2,9791 | 574 | 704 | 813 | 6941 | 261 | -1,311 | 1921 | 377 | 8021 | 174 | -272 |

| 2015 | -3,0061 | 560 | 686 | 8991 | 611 | 301 | -1,2541 | 67 | 403 | 8421 | 184 | -275 |

| 2016 | -3,0821 | 619 | 658 | 8971 | 608 | 4061 | -1,344 | 110 | 3771 | 764 | 302 | -4261 |

| 2017 | -3,073 | 8461 | 517 | 804 | 698 | 4321 | -1,331 | 127 | 3461 | 764 | 3781 | -426 |

| 2018 | -3,179 | 8591 | 508 | 824 | 665 | 4521 | -1,313 | 2411 | 207 | 791 | 3891 | -440 |

| 2019 | -3,190 | 8551 | 507 | 843 | 6101 | 447 | -1,251 | 2411 | 196 | 794 | 3611 | -410 |

| 2020 | -3,1061 | 624 | 667 | 9781 | 335 | 236 | -1,1201 | 38 | 502 | 9421 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | -2,882 | 602 | 671 | 9031 | 583 | 2531 | -1,334 | 149 | 5131 | 719 | 203 | -3771 |

| 2012 | -2,960 | 6921 | 664 | 801 | 714 | 2641 | -1,361 | 2071 | 441 | 688 | 2331 | -314 |

| 2013 | -3,073 | 7601 | 660 | 814 | 6711 | 228 | -1,286 | 1951 | 421 | 697 | 2611 | -320 |

| 2014 | -2,9791 | 574 | 704 | 813 | 6941 | 261 | -1,311 | 1921 | 377 | 8021 | 174 | -272 |

| 2015 | -3,0061 | 560 | 686 | 8991 | 611 | 301 | -1,2541 | 67 | 403 | 8421 | 184 | -275 |

| 2016 | -3,0471 | 568 | 666 | 9071 | 607 | 3971 | -1,327 | 118 | 3971 | 737 | 281 | -4421 |

| 2017 | -3,061 | 8411 | 527 | 827 | 684 | 4271 | -1,318 | 133 | 3701 | 746 | 3491 | -377 |

| 2018 | -3,219 | 8311 | 527 | 840 | 657 | 4471 | -1,300 | 2261 | 232 | 802 | 3471 | -382 |

| 2019 | -3,222 | 8041 | 528 | 852 | 5881 | 440 | -1,252 | 2291 | 209 | 804 | 3341 | -433 |

| 2020 | -3,0051 | 662 | 357 | 1,0861 | 443 | 301 | -1,1551 | 128 | 507 | 9681 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 |

| 2012 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2013 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2014 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | -411 | -20 | 55 | 101 | 10 | -31 | 12 | 8 | -21 | -26 | -15 | -241 |

| 2017 | 15 | 171 | -7 | 16 | 20 | 11 | 14 | 15 | -151 | -39 | -271 | -27 |

| 2018 | 4 | 111 | 25 | 30 | 18 | 101 | 17 | -31 | -21 | -36 | -401 | -37 |

| 2019 | -8 | 91 | 65 | 44 | 251 | 18 | 12 | -71 | -37 | -48 | -521 | -42 |

| 2020 | -551 | -45 | 196 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 |

| 2012 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2013 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2014 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | -61 | -71 | 63 | 201 | 9 | -121 | 29 | 16 | 181 | -53 | -36 | -401 |

| 2017 | 27 | 121 | 3 | 39 | 6 | -41 | 27 | 21 | 91 | -57 | -561 | 22 |

| 2018 | -36 | -171 | 44 | 46 | 10 | 51 | 30 | -181 | 4 | -25 | -821 | 21 |

| 2019 | -40 | -421 | 86 | 53 | 31 | 11 | 11 | -191 | -24 | -38 | -791 | -65 |

| 2020 | 461 | -7 | -114 | 1081 | 108 | 65 | -351 | 90 | 5 | 261 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 |

