An official website of the United States government

United States Department of Labor

United States Department of Labor

The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 called for a wider statistical net to gather work injury and illness data and to measure their numbers and incidence rates. The current mandatory Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII), modified on several occasions to incorporate various changes discussed in later sections, still meets the basic requirements of the 1970 act for counts and rates covering a broad spectrum of work injuries and illnesses in various work settings. In response to a 1987 National Academy of Sciences (NAS) study (described in more detail in the History section), SOII began to collect information on the circumstances of nonfatal cases involving days away from work and the characteristics of workers sustaining such injuries and illnesses for the 1992 calendar year. SOII is a federal-state cooperative program in which employers’ reports are collected and processed by state agencies in cooperation with the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

SOII estimates the number and frequency (incidence rates) of workplace injuries and illnesses based on recordkeeping logs kept by employers during the year. These records reflect not only the year’s injury and illness experience but also the employer’s understanding of which cases are work-related under recordkeeping guidelines promulgated by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Although SOII uses OSHA’s recordkeeping guidelines to facilitate convenient collection of data, it is not administered by OSHA. In addition, the scope of SOII encompasses industries not regulated by OSHA, such as railroad and mining. Information collected through the program is used for purely statistical purposes, will not be viewed by OSHA, and cannot be used for any regulatory purpose.

Besides injury and illness counts, survey respondents also are asked to provide additional information for the following two subsets of nonfatal cases:

Employers answer several questions about these cases, including the demographics of the worker, the nature of the disabling condition, the event and source producing that condition, and the part of body affected.

The following definitions of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses used in SOII are the same as those established in the recordkeeping guidelines of OSHA. These are also used by employers to keep logs and case details of such incidents throughout the survey (calendar) year. (See the More info section for citations of instructional materials useful in understanding the types of cases recorded under current recordkeeping guidelines.)

Nonfatal recordable workplace injuries and illnesses are those that result in any one or more of the following:

In addition to these four criteria, employers must also record any significant work-related injuries or illnesses that are diagnosed by a physician or other licensed healthcare professional or other instances that meet additional criteria discussed below. Significant work-related injuries or illnesses include cancers, chronic irreversible diseases, fractured or cracked bones (including teeth), or punctured eardrums. Additional cases that must be recorded as workplace injuries or illnesses include the following:

Additional details regarding recordability of nonfatal work-related injuries and illnesses can be found in Detailed guidance for OSHA’s injury and illness recordkeeping rule.

The distinction between an occupational injury and occupational illness was eliminated from OSHA recordkeeping guidelines when revisions were implemented in 2002. The OSHA guidelines now define an injury or illness as an abnormal condition or disorder. For purposes of clarification for SOII, these terms are still defined separately. Nature codes from the Occupational Injury and Illness Classification System (OIICS) manual are used to code distinct injury and illness cases.

There are five case type categories (skin disorder, respiratory condition, poisoning, hearing loss, and all other illnesses) of occupational illnesses and disorders that are used to classify recordable illnesses, described as follows. Examples of each category are provided, but these are not a complete listing of the types of illnesses and disorders that are counted under each category. (See the OIICS manual for a more comprehensive list of injuries and illnesses and their associated codes.)

Nonfatal injury and illness estimates are tabulated from SOII data for several types of cases, including the following:

Days away from work, job restriction, or transfer (DART) cases are those which involve days away from work beyond the day of injury or onset of illness, days of job transfer or restricted work activity, or both. DART is comprised of the two case types listed below.

Other recordable cases are those which are recordable injuries or illnesses under OSHA recordkeeping guidelines but do not result in any days away from work, nor a job transfer or restriction, beyond the day of the injury or onset of illness. For example, a worker cuts their finger on machinery during their Wednesday afternoon work shift. The injury required medical attention, for which the employee received sutures at the local emergency room. They were able to return to their normally scheduled workday on the following day (Thursday) and performed their typical work duties without any restrictions.

SOII covers private, state government, and local government wage and salary workers, while the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) also covers workers on small farms, the self-employed, family workers, and federal government workers.

