An official website of the United States government

United States Department of Labor

United States Department of Labor

This article examines three patterns of output growth—productivity-driven, hours-driven, and balanced growth in productivity and hours worked—in a sample of fast-growing industries. While growth in annual hours worked has slowed at the national level since 2000, many industries have sustained high rates of output growth through rapid gains in productivity. Less often, some industries have expanded by accelerating or maintaining growth in hours worked. Major developments in technologies and business practices are common themes in industries with high productivity growth rates. This article provides an industry-based framework for understanding aggregate output growth in an era of relative labor scarcity.

Where does economic growth come from? Major areas of economic research are devoted to studying how to increase it. Economic growth makes it easier to balance the national budget and gives prestige to a nation. It can also improve the average person’s standard of living.1

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics measures labor productivity as the ratio of output per hour of work.2 Thus, one way to look at output growth is to break it down into two components:

Without growth in either hours worked or productivity, there is economic stagnation.3 As chart 1 demonstrates, the growth rate of output can be approximated as the sum of the growth rates of these two components. (For more information, see Appendix: Derivation of the output growth formula.)

| Period | Output | Hours worked | Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–2000 | 4.0 | 1.7 | 2.2 |

| 2000–07 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 2.6 |

| 2007–19 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| 2019–24 | 2.6 | 0.5 | 2.1 |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |||

The end dates for the periods on the chart align with business cycles.4 (Data are reported for the nonfarm business sector.5) Overall, the chart displays a decelerating trend in the annual percent changes for output from 1990 to 2019, with a moderate resurgence, so far, after 2019.6

Productivity grew faster than hours worked in all periods. Hours growth flattened during the 2000–07 “jobless recovery,” after the “dot-com bust” recession. Productivity growth was responsible for nearly all output growth during this period. Finally, a weak but stable growth trend for hours worked appeared in the two periods from 2007–24. In the 2007–19 period, productivity grew roughly two and a half times as fast as hours worked. In the 2019–24 period, productivity then grew more than four times as fast as hours worked. However, productivity growth in the last two business cycles—so far—has remained a little slower than in the 1990–2007 periods.

The big picture tells only part of the story. Businesses throughout the U.S. economy produce goods and services through a variety of processes, using different combinations of labor, equipment, materials, and technologies. As a result, they will react differently to economic shocks. For example, consider how various workplaces reacted to the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some types of workplaces remained fully or mostly staffed; some shut down. Some businesses were able to produce goods and services despite reduced workforces; some struggled.

Similarly, during economic booms, not all types of businesses grow in the same way—or at all. To understand the statistics for the U.S. economy, it is useful to analyze trends in the underlying industries. Different industries have different stories to tell.

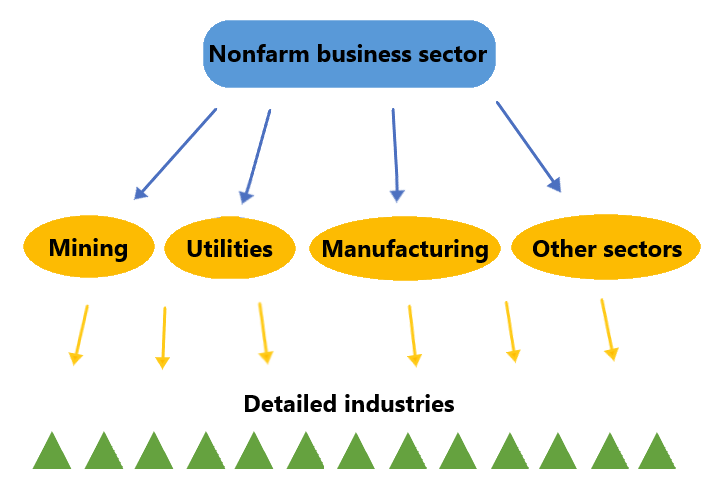

The BLS Office of Productivity and Technology (OPT) publishes labor productivity measures for hundreds of U.S. industries.7 The North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) is used throughout U.S. statistics to classify businesses into industries. NAICS further groups these industries into sectors. Figure 1 conveys the sector-industry hierarchy.