| 2012 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2013 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2014 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 351 | -51 | 8 | 101 | -1 | -91 | 17 | 8 | 201 | -27 | -21 | -161 |

| 2017 | 12 | -51 | 10 | 23 | -14 | -51 | 13 | 6 | 241 | -18 | -291 | 49 |

| 2018 | -40 | -281 | 19 | 16 | -8 | -51 | 13 | -151 | 25 | 11 | -421 | 58 |

| 2019 | -32 | -511 | 21 | 9 | -221 | -7 | -1 | -121 | 13 | 10 | -271 | -23 |

| 2020 | 1011 | 38 | -310 | 1081 | 108 | 65 | -351 | 90 | 5 | 261 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

The appendix provides the components used to calculate the normal seasonal movement for total nonfarm employment for the following:

Tables B-5 through B-7 provide the normal seasonal movements calculated using the components from tables B-1 through B-4. The difference in the normal seasonal movement between the additive outliers only and all outlier types is provided in table B-8. The difference between the normal seasonal movement as previously published and the revised normal seasonal movement calculated with the additive outliers only and all outlier types is provided in tables B-9 and B-10, respectively. Some months are affected by the variable survey week adjustment, sometimes referred to as the 4- versus 5-week effect.8

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | -2,606 | 9541 | 904 | 883 | 814 | 3371 | -1,209 | 3791 | 628 | 847 | 3891 | -75 |

| 2013 | -2,882 | 1,0381 | 799 | 1,005 | 8931 | 409 | -1,174 | 4371 | 608 | 922 | 5251 | -251 |

| 2014 | -2,8041 | 740 | 958 | 1,138 | 9121 | 587 | -1,079 | 3801 | 686 | 1,0541 | 465 | -4 |

| 2015 | -2,8151 | 831 | 757 | 11831 | 942 | 475 | -9521 | 192 | 558 | 1,1481 | 421 | -2 |

| 2016 | -2,9741 | 831 | 895 | 1,0941 | 649 | 6641 | -973 | 253 | 6661 | 882 | 432 | -2121 |

| 2017 | -2,876 | 1,0291 | 656 | 1,024 | 839 | 6431 | -1,103 | 317 | 3881 | 1,013 | 5741 | -247 |

| 2018 | -3,098 | 1,2371 | 703 | 977 | 935 | 6661 | -1,164 | 4701 | 312 | 1,003 | 4811 | -200 |

| 2019 | -2,953 | 8051 | 675 | 1,062 | 6731 | 622 | -1,058 | 4361 | 417 | 989 | 5951 | -249 |

| 2020 | -2,7911 | 913 | -1,016 | -19,6991 | 3,169 | 5,085 | 5981 | 1,622 | 1,231 | 1,6071 | 550 | -510 |

| 2021 | -2,6311 | 1,155 | 1,179 | 1,0501 | 946 | 1,189 | -411 | 495 | 7041 | 1,659 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 354 | 2621 | 240 | 82 | 100 | 731 | 152 | 1721 | 187 | 159 | 1561 | 239 |

| 2013 | 191 | 2781 | 139 | 191 | 2221 | 181 | 112 | 2421 | 187 | 225 | 2641 | 69 |

| 2014 | 1751 | 166 | 254 | 325 | 2181 | 326 | 232 | 1881 | 309 | 2521 | 291 | 268 |

| 2015 | 1911 | 271 | 71 | 2841 | 331 | 174 | 3021 | 125 | 155 | 3061 | 237 | 273 |

| 2016 | 1081 | 212 | 237 | 1971 | 41 | 2581 | 371 | 143 | 2891 | 118 | 130 | 2141 |

| 2017 | 76 | 1861 | 150 | 320 | 474 | 2161 | 139 | 104 | 301 | 3 | 911 | 63 |

| 2018 | 84 | 4311 | 315 | 408 | 694 | 2321 | -21 | 1071 | -117 | -31 | -791 | 115 |

| 2019 | 213 | 821 | 377 | 639 | 2831 | 378 | 50 | 141 | -103 | -163 | -31 | 89 |