Because of these scope coverage differences (outlined in exhibit 1) CFOI and SOII data are not directly comparable.

| Characteristic | Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) | Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII) |

|---|---|---|

|

Collection method |

Uses multiple source documents (e.g., death certificates, workers’ compensation reports, and media reports) to substantiate each case, ensuring a census. | Uses a sample of approximately 230,000 establishments to generate detailed estimates. Mandatory survey from BLS for private sector establishments.1 |

|

Publication Frequency |

Annually | Annual summary estimates are released annually. Case and demographic estimates are released biennially. |

|

Geographic scope |

Data are collected from each state, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Guam. | Data are collected from participating states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Guam.2 |

|

Private sector workers |

Included | Included |

|

Government workers |

Includes federal, state, local, foreign, and other government workers | Includes state and local workers since 2008 uniformly across the nation3 |

|

Self-employed |

Included | Not included4 |

|

Volunteer workers |

Included5 | Varies6 |

|

Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting |

Included | Agriculture establishments (NAICS 111 and 112) with more than 10 employees7 |

|

Mining |

Included | Included8 |

|

Railroad |

Included | Included9 |

|

Treatment of temporary workers |

Coded to the industry in which they are directly employed10 | Coded to the industry in which they are directly employed |

|

Specific industries |

All included | Private households, postal workers (NAICS 491), space research and technology (NAICS 927), and national security and international affairs (NAICS 928) not included11 |

|

Illnesses |

Not included | Included |

|

Age of workers included |

All | All |

|

Cases that occur in territorial waters |

Included | Included12 |

|

1 Government establishments are not necessarily required by law to respond. “For state and local government employers, your state laws determine whether participation in the survey [SOII] is mandatory.” https://www.bls.gov/respondents/iif/faqs.htm. 2 Data for nonparticipating states are collected and used solely for the tabulation of national estimates. 3 SOII does not cover workers regulated by other federal agencies, 29 U.S.C. § 653(b)(1) (2011). For example, mines regulated by the Mine Safety and Health Administration or rail transportation firms regulated by the Federal Railroad Administration, nor does it cover federal workers per 29 U.S.C. § 652(5) (2011). 4 Self-employed workers are not covered by the Occupational Safety Act of 1970. https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=12775. 5 See Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI): Definitions, https://www.bls.gov/iif/definitions/occupational-safety-and-health-definitions.htm and Matthew M. Gunter, “Fatal Occupational Injuries to Volunteer Workers, 2003–07,” Monthly Labor Review, (December 2010), https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/cwc/fatal-occupational-injuries-to-volunteer-workers-200307.pdf. 6 Different state OSHA plans may cover volunteers. For more information on if a state covers volunteers, please contact the respective state OSHA office. National OSHA regulations do not cover volunteer workers; please see 29 C.F.R. § 1904(31)(a) (2013). See also https://webapps.dol.gov/elaws/osharecordkeeping.htm. 7 The “small agriculture” exclusion is due to a recurring appropriations rider for OSHA that exempts agricultural operations employing 10 or fewer employees from the 1970 OSH Act in its entirety, including mandatory response to the BLS annual survey (Pollack and Gellerman Keimig, 1987: 19). See for example, OSHA Directive CPL-02-00-051. 8 Mining data are collected by the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) and are provided to SOII for inclusion in the estimates. 9 Railroad data are collected by the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) and are provided to SOII for inclusion in the estimates. 10 Starting in 2011, CFOI began collecting information on contractors. Now temporary workers are coded to their directly employed industry as in the past but also the industry to which they were fatally injured in as well (contractor industry). For more information on contractor data in CFOI, see: https://www.bls.gov/iif/definitions/occupational-safety-and-health-definitions.htm. 11 Though technically no longer excluded from coverage under the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 due to amended language in the 1998 Postal Employees Safety Enhancement Act, BLS has not yet modified SOII to include the U.S. Postal Service. 12 Cases that occur in territorial waters within 3 nautical miles from the general coastline or 9 nautical miles (3 leagues) from Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico are included. For additional rules including if the vessel is attached to the seabed, see https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=INTERPRETATIONS&p_id=29408. |

||

BLS publishes statistics on nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses from SOII and fatal workplace injuries from CFOI. Most of these data can be located at the Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities (IIF) program homepage. SOII and CFOI share several systems to classify industry, occupation, case circumstances, and worker characteristics. Changes among these systems over the past several years have affected SOII (both estimates by industry and by case circumstances and worker characteristics) and CFOI outputs, as described below. More information on these classifications and how they have affected the data series can be found in the online notices, the Presentation section, and the History section.