Figure. 1. Hierarchy of industries and sectors in the economy

Chart 2 presents annual growth in output, hours worked, and productivity for seven sectors, across four business cycles, from 1990–2024.8 Output growth in all of these sectors, except accommodation and food services, resulted mainly, or entirely, from gains in productivity rather than hours worked.9 Only in accommodation and food services did hours worked grow faster than productivity (although data for the comparison only go through 2022).10 Throughout the article, this case will be called “hours-driven growth,” in contrast to the “productivity-driven growth” of the other sectors.

| Description of sector | Output | Hours worked | Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 1.7 | -0.4 | 2.1 |

| Utilities | 1.2 | -0.6 | 1.8 |

| Manufacturing | 1.2 | -0.9 | 2.1 |

| Wholesale trade | 2.5 | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| Retail trade | 3.3 | 0.0 | 3.4 |

| Information (1) | 5.4 | 0.3 | 5.1 |

| Accommodation and food services (2) | 2.3 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Notes: (1) Data are only available through 2023. (2) Data are only available through 2022. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |||

In industries, the source of growth varied. Since there are so many industries for which BLS publishes data, it is helpful to limit the pool of the analysis. Chart 3 displays the industries from each of the sectors in chart 2, with the largest increases in annual real sectoral output quantities between 1990 and 2024.11 This narrows the list to industries that have contributed large amounts to national output growth over the last several decades. This means a lower bar of entry for some industries than others, consistent with the principle that sectoral output measures may understate the economic importance of goods-producing industries relative to some service-providing industries.12

| Industry | Output | Hours worked | Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil and gas extraction | 2.3 | -1.4 | 3.8 |

| Electric power | 1.5 | -0.8 | 2.3 |

| Motor vehicle manufacturing | 2.1 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| Commercial equipment wholesalers | 10.0 | 0.3 | 9.7 |

| Electronic shopping and mail-order houses | 14.4 | 2.8 | 11.3 |

| Software publishers | 12.8 | 5.5 | 6.9 |

| Restaurants and other eating places | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.8 |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |||

Where did these expanding industries’ output growth come from?13 As shown in chart 2, the most frequent growth pattern shown in chart 3 was productivity-driven. Commercial equipment wholesalers was a good example of this: trivial gains in annual hours worked but very fast growth in productivity. For software publishers (unlike its parent sector, information), there is a pattern of roughly equal rates of growth in productivity and hours worked. Throughout this article, this will be referred to as “balanced growth.” Finally, the restaurants and other eating places industry (like the accommodation and food services sector), demonstrates a largely hours-driven growth pattern.

To go further into each of these growth patterns, this article will highlight these three industries. Given the unique stories of these industries, this article will apply different lenses to look at the data for each industry.

The commercial equipment industry (NAICS 4234) comprises merchant wholesalers of equipment and supplies for various commercial and professional purposes. Among others, these include photographic, office, information technology, medical, dental, and ophthalmic products.

Chart 4 shows that output grew at double-digit percentage rates during the 1990–2000 and 2000–07 business cycles, before slowing down to a more moderate pace of growth after 2007. Productivity, which grew 9.7 percent per year over the full 1990–2024 reference period, was the engine of almost all gains in output (10.0 percent annually). Even from 2007 to 2019, after a much sharper slowdown in annual productivity growth (to 4.3 percent), the industry’s output growth came entirely from productivity growth. Since 2019, productivity growth has been negligible, meaning that output has risen almost in line with the moderate increase in annual hours worked.

| Period | Output | Hours worked | Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–2024 | 10.0 | 0.3 | 9.7 |

| 1990–2000 | 21.3 | 2.1 | 18.8 |

| 2000–07 | 11.2 | -2.4 | 13.9 |

| 2007–19 | 4.1 | -0.2 | 4.3 |

| 2019–24 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 0.1 |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |||

Some of the technological changes driving an acceleration in productivity growth from 1990–2000, especially after 1995, included the ongoing implementation of Electronic Data Interchanges and Universal Product Codes.14 The increasing use of these innovations helped enable the consolidation of wholesalers into larger firms, with increasing scale economies.15 These changes were all likely facilitated by an increasingly skilled workforce.16 The split by business cycles tells us that wholesale’s productivity growth from 2000–07 (3.3 percent annually) was not all that much lower than from 1990 to 2000 (4.1 percent). It seems reasonable to infer that technological developments underway in the 1990s had some lasting effects on the productivity of the sector into the 2000s. By 2007, perhaps, the productivity-enhancing benefits of various late 20th century wholesale industry transformations had already been largely absorbed. Productivity in the wholesale sector increased steadily, at 1.0 percent per year from 2007 to 2019 and 0.7 percent from 2019 to 2024.

A point to consider, in an industry with such diverse product lines as commercial equipment wholesaling, is whether shifts in the product mix might be reflected in the productivity statistics. In the years leading up to the 2007–09 Great Recession, most of the industry’s revenues came from the wholesaling of computers and peripheral equipment and software. (See chart 5.) However, after 2007, the share of sales in medical, dental, and hospital equipment and supplies has rapidly increased, while computers’ share of sales has fallen.17

| Year | Computers, peripheral equipment, and software | Medical, dental, and hospital equipment and supplies |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 57.2 | 19.8 |

| 2007 | 52.3 | 26.1 |

| 2012 | 46.7 | 32.8 |

| 2017 | 43.4 | 38.4 |

| 2022 | 43.1 | 39.8 |

| Source: Economic Census (2002-17) and Annual Wholesale Trade Survey (2022), U.S. Census Bureau. | ||