| 2020 | 1541 | 336 | -1,119 | -19,0901 | 2,322 | 4,500 | 1,3691 | 1,436 | 564 | 3011 | 77 | -177 |

| 2021 | 3431 | 643 | 1,059 | 1,7191 | 219 | 577 | 6331 | 256 | 1091 | 290 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 354 | 2621 | 240 | 82 | 100 | 731 | 152 | 1721 | 187 | 159 | 1561 | 239 |

| 2013 | 191 | 2781 | 139 | 191 | 2221 | 181 | 112 | 2421 | 187 | 225 | 2641 | 69 |

| 2014 | 1751 | 166 | 254 | 325 | 2181 | 326 | 232 | 1881 | 309 | 2521 | 291 | 268 |

| 2015 | 1911 | 271 | 71 | 2841 | 331 | 174 | 3021 | 125 | 155 | 3061 | 237 | 273 |

| 2016 | 1081 | 212 | 237 | 1971 | 41 | 2581 | 371 | 143 | 2891 | 118 | 130 | 2141 |

| 2017 | 213 | 1901 | 142 | 205 | 223 | 1971 | 183 | 145 | 991 | 141 | 2001 | 176 |

| 2018 | 133 | 4021 | 225 | 179 | 333 | 1831 | 66 | 2191 | 57 | 145 | 1021 | 248 |

| 2019 | 279 | 241 | 224 | 288 | 771 | 130 | 78 | 1601 | 163 | 93 | 2521 | 200 |

| 2020 | 3391 | 376 | -1,498 | -20,4931 | 2,642 | 4,505 | 1,3881 | 1,665 | 919 | 6471 | 333 | -115 |

| 2021 | 5201 | 710 | 704 | 2631 | 447 | 557 | 6891 | 517 | 4241 | 677 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 354 | 2621 | 240 | 82 | 100 | 731 | 152 | 1721 | 187 | 159 | 1561 | 239 |

| 2013 | 191 | 2781 | 139 | 191 | 2221 | 181 | 112 | 2421 | 187 | 225 | 2641 | 69 |

| 2014 | 1751 | 166 | 254 | 325 | 2181 | 326 | 232 | 1881 | 309 | 2521 | 291 | 268 |

| 2015 | 1911 | 271 | 71 | 2841 | 331 | 174 | 3021 | 125 | 155 | 3061 | 237 | 273 |

| 2016 | 1081 | 212 | 237 | 1971 | 41 | 2581 | 371 | 143 | 2891 | 118 | 130 | 2141 |

| 2017 | 197 | 1831 | 139 | 220 | 141 | 2111 | 228 | 190 | 421 | 249 | 1961 | 179 |

| 2018 | 81 | 3781 | 195 | 153 | 270 | 2141 | 149 | 2291 | 105 | 212 | 921 | 240 |

| 2019 | 237 | -501 | 168 | 219 | 631 | 175 | 193 | 1951 | 221 | 195 | 2341 | 161 |

| 2020 | 3151 | 289 | -1,683 | -20,6791 | 2,833 | 4,846 | 1,7261 | 1,583 | 716 | 6801 | 264 | -306 |

| 2021 | 2331 | 536 | 785 | 2691 | 614 | 962 | 1,0911 | 483 | 3791 | 648 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2 | 6921 | 664 | 801 | 714 | 2641 | -1,361 | 2071 | 441 | 688 | 2331 | -314 |

| 2013 | -3,073 | 7601 | 660 | 814 | 6711 | 228 | -1,286 | 1951 | 421 | 697 | 2611 | -320 |

| 2014 | -2,9791 | 574 | 704 | 813 | 6941 | 261 | -1,311 | 1921 | 377 | 8021 | 174 | -272 |

| 2015 | -3,0061 | 560 | 686 | 8991 | 611 | 301 | -1,2541 | 67 | 403 | 8421 | 184 | -275 |

| 2016 | -3,0821 | 619 | 658 | 8971 | 608 | 4061 | -1,344 | 110 | 3771 | 764 | 302 | -4261 |