BLS has long relied on state, regional, and national staff to manually assign Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) and Occupational Injury and Illness Classification System (OIICS) codes. However, in recent years, their role in SOII coding has begun to shift. Motivated both by a desire to improve coding quality as well as evidence that new automated techniques might result in classification accuracies similar to those achieved by staff, BLS began using computers to automatically assign SOC codes to a portion of SOII cases starting with reference year 2014 data.1 For reference year 2015, BLS expanded autocoding further to include some OIICS coding as well. BLS state and regional staff remain responsible for assigning many codes and are instructed to review and validate all automatically assigned codes.

BLS developed OIICS to provide a consistent set of classifications of the circumstances of the characteristics associated with workplace injuries, illnesses, and fatalities. OIICS is used to classify the circumstances of each injury, illness, and fatality case. BLS developed the original OIICS structure with input from data users and states participating in the BLS Occupational Safety and Health Statistics (OSHS) federal-state cooperative programs. The original system was released in December 1992 and approved for use as the American National Standard for Information Management for Occupational Safety and Health in 1995 (ANSI Z16.2—1995). In September 2007, BLS updated OIICS classifications to incorporate various interpretations and corrections.

The OIICS revision in September 2010 was the first major revision since this classification system was first developed in 1992. BLS implemented a revised OIICS structure based on input from many stakeholders. In February 2008, BLS issued a Federal Register Notice requesting suggestions for proposed changes to OIICS. In addition, BLS sent out numerous letters and emails to stakeholders who use the OIICS to classify injury and illness data. In April 2010, BLS issued a draft of the revised OIICS 2.01 manual to interested parties, requesting their comments. The team evaluated the comments received, made revisions, and issued the completed OIICS 2.01 manual in September 2010. Due to substantial differences between OIICS 2.01 and the original OIICS structure (which was used from 1992 to 2010), BLS advises against making comparisons of the case characteristics from 2011 forward to prior years. More on OIICS can be found here: https://www.bls.gov/iif/definitions/occupational-injuries-and-illnesses-classification-manual.htm.

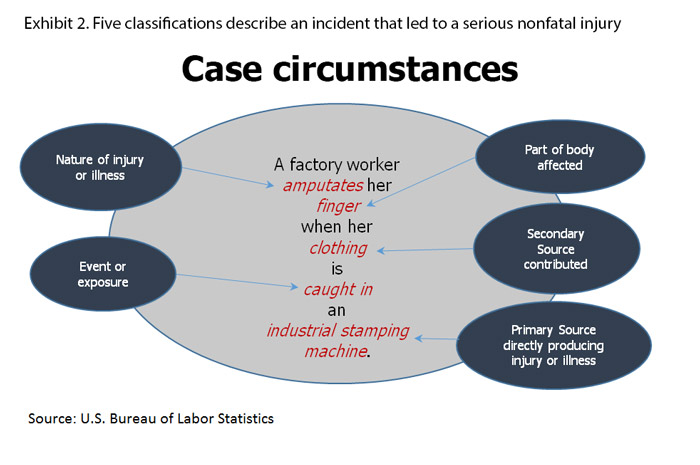

SOII and CFOI use five classifications to describe each incident that led to a serious nonfatal injury or illness or a fatal injury:

Exhibit 2 is an illustrative example of how SOII may use OIICS codes to describe the case circumstances of an injury or illness incident:

From 1992 to 2002, SOII and CFOI used the 1987 Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) system to define industry. Despite periodic updates to the SIC system, increasing criticism led to the development of a new, more comprehensive system that reflects more recent and rapid economic changes. Many industrial changes were not accounted for under the SIC system, such as recent developments in information services, new forms of health care provision, expansion of the services sector, and high-tech manufacturing.