BLS source data are not quite detailed enough to enable us to compare the productivity of product lines within this industry. However, it may be instructive to look at related industries. Table 1 indicates impressive productivity growth from 1990–2007 in computer and peripheral equipment manufacturing, which supplied many of the products sold by commercial equipment wholesalers. The rapid productivity growth in the production of computer-related products may be related to the same pattern of growth in commercial equipment wholesalers. Likewise, the sharp slowdown in productivity growth after 2007 appears in both industries.

| Industry | Output | Hours worked | Productivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–2007 | 2007–24 | 1990–2007 | 2007–24 | 1990–2007 | 2007–24 | |

Computer and peripheral equipment manufacturing | 20.9 | -3.1 | -4.8 | -3.8 | 27.0 | 0.7 |

Medical equipment and supplies manufacturing | 4.5 | -0.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 3.8 | -0.8 |

Commercial equipment wholesalers | 17.0 | 3.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 16.8 | 3.0 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||

The story of computer and peripheral equipment manufacturing seems especially relevant in the broader context of productivity trends during and after the “Information Revolution.” Trends in industries such as this one had ripple effects across the economy. Productivity at the national level boomed during the late 1990s and early 2000s period of “computing and internet-related innovations.”18 Productivity then decelerated, starting around 2005. Many researchers accept that industries which “produce information technology (IT) or that use IT intensively” were central to both the productivity speedup and the slowdown.19 These industries included computer and electronics manufacturing, the retail sector, and—most pertinent to this article—wholesale.20

One final takeaway from table 1 is that the medical equipment and supplies manufacturing industry, which produced an increasingly large share of the products supplying commercial wholesalers, also had a productivity slowdown after 2007. In fact, it saw declining productivity from 2007 to 2024. As with the computer manufacturers, it is difficult to disentangle the effects of a supplier industry from the productivity trends of a wholesale industry “down the value chain.” Nonetheless, this relationship can be seen. The productivity trends of the commercial equipment wholesalers industry, both before and after 2007, are broadly consistent with both of its most related manufacturing industries and with the wholesale sector overall.

The software publishers industry (NAICS 511210) designs, develops, and publishes software. The two main categories of software products are “systems” and “applications.” Systems software helps your device run other programs; the operating system of your computer or smartphone is an example. Applications, or “apps,” are programs that a typical human user would access.21

Chart 6 reveals an astonishing growth rate of output from 1990 to 2000 (27.9 percent per year). While software publishers did not reach those heights of output growth in later periods, the annual rate over this article’s 1990–2024 reference period was still 12.8 percent.

| Period | Output | Hours worked | Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–2024 | 12.8 | 5.5 | 6.9 |

| 1990–2000 | 27.9 | 10.9 | 15.3 |

| 2000–07 | 4.0 | -1.5 | 5.6 |

| 2007–19 | 8.2 | 4.6 | 3.4 |

| 2019–24 | 8.9 | 7.3 | 1.5 |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |||

The growth pattern of software publishers looks balanced between hours worked and productivity at first glance. Both productivity and hours worked grew fast between 1990 and 2024. However, the split by business cycles shows that productivity outpaced hours worked in the 1990–2000 and 2000–07 periods; hours worked even declined in the second period. Then, annual hours worked rose faster than productivity in the 2007–19 period, accelerating further from 2019 to 2024, while productivity growth continued to slow down. Between these two periods, the pattern shifted: output growth came mainly from productivity growth up to 2007, but more from growth in hours worked after 2007. This occurred even though the growth rate of hours worked from 1990 to 2000 exceeded all of the subsequent business cycles.

A few notable changes to the software industry’s products have occurred during this article’s 1990–2024 period: One is the transition from purchased software to software-as-a-service (SAAS). This transition occurred largely between the 1990s and 2000s.22 Another development to note is the transition to smartphones after 2007. The BLS source data do not break down software products by desktop versus mobile devices. Nonetheless, data from Statista suggest that smartphone sales increased at an accelerating rate after 2007, as new devices broadened the appeal of the mobile format.23 Despite the proliferation of SAAS subscription models and smartphones, the industry has yet to see the growth rates of the 1990s again.