| 2017 | -2,952 | 8431 | 506 | 704 | 365 | 4271 | -1,242 | 213 | 3581 | 1,010 | 4831 | -310 |

| 2018 | -3,182 | 8061 | 388 | 569 | 241 | 4341 | -1,143 | 3631 | 429 | 1,034 | 5601 | -315 |

| 2019 | -3,166 | 7231 | 298 | 423 | 3901 | 244 | -1,108 | 4221 | 520 | 1,152 | 5981 | -338 |

| 2020 | -2,9451 | 577 | 103 | -6091 | 847 | 585 | -7711 | 186 | 667 | 1,3061 | 473 | -333 |

| 2021 | -2,9741 | 512 | 120 | -6691 | 727 | 612 | -6741 | 239 | 5951 | 1,369 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2 | 6921 | 664 | 801 | 714 | 2641 | -1,361 | 2071 | 441 | 688 | 2331 | -314 |

| 2013 | -3,073 | 7601 | 660 | 814 | 6711 | 228 | -1,286 | 1951 | 421 | 697 | 2611 | -320 |

| 2014 | -2,9791 | 574 | 704 | 813 | 6941 | 261 | -1,311 | 1921 | 377 | 8021 | 174 | -272 |

| 2015 | -3,0061 | 560 | 686 | 8991 | 611 | 301 | -1,2541 | 67 | 403 | 8421 | 184 | -275 |

| 2016 | -3,0821 | 619 | 658 | 8971 | 608 | 4061 | -1,344 | 110 | 3771 | 764 | 302 | -4261 |

| 2017 | -3,089 | 8391 | 514 | 819 | 616 | 4461 | -1,286 | 172 | 2891 | 872 | 3741 | -423 |

| 2018 | -3,231 | 8351 | 478 | 798 | 602 | 4831 | -1,230 | 2511 | 255 | 858 | 3791 | -448 |

| 2019 | -3,232 | 7811 | 451 | 774 | 5961 | 492 | -1,136 | 2761 | 254 | 896 | 3431 | -449 |

| 2020 | -3,1301 | 537 | 482 | 7941 | 527 | 580 | -7901 | -43 | 312 | 9601 | 217 | -395 |

| 2021 | -3,1511 | 445 | 475 | 7871 | 499 | 632 | -7301 | -22 | 2801 | 982 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | -2,960 | 6921 | 664 | 801 | 714 | 2641 | -1,361 | 2071 | 441 | 688 | 2331 | -314 |

| 2013 | -3,073 | 7601 | 660 | 814 | 6711 | 228 | -1,286 | 1951 | 421 | 697 | 2611 | -320 |

| 2014 | -2,9791 | 574 | 704 | 813 | 6941 | 261 | -1,311 | 1921 | 377 | 8021 | 174 | -272 |

| 2015 | -3,0061 | 560 | 686 | 8991 | 611 | 301 | -1,2541 | 67 | 403 | 8421 | 184 | -275 |

| 2016 | -3,0821 | 619 | 658 | 8971 | 608 | 4061 | -1,344 | 110 | 3771 | 764 | 302 | -4261 |

| 2017 | -3,073 | 8461 | 517 | 804 | 698 | 4321 | -1,331 | 127 | 3461 | 764 | 3781 | -426 |

| 2018 | -3,179 | 8591 | 508 | 824 | 665 | 4521 | -1,313 | 2411 | 207 | 791 | 3891 | -440 |

| 2019 | -3,190 | 8551 | 507 | 843 | 6101 | 447 | -1,251 | 2411 | 196 | 794 | 3611 | -410 |

| 2020 | -3,1061 | 624 | 667 | 9801 | 336 | 239 | -1,1281 | 39 | 515 | 9271 | 286 | -204 |

| 2021 | -2,8641 | 619 | 394 | 7811 | 332 | 227 | -1,1321 | 12 | 3251 | 1,011 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2013 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2014 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 |

| 2017 | -137 | -41 | 8 | 115 | 251 | 191 | -44 | -41 | -691 | -138 | -1091 | -113 |