The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) was adopted to define industry beginning with the 2003 reference year. Because of the substantial differences between NAICS and the SIC system, the results by industry in 2003 constitute a break in series. NAICS 2017 was adopted to define industry starting with the 2019 reference year. NAICS 2012 was used to define industry for reference years 2014–18; NAICS 2007 was used to define industry for reference years 2009–13; and NAICS 2002 was used to define industry for reference years 2003–08. Comparisons of estimates using NAICS 2017 to previous years under prior NAICS coding structures should be made with caution. Users are advised not to make comparisons between industry data for 2003 forward and the industry data for previous years. Note that the change from NAICS 2007 to NAICS 2012 resulted in a break in series among industry-level estimates from SOII; however, no series break resulted for the CFOI data. More details on the current NAICS classification as it is used in the IIF programs are below. You can also find a timeline with the details of which coding structures are used for which year in the History section.

NAICS was developed in cooperation with Canada and Mexico to replace the SIC system, and it was one of the most profound changes for statistical programs focused on measuring economic activities. NAICS uses a process-oriented conceptual framework to group establishments into industries according to the activity in which they are primarily engaged. Establishments using similar raw material inputs, similar capital equipment, and similar labor are classified in the same industry. In other words, establishments that do similar things in similar ways are classified together.

NAICS provides the means to ensure that SOII and CFOI statistics accurately reflect changes in a dynamic U.S. economy. The downside of this change is that these improved statistics resulted in time series breaks due to the significant differences between SIC and NAICS. Every sector of the economy was restructured and redefined under NAICS that recognized the information-based economy—a new information sector that combined communications, publishing, motion picture and sound recording, and online services. NAICS restructured the manufacturing sector to recognize new high-tech industries. A new subsector was devoted to computers and electronics, including reproduction of software. Retail trade was redefined. In addition, eating and drinking places were transferred to a new accommodation and food services sector. The difference between the retail trade and wholesale trade sectors is now based on how each store conducts business. For example, many computer stores were reclassified from wholesale to retail. Nine new service sectors and 250 new service-providing industries were recognized with the adoption of NAICS in 2003.

NAICS uses a 6-digit hierarchical coding system to classify economic activities into 20 industry sectors; 4 sectors are mainly goods-producing sectors, and 16 are entirely service-providing sectors. The 6-digit hierarchical structure of NAICS 2017 allowed for the identification of 1,057 industries. NAICS is revised on a 5-year cycle to reflect changes in the economy, resulting in new standards for 2007, 2012 and 2017. These changes were incorporated into SOII and CFOI industry data 2 years later, for 2009, 2014 and 2019 respectively. These changes resulted in a series break for SOII industry data from 2013 to 2014, and footnotes should be consulted to check for incompatibility in other cases. For additional information regarding differences between NAICS 2002, NAICS 2007, NAICS 2012, and NAICS 2017, visit the U.S. Census Bureau NAICS webpage. See the Presentation section for more information on the series.

The following list identifies the individual goods-producing and service-providing industry sectors according to NAICS 2017 classifications.

Goods-producing NAICS industry sectors:

Service-providing NAICS industry sectors:

In addition to these NAICS sectors, SOII and CFOI statistics are tabulated for several additional NAICS aggregations that are unique to BLS, including the following:

BLS also has a unique special trade contractors (NAICS 238) that have both residential and nonresidential elements.

BLS will attempt to provide further industry detail in NAICS by adding 19 industries in subsector 238, specialty trade contractors. These additional industries will provide data, where available, about residential and nonresidential contractors. Some of the new industries will include residential and nonresidential roofing contractors, and residential and nonresidential electrical contractors.2

The 19 industries are:

From 1992 to 2002, the program used the U.S. Census Bureau occupational classification system. Beginning with the 2003 reference year, SOII and CFOI began using the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system to define occupations. Due to the substantial differences between the SOC and Census system, the results by occupation for 2003 constitute a break in series. Users are advised against making comparisons between occupation data for 2003 forward and the occupation data for previous years. More information on Census’ occupational classification system can be found on the Census website. More information on SOC can be found on the SOC homepage. Please note that SOII and CFOI used the 2000 SOC to classify occupation data for years 2003–10, the 2010 SOC for years 2011–18, and the 2018 SOC for 2019 forward. More details on the current SOC classification as it is used in the IIF programs is below.