The software publishers industry also faced some structural disruptions. First, the dot-com bust of 2000, during which stocks of internet companies crashed, seems to have temporarily reversed the growing demand for software products. The relationship between the declining NASDAQ index and the “stifled demand for semiconductors and other IT-related goods” is well-known.24 However, the crash can also be seen in the services side of IT. Chart 7 indicates an abrupt deceleration in annual domestic capital investment in software after 2000. Growth recovered somewhat starting in 2003, but not to the towering rates of the late 1990s.

| Year | Percent change from previous year |

|---|---|

| 1990 | 8.2 |

| 1991 | 5.6 |

| 1992 | 6.1 |

| 1993 | 14.4 |

| 1994 | 7.7 |

| 1995 | 7.7 |

| 1996 | 14.9 |

| 1997 | 26.9 |

| 1998 | 18.6 |

| 1999 | 26.4 |

| 2000 | 13.1 |

| 2001 | 0.2 |

| 2002 | -4 |

| 2003 | 5.5 |

| 2004 | 10.8 |

| 2005 | 9.7 |

| 2006 | 6.6 |

| 2007 | 10.4 |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |

Finally, there is one more example of the enduring slowdowns from the mid-to-late 2000s involving users and producers of IT. Table 2 reveals a trend of decelerating output growth in most information sector industries after 2007 (radio and television broadcasting was the exception).25

| Industry | Output | Hours worked | Productivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–2007 | 2007–24 | 1990–2007 | 2007–24 | 1990–2007 | 2007–24 | |

Newspaper, periodical, book, and directory publishers | -0.6 | -4.9 | -1.4 | -6.1 | 0.8 | 1.3 |

Software publishers | 17.5 | 8.4 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 11.2 | 2.8 |

Radio and television broadcasting | 0.8 | 3.6 | 0.0 | -1.6 | 0.7 | 5.3 |

Cable and other subscription programming | 9.4 | 2.3 | 4.9 | -4.4 | 4.3 | 7.0 |

Wired telecommunications carriers | 3.6 | -1.2 | -0.8 | -2.6 | 4.4 | 1.4 |

Wireless telecommunications carriers except satellite | 24.0 | 6.7 | 11.2 | -5.3 | 11.4 | 12.6 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||

Yet, among these industries with decelerating output growth, software publishers stands out for the fact that productivity growth sharply decelerated, while robust growth in hours worked continued after 2007. The other information industries saw their quantities of work hours contract after 2007, while most maintained, or even increased, their productivity growth rates. The only exception was wired telecommunications, which saw its productivity decelerate, though not as much as in software publishers.

Chart 8 presents two different paths of industry-labor utilization at recent period-endpoint years. In 2007, workers at software publishers contributed 9.0 percent of the 5.6 billion hours worked in the information sector. By 2024, this climbed to 23.0 percent of the sector’s 5.4 billion hours worked.26 For comparison, the sectoral share of hours worked in wireless telecommunication carriers (except satellite) fell from 6.7 percent to 2.8 percent. This divergence in labor-hours trends stands in contrast to the output-growth trends, which were more similar between the industries. (See table 2.)

| Year | Total, information sector | Rest of information sector | Wireless carriers | Software publishers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 5,637.823 | 4,749.328 | 379.349 | 509.146 |

| 2019 | 5,335.384 | 4,275.385 | 184.267 | 875.732 |

| 2024 | 5,423.022 | 4,024.927 | 151.109 | 1,246.986 |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||

The restaurants and other eating places industry (NAICS 72251) contains establishments serving predominantly food and/or nonalcoholic beverages, in all their varieties. Chart 9 shows that hours worked in the restaurants industry grew faster than productivity in all three completed business cycles shown (1990–2019), thereby accounting for most of output growth. However, between 2019 and 2024, productivity rose by 3.3 percent per year. Here, even as work hours dropped (-0.4 percent), output increased by 2.9 percent. What happened to flip the growth pattern after three decades of consistent hours-driven growth?

| Period | Output | Hours worked | Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–2024 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.8 |

| 1990–2000 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| 2000–07 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 0.6 |

| 2007–19 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 0.3 |

| 2019–24 | 2.9 | -0.4 | 3.3 |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |||

Fortunately, more industry detail is available in the data. The BLS productivity program breaks out the restaurants and other eating places industry into two more detailed industries: full-service restaurants (722511) and limited-service eating places (a combination of NAICS 722513, 4, 5).27 As the industry titles suggest, the key difference is the type of service offered. If the customers are seated, look over a menu, and wait for a server to take their food or beverage order, then the establishment is probably full-service. Meanwhile, limited-service establishments may include fast-food, fast-casual, cafeterias, buffets, snack bars, and all other varieties of counter-service eateries and predominantly nonalcoholic drinking places.

Chart 10 breaks out the data for limited-service and full-service restaurants. The three completed business cycles from 1990 to 2019 look similar. Productivity grew slowly in both industries—a little more so in limited-service industries—as most of the growth in output came from increasing work hours.

| Period | Output | Hours worked | Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limited-service eating places | |||

| 1990–2000 | 2.1 | 2.2 | -0.1 |

| 2000–07 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 0.5 |

| 2007–19 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| 2019–24 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 2.1 |

| Full-service restaurants | |||

| 1990–2000 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 0.4 |

| 2000–07 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 0.6 |

| 2007–19 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 2019–24 | 3.6 | -1.1 | 4.7 |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |||

The 2019–24 trends, for both industries, look different from the preceding three decades: a productivity speed-up paired with a deceleration in hours worked. While the pace of output growth seems to have fully recovered from the pandemic crash in both industries, the growth accounting patterns changed. The fluctuations in the trends were more extreme in full-service restaurants. That industry saw hours worked decline in 2019–24, rather than merely slow down, and a somewhat stronger rate of productivity growth, compared to the limited-service industry.