| 2018 | -49 | 291 | 90 | 229 | 361 | 491 | -87 | -1121 | -174 | -176 | -1811 | -133 |

| 2019 | -66 | 581 | 153 | 351 | 2061 | 248 | -28 | -1461 | -266 | -256 | -2551 | -111 |

| 2020 | -1851 | -40 | 379 | 1,4031 | -320 | -5 | -191 | -229 | -355 | -3461 | -256 | -62 |

| 2021 | -1771 | -67 | 355 | 1,4561 | -228 | 20 | -561 | -261 | -3151 | -387 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2013 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2014 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 |

| 2017 | -121 | 31 | 11 | 100 | 333 | 51 | -89 | -86 | -121 | -246 | -1051 | -116 |

| 2018 | 3 | 531 | 120 | 255 | 424 | 181 | -170 | -1221 | -222 | -243 | -1711 | -125 |

| 2019 | -24 | 1321 | 209 | 420 | 2201 | 203 | -143 | -1811 | -324 | -358 | -2371 | -72 |

| 2020 | -1611 | 47 | 564 | 1,5891 | -511 | -346 | -3571 | -147 | -152 | -3791 | -187 | 129 |

| 2021 | 1101 | 107 | 274 | 1,4501 | -395 | -385 | -4581 | -227 | -2701 | -358 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2013 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 |

| 2014 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 | 0 | 0 | 01 |

| 2017 | 16 | 71 | 3 | -15 | 82 | -141 | -45 | -45 | 571 | -108 | 41 | -3 |

| 2018 | 52 | 241 | 30 | 26 | 63 | -311 | -83 | -101 | -48 | -67 | 101 | 8 |

| 2019 | 42 | 741 | 56 | 69 | 141 | -45 | -115 | -351 | -58 | -102 | 181 | 39 |

| 2020 | 241 | 87 | 185 | 1861 | -191 | -341 | -3381 | 82 | 203 | -331 | 69 | 191 |

| 2021 | 2871 | 174 | -81 | -61 | -167 | -405 | -4021 | 34 | 451 | 29 | 2 | 2 |

| Note: 1 These values come from a 5-week survey interval. 2 Not applicable at time of annual review. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||||

Nicole Hudson, Jeannine Mercurio, and Jurgen Kropf, "The challenges of seasonal adjustment for the Current Employment Statistics survey during the COVID-19 pandemic," Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2022, https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2022.14

1 For an example of one such publication, see “The challenges of seasonal adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic” Commissioner’s Corner (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 21, 2020), https://www.bls.gov/blog/2020/the-challenges-of-seasonal-adjustment-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.htm.

2 For more information on seasonal adjustment, see “Technical notes for the Current Employment Statistics survey: seasonal adjustment" Current Employment Statistics—CES (national) (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 4, 2022), https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cestn.htm#section6e.

3 All CES series are evaluated annually for sample size, coverage, and response rates. Reconstruction of time series may result from a reevaluation of the sample and universe coverage for CES industries. In this case, seasonal adjustment is rerun for the entire history of the reconstructed time series.

4 X-13 ARIMA-SEATS is publicly available from the U.S. Census Bureau at https://www.census.gov/data/software/x13as.html.

5 Brian C. Monsell, "Time series responses to the COVID-19 pandemic at BLS for monthly and weekly series," Statistical Survey Paper (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 2021), https://www.bls.gov/osmr/research-papers/2021/pdf/st210040.pdf.

6 Rebecca Bevans, “An introduction to the Akaike information criterion,” Scribbr, March 26, 2020, https://www.scribbr.com/statistics/akaike-information-criterion/.

7 See “Technical notes for the Current Employment Statistics survey: seasonal adjustment" Current Employment Statistics—CES (national) (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 4, 2022), https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cestn.htm#section6e.

8 See “Technical notes for the Current Employment Statistics survey: seasonal adjustment" Current Employment Statistics—CES (national) (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 4, 2022), https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cestn.htm#section6e.