Beginning with the 2019 reference year, CFOI and SOII began using the 2018 SOC system for coding occupations. The SOC 2010 system was used for reference years 2011 through 2018. The SOC 2000 system was used for reference years 2003 through 2010. Comparisons of estimates using SOC 2018 to previous years under prior SOC coding structures should be made with caution.

The 2018 SOC system classifies workers at four levels of aggregation:

For the SOC 2018 system, all occupations are clustered into one of 23 major groups, within which are 98 minor groups, 459 broad occupations, and 867 detailed occupations. Occupations with similar skills or work activities are grouped at each of the four levels of hierarchy to facilitate comparisons. For example, life, physical, and social science occupations (19-0000) is divided into five minor groups: life scientists (19-1000); physical scientists (19-2000); social scientists and related workers (19-3000); life, physical, and social science technicians (19-4000); and occupational health and safety specialists and technicians (19-5000). Life scientists contains broad occupations such as agricultural and food scientists (19-1010) and biological scientists (19-1020). The broad occupation biological scientists include detailed occupations such as biochemists and biophysicists (19-1021) and microbiologists (19-1022).

Each item in the hierarchy is designated by a 6-digit code. The first 2 digits of the SOC code represent the major group; the 3rd digit represents the minor group; the 4th and 5th digits represent the broad occupation; and the detailed occupation is represented by the 6th digit. Major group codes end with 0000 (e.g., 33-0000, protective service occupations), minor groups end with 000 (e.g., 33-2000, firefighting and prevention workers), and broad occupations end with 0 (e.g., 33-2020, fire inspectors). (The zeros are not always printed.) All residuals ("other," "miscellaneous," or "all other"), whether at the detailed or broad occupation or minor group level, contain a 9 at the level of the residual. Detailed residual occupations end in 9 (e.g., 33-9099, protective service workers, all other); broad occupations that are minor group residuals end in 90 (e.g., 33-9090, miscellaneous protective service workers); and minor groups that are major group residuals end in 9000 (e.g., 33-9000, other protective service workers):

33-0000 protective service occupations

33-9000 other protective service workers

33-9090 miscellaneous protective service workers

33-9099 protective service workers, all other

Both the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) as well as the component of the Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII) capturing case circumstances and worker characteristics were implemented in 1992, following recommendations of a National Academies of Science review highlighting the need to capture detailed case circumstances and worker characteristics for fatal and nonfatal workplace incidents, respectively. At their inception, each of these series used separate methods to categorize the race or ethnicity of injured or ill workers. For example, SOII categorized Hispanic workers separately, while CFOI categorized Hispanic workers by race (e.g., Black or White) and also provided a total count of Hispanic workers. The remaining race and ethnicity categories for both series were:

The classification of workers by race and ethnicity for CFOI and SOII is based on the 1997 Standards for Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity as defined by the Office of Management and Budget.

In 1999, CFOI amended race categories so that Hispanic workers no longer counted as a race but solely as an ethnicity. Three additional changes were also incorporated to race and ethnicity categories:

In 2002, SOII incorporated these same race categories. One result of this revision is that individuals may be categorized in more than one race or ethnic group. Race and ethnicity is one of the few data elements that are optional in SOII. This resulted in 40 percent of the cases involving days away from work for which race and ethnicity were not reported in the 2016 SOII.

1 See Automated Coding of Worker Injury Narratives, https://www.bls.gov/osmr/research-papers/2014/pdf/st140040.pdf.

2 An excerpt from James A. Walker and John B. Murphy, “Implementing the North American Industry Classification System at BLS,” Monthly Labor Review (December 2001), p. 18, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2001/12/art2full.pdf.