Charts 11 and 12 dissect the latest business cycle, by year, for each of the restaurant industries.

| Year | Output | Hours worked | Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 100.000 | 100.000 | 100.000 |

| 2020 | 93.065 | 89.809 | 103.625 |

| 2021 | 103.832 | 96.228 | 107.903 |

| 2022 | 109.030 | 98.874 | 110.271 |

| 2023 | 111.767 | 101.416 | 110.205 |

| 2024 | 112.514 | 101.520 | 110.829 |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics | |||

The disruptions of 2020 reduced hours worked and output in both limited-service eating places (chart 11) and full-service restaurants (chart 12), but more severely in full-service restaurants. The recovery in 2021 in full-service restaurants was also stronger, aided by rapid growth in productivity. After 2021, annual productivity growth was moderate in both industries. Hours worked recovered more quickly in full-service restaurants, though from a lower base. The increases in output were correspondingly larger in this industry than in limited-service restaurants.

| Year | Output | Hours worked | Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 100.000 | 100.000 | 100.000 |

| 2020 | 74.494 | 73.357 | 101.550 |

| 2021 | 102.827 | 84.501 | 121.687 |

| 2022 | 111.505 | 92.591 | 120.428 |

| 2023 | 116.299 | 95.619 | 121.626 |

| 2024 | 119.404 | 94.815 | 125.932 |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |||

The reasons for the discrepancies between the industries in the current business cycle are unclear. The pandemic seems to have hastened the adoption of newer business practices and technologies in both restaurant industries, which could have boosted measured productivity in either industry. A survey from a trade association indicated that the shift to off-premises revenues accelerated during 2020 in all restaurant types.28 Later surveys confirmed that off-premises consumption in restaurants was still higher in 2021 than before the pandemic, concurrent with the drop in on-site dining.29 Even well after most pandemic restrictions loosened, off-premises dining remained higher in 2023 than in 2019 throughout the restaurant trade.30

Complementary to the increase in off-site consumption was the expanded use of digital technologies like ordering, payments, and delivery-management online or with mobile apps.31 Again, this does not seem to be merely a short-term reaction to pandemic conditions. Market survey data from 2023 suggest that many full-service restaurant operators introduced delivery service during the pandemic—including many fine-dining establishments—and that most of those who introduced it planned to retain it.32

One study demonstrated how an increase in off-premises dining can show up in the productivity statistics—specifically, in the limited-service restaurants industry.33 The researchers found evidence of a strong recovery in productivity based on analysis of proprietary microdata. They determined that productivity in limited-service restaurants rose “to a level some 15 percent higher than the pre-COVID steady state.”34 The strong recovery in the industry was attributed to the fact that customers spent less time indoors, especially due to an increase in takeout orders. The authors observed that the restaurants that increased takeout orders the most were the ones that increased productivity the most.35 The mechanism of increased productivity was a substitution of restaurant labor for home production. For example, takeout and delivery customers cleaned up their own tables and washed their own dishes.36

If these changes in customer behavior led to a substantial increase in the productivity of limited-service restaurants, it may be interesting to learn what a similar study would show for full-service restaurants. The post-2019 increase in off-premises dining was arguably a more radical change for full-service restaurants, where table service is a core attribute of the industry.

Since 1990, output growth at the macroeconomic level has come mostly from increases in productivity, rather than hours worked. Output growth decelerated from 2000 to 2007, and again from 2007 to 2019, but accelerated somewhat after 2019. Hours worked showed the most significant deceleration from 2000–07 and modest growth over the past two business cycles.

At the more detailed level, the picture varies. Among large industries with large output gains over the last 30 years, some industries have grown due to rapid gains in productivity, despite flat or declining hours worked. While this pattern is especially common, the commercial equipment wholesalers industry is a good example. Other industries have seen balanced growth from increases in both productivity and hours worked. Software publishers fits this description. Finally, some industries have grown from expansions in hours worked despite slow-growing or declining productivity. The restaurants and other eating places industry typifies this pattern.

Yet, for each of these three industries, the 2019–24 growth pattern was contrary to what came before. Change does not always happen in the same direction across industries. Low-productivity-growth industries become high-productivity-growth industries, and vice versa, even within the same national business cycle.

In the meantime, workers may shift from low-productivity industries to high-productivity industries, and vice versa, wherever the supply and demand for their skills converge. But, it is important to remember that any aggregate frame for measuring the economy is just the sum of more detailed sectors, industries, and workplaces—and their various patterns of growth.

Productivity, by definition, is the rate at which one hour of labor converts to a price-neutral unit of output, measured over time as an index. Stated in the way BLS measures it:

Implied in the definition is an equation of output as a multiple of hours worked and productivity:

.

Take the natural logarithms of each side and then differentiate with respect to time. With some substitution of terms and rearranging, equation (3) is created (shown here in dot notation), where Y is output, HW is hours worked, and LP is labor productivity:

.

This calculus equation can be rewritten in more general terms as equation (4), an approximation of the growth rate of output as the sum of contributions of the growth rates of productivity and hours worked:

.

The additive equation (4) is more accurate for smaller percentage changes. However, the multiplicative equation (2), as an identity, is always true. If the quantity of hours worked decreases without an increase in productivity, then output will also decrease.

Nathan Modica, "Industry growth patterns: a closer look at output, productivity, and hours worked from 1990 to 2024," Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 2025, https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2025.21

1 Economic growth (gross domestic product, or GDP) is often associated with improvements in the average material standard of living when it exceeds the rate of population growth (that is, increases in GDP per capita).

2 Statistically speaking, changes in labor productivity reflect the change in output that cannot be accounted for by a change in labor hours. Contributors to labor productivity include increases in the contribution of capital intensity (the capital-cost-share-weighted ratio of capital-to-labor inputs); the contribution of labor composition (via increasing education or worker experience); and contributors to total factor productivity (TFP), which include research and development (R&D), new technologies, economies of scale, managerial skill, and changes in the organization of production.

3 All U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) productivity program statistics presented in this article are on an annual basis. For example, the statement “hours worked increased” means that the quantity of work hours in year t + 1 was higher than in year t.

4 BLS productivity analysts compare points in time that cross complete business cycles. A fair period of analysis takes in the full course of expansion and contraction (or vice versa) that marks many large-scale economic phenomena. The framework of this article is annual data, so relevant peak-to-peak business cycles include 1990–2000, 2000–07, and 2007–19. Dating is based on output trends. (Note that the National Bureau of Economic Research is commonly cited as a source for dating business cycles on a quarterly or monthly basis. (See “U.S. business cycle expansions and contractions,” (National Bureau of Economic Research, last updated March 14, 2023), https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions.) In this article, NBER data are adapted to define business cycles for annual productivity data.

The period beginning in 2019 is an incomplete business cycle. Following the 2007–09 recession, economic growth occurred until the final quarter of 2019, or February 2020, depending on the period length used. Then, growth resumed after the short, sharp recession of 2020. The economic expansion continued through the last full year in this article’s analytical framework, 2024.

5 The BLS productivity program’s most widely referenced statistics are for the nonfarm business sector, for which annual output covers about 76 percent of GDP. For more information on BLS productivity concepts, see the productivity chapter of the Handbook of Methods (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics), https://www.bls.gov/productivity/handbook-of-methods.htm.

6 In this article, the term “annual percent change” refers to compound annual growth rate (CAGR).

7 For the classifications, history, and concepts of the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), see “North American Industry Classification System (NAICS)” (U.S. Census Bureau, last revised November 21, 2025), https://www.census.gov/naics/. In this Monthly Labor Review article, “industries” refers to 4-to-6-digit NAICS codes and “sectors” (mining, utilities, manufacturing, etc.) refers to 2-digit codes. Some industry names in this article have been abbreviated for readability. For example, NAICS 4234, “Professional and Commercial Equipment and Supplies Merchant Wholesalers” is abbreviated throughout this article as “commercial equipment wholesalers.”

8 Data for the manufacturing sector are found in the Major Sector Quarterly Labor Productivity and Costs databases. (See “Databases,” Office of Productivity and Technology (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics), https://www.bls.gov/productivity/data.htm.) For the information sector, the Major Sector and Major Industry Total Factor Productivity data were used. Statistics for all other 2-digit sectors in the table are available in the Detailed Industry Productivity databases. (See “Databases,” Office of Productivity and Technology (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics), https://www.bls.gov/productivity/data.htm.) Differences in source data and estimation methods are described in the productivity sections of the Handbook of Methods. (See Handbook of Methods (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics), https://www.bls.gov/productivity/handbook-of-methods.htm.

At the time of this article’s publication, data from the Major Sector Quarterly Labor Productivity and Costs and Detailed Industry Productivity databases were available through 2024. An exception is the accommodation and food services sector (hours worked were only available through 2024 and output and productivity were only available through 2022). Data from the Major Sector and Major Industry Total Factor Productivity release were available through 2023.

9 Sectoral output is the current-dollar value of goods and services produced by an industry for delivery to consumers outside that industry. Value-added output is the current-dollar value of output that has been adjusted for changes in inventory (gross output) and the removal of intermediate inputs (energy, material, and services). See the “Productivity glossary” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics), https://www.bls.gov/productivity/glossary.htm. Sectoral output measurements for NAICS industries (including the 2-digit sectors in chart 2) are not additive to the nonfarm business sector level (i.e., national, macroeconomic measures) because intermediate inputs for one industry are outputs for another industry. Thus, sectoral output measurements for all industries added together would entail double-counting economic activity.

10 In the mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction sector, in the 2000−07 business cycle, the annual percent change of hours worked (4.1) far exceeded productivity (-4.7). In the utilities sector, from 2007 to 2019, hours worked increased at the same annual rate as productivity, 0.1 percent. However, only in the accommodation and food services sector did the annual percent change in hours worked exceed that of productivity over the long term. (BLS data for this sector cover 1990 to 2022.)

11 The industries are selected by their increases in the quantity of real annual sectoral output (2017 constant dollars), rather than the growth rate, to highlight industries contributing a large amount to national growth (that is, large weights in aggregate growth). BLS productivity programs use 2017 as the base year. Note that the deflators for these industry calculations are a unique composite of weighted price indexes for each industry.

| Sector | Industry (NAICS) | 1990 | 2024 | 1990−2024 change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Mining | Oil and gas extraction (2111) | 161,629.075 | 352,742.186 | 191,113.111 |

Utilities | Electric power (2211) | 271,664.134 | 451,836.140 | 180,172.006 |

Manufacturing | Motor vehicle manufacturing (3361) | 183,493.514 | 367,897.085 | 184,403.571 |

Wholesale | Commercial equipment wholesalers (4234) | 22,218.234 | 565,417.503 | 543,199.269 |

Retail | Electronic shopping and mail-order houses (454110) | 13,035.192 | 1,280,840.586 | 1,267,805.394 |

Information | Software publishers (511210) | 8,101.840 | 492,456.460 | 484,354.620 |

Accommodation and food services | Restaurants and other eating places (72251) | 332,496.221 | 738,407.219 | 405,910.998 |

Note: NAICS = North American Industry Classification System. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||

12 It is not straightforward to compare the economic importance of sectoral output levels in goods-producing industries, such as manufacturing, to service-providing industries, such as retail services. Manufacturing industries (and mining and utilities) produce a tangible output. Defining the output of service industries is more difficult. For example, in retail industries, the value of real sectoral output is measured as total sales revenue deflated by the prices of products sold outside the industry. Thus, retail sales values reflect the entire value chain of the product sold, from product design to delivery to the final consumer. Please see a further explanation in the BLS article “Sectoral versus gross margin: alternative measures of output and labor productivity for retail industries” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, last modified May 21, 2025), https://www.bls.gov/productivity/articles-and-research/retail-transformation-measures/retail-trade-margin-productivity/home.htm.

13 Throughout the article, “Output” refers to an indexed value of real sectoral output, that is, constant-dollar quantities of output produced by an industry.

14 Christopher Kask, David Kiernan, and Brian Friedman, “Labor productivity growth in wholesale trade, 1990–2000,” Monthly Labor Review (December 2002), p. 5, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2002/12/art1full.pdf.

15 Ibid., p. 6.

16 Ibid., pp. 3−4.

17 The BLS source data do not specify how many of the work hours or jobs were allocated to particular product lines.

18 Shawn Sprague, "The U.S. productivity slowdown: an economy-wide and industry-level analysis," Monthly Labor Review (April 2021), https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2021.4.

19 The phrase in quotes comes from John G. Fernald, “Productivity and potential output before, during, and after the Great Recession,” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 29, no. 1 (January 2015), pp. 1–51, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/680580, p. 1. However, the centrality of IT-using or -producing industries to the story of productivity speedup and slowdown in the 1990s and 2000s is noted by many researchers.

20 Ibid. In addition to Fernald, “Productivity and potential output before, during, and after the Great Recession,” for an overview of the literature, as well as further analysis, see also the section “Industry contributions to the MFP slowdown” in Sprague, "The U.S. productivity slowdown: an economy-wide and industry-level analysis."

21 According to the Economic Census 2017, systems software included (but was not limited to) operating systems software, network software, database management software, and development tools and programming languages software. Defined applications software types included general business productivity and home use applications, game software, cross-industry application software, vertical market application software, and utilities software. (See item 22 in the survey form “IN-51121 - Software publishing,” 2017 Economic Census (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017), https://bhs.econ.census.gov/ombpdfs/export/IN-51121_su.pdf.)

22 Martin Campbell-Kelly and Daniel D. Garcia-Swartz, “From products to services: the software industry in the internet era,” The Business History Review 81, no. 4 (Winter, 2007), pp. 735−764, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25097422.

23 See the proprietary chart from Statista: “Number of smartphones sold to end users worldwide from 2007 to 2023” (Statista, January 2023), https://www.statista.com/statistics/263437/global-smartphone-sales-to-end-users-since-2007/. Note also that, according to the Computer World article “Evolution of Apple’s iPhone,” Apple’s iPhone was released in 2007 (although other companies launched and improved products around the same time). (See Ken Mingis and April Montgomery, “Evolution of Apple’s iPhone,” Computer World (September 20, 2024), https://www.computerworld.com/article/1622162/evolution-of-apple-iphone.html.)

24 In Langdon et al., “U.S. labor market in 2001,” the relationship between stock prices and demand for semiconductors was described as follows: “As stock valuations fell, investor interest in internet ventures waned, and the ventures’ falling liquidity stifled demand for semiconductors and other IT-related goods.” See David S. Langdon, Terence M. McMenamin, and Thomas J. Krolik, “U.S. labor market in 2001: economy enters a recession,” Monthly Labor Review (February 2002), pp. 3–33, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2002/02/art1full.pdf, p. 9.

25 These industries do not represent the full scope of the information sector. Rather, they were chosen for the table because the BLS productivity program publishes productivity measures for all of them.

26 Data for the information sector in 2024 were not available from the Major Sector and Major Industry Total Factor Productivity database at the time of this article’s publication. Instead, this article uses the sum of hours worked in the 3-digit information industries: NAICS 511, 512, 515, 517, 518, and 519. This sum may differ slightly from the sectoral figure in the Major Industry release for comparable reference years due to differences of source data vintages or slight differences of methods.

27 Source data limitations prevent the publication of distinct productivity and related measures for NAICS 722513, 722514, and 722515.

28 See Hudson Riehle, Bruce Grindy, Beth Lorenzini, Susan Raynor, and Dani Smith, “Off-premises sales take over,” in State of the restaurant industry 2021 (National Restaurant Association (NRA), January 2021), p. 14, https://go.restaurant.org/rs/078-ZLA-461/images/2021-State-of-the-Restaurant-Industry.pdf. The chart portrays data from the NRA’s Restaurant Trends Survey, December 2020.

29 See the chart, “Off-prem versus on-prem,” in Hudson Riehle, Bruce Grindy, Beth Lorenzini, Susan Raynor, and Dani Smith, State of the restaurant industry 2021 mid-year update (National Restaurant Association, August 2021), p. 14, https://go.restaurant.org/rs/078-ZLA-461/images/2021-SOI_Mid-Year%20Update%20Final.pdf. The chart summarizes data from the Consumer Restaurant Frequency Survey comparing changes in off-site and on-site dining for three meal categories between March 2020 and “early August 2021.”

See also “Off-premises overview” in Hudson Riehle, Bruce Grindy, Beth Lorenzini, Susan Raynor, and Daniela Smith, State of the restaurant industry 2022 (National Restaurant Association, December 31, 2022) p. 26, https://xchange.avixa.org/documents/pdf-report-2022-state-of-restaurant-industry. The chart, based on the Restaurant Trends Survey data from November 2021, indicates that “restaurant operators across all 6 major [restaurant industry] segments said off-premises dining [still] represented a higher proportion of their average daily sales than it did before the pandemic.”

30 See Hudson Riehle, Bruce Grindy, Beth Lorenzini, Helen Jane Hearn, and Daniela Smith, State of the restaurant industry 2024 (National Restaurant Association, 2024), p. 28, https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.krha.org/resource/resmgr/2024-State-of-the-Restaurant.pdf. “Forty-nine percent of all restaurants (43 percent of full-service and 55 percent of limited-service) say off-premises business represented a higher proportion of sales in 2023 than it did in 2019. Only 22 percent say it made up a smaller portion of total sales.”

31 Riehle, Grindy, Lorenzini, Raynor, and Smith, State of the restaurant industry 2021, pp. 21–23.

32 Hudson Riehle, Bruce Grindy, Beth Lorenzini, Helen Jane Hearn, and Daniela Smith, State of the restaurant industry 2023 (National Restaurant Association, 2024), p. 26, https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.krha.org/resource/resmgr/nra_/2023-State-of-the-Restaurant.pdf.

33 Austan Goolsbee, Chad Syverson, Rebecca Goldgof, and Joe Tatarka, “The curious surge of productivity in U.S. restaurants,” NBER Working Paper 33555 (National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2025), https://doi.org/10.3386/w33555. The article was also published by the Becker Friedman Institute as a working paper. See Austan Goolsbee, Chad Syverson, Rebecca Goldgof, and Joe Tatarka, “The curious surge of productivity in U.S. restaurants,” Working Paper No. 2025−39 (Becker Friedman Institute of Economics, March 2025), https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/BFI_WP_2025-39.pdf.

34 Ibid., p. 1.

35 Ibid., pp. 10−12.

36 Ibid., p. 